If you flew 9,000 miles east from Florida’s sand spit Cape Canaveral, you would arrive at the land of the sky: the vast steppes of Kazakhstan, a flat plain where the yellowed grasslands turn green only in the spring — where at day's end one can see nothing, not even a leaf or twig, between self and setting sun.

It was this bare, unpopulated land that was chosen in the 1950s by a small army of Russian space pioneers, scientists, rocket engineers and technicians, laborers and cooks and carpenters and masons to build the great Soviet Baikonur Cosmodrome — a sprawling space center located perfectly to launch rockets and land spacecraft where mishaps would do little damage to the sparse flora and fauna. Even more importantly, the desolation would keep secrets hidden.

They developed and tested rockets, and placed Earth’s first artificial satellite in orbit on Oct. 4, 1957. Then, on the morning of April 12, 1961, they gathered around a large rocket with a man sitting inside a spacecraft mounted on its top.

Soon came the countdown phase the man had been waiting for.

"Gotovnosty dyesyat minut."

Yuri Gagarin felt motors whining. Excellent. He knew what the sounds meant.

The final seconds rushed away; a voice cried, "Zazhiganiye!"

Gagarin needed no words to tell him he had ignition, as powerful main thrust chambers and smaller control engines lit up in an explosive fury of 900,000 pounds of thrust. The mighty rockets strained, explosive hold-down bolts fired, and the first man to leave Earth was on his way.

It was 9:07 a.m. on the steppes of Kazakhstan, 1:07 a.m. in New York. America slept, unaware of Yuri Gagarin’s jubilant cry, "Off we go," from his climbing rocket, bringing smiles and grins to the crews in Baikonur's launch control center. As soon as the big rocket cleared its launch gantry, many members of the launch team whose duties were finished rushed outside to see the rocket accelerating faster and faster. Binoculars showed them a dazzling ball of fame rising with increasing speed.

In just those first few minutes of ascent, Yuri Gagarin was traveling faster than any man in history. Then, the booster was bending far above and away over the distant horizon, leaving behind a twisting trail of condensation as a signature of its passage.

Through the increasing forces of heavier and heavier acceleration, Gagarin maintained steady reports. He was young and muscular, and he absorbed the punishment easily.

Gagarin heard and felt a sudden loud report, then a series of bumps and bangs as the protective shroud covering his Vostok spacecraft was hurled away by small rockets. Now he could see clearly through his portholes a brilliant horizon and a universe of blackness above. Finally the central core exhausted its fuel, and explosive bolts fired to release the final "half-stage" rocket to complete the burn to orbital height and speed.

The miracle was at hand. A human was orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles an hour. Gagarin, in a spaceship he named Swallow, had entered orbit with a low point above Earth of 112.4 miles, soaring as high as 203 miles before starting down again.

Those on the ground listened in wonder at Gagarin’s smooth control, his reports of what he was feeling, and how his equipment was working. Then he went silent for several moments as a never-before-known sensation enveloped his body and his mind.

He felt as if he were a stranger in his own body. He was not sitting or lying down. Up and down no longer existed. He was suspended in physical limbo, kept from floating about loosely only by the harness that strapped him to his contoured couch. About him, the magic of weightlessness appeared in the form of papers, a pencil, his notebook and other objects drifting, responding to the gentle tugs of air from the fans of his life-support system.

He forced himself back to his schedule, reporting the readings of his instruments. As critical as those reports were, there was even greater interest in what Gagarin felt and saw. He told those in ground control that weightlessness was "relaxing." He took precious moments as he orbited the earth, covering five miles every second, to report, “The sky looks very, very dark and the earth is bluish.” He waxed enthusiastic about the startling brightness of Earth's sunlit side. He raced through a sunset and a sunrise, and almost before he realized the passage of time, he was nearing the end of man’s first orbital flight.

He would use his manual controls only in an emergency. Now he remained both physically relaxed and mentally vigilant as he monitored the automatic systems turning his spacecraft about for retrofire.

Rockets blazed. The sudden deceleration rammed him hard into his couch. He smiled with the full-body blow; everything was working perfectly.

It may have taken those a century ago 88 days, but he had circled the globe in 89 minutes.

As he plunged across east Africa, he began his return to Earth, flying backward.

He knew he was feeling the first caress of weight from deceleration as his spaceship arched downward into the thickening atmosphere. Now he was a passenger within a blazing sphere. Through the portholes he saw flames, at first filmy, then becoming intense blazing fire as friction from the atmosphere heated the ablative covering of his spacecraft to thousands of degrees. The protective coating burned away with increasing fury. He was in the center of a man-made comet streaking toward the flattening horizon. Though inside a fireball, he was cool and comfortable.

Then he was through re-entry burn. His ship slowed to subsonic speed. Twenty-three thousand feet above the ground, the escape hatch blew away. Gagarin saw blue sky, a flash of white clouds. Small rockets within the spacecraft fired, sending the cosmonaut and his contour couch flying away.

Yuri watched a stabilization chute billow upward. Everything worked perfectly. For 10,000 feet he rode downward in his seat. In the near distance he saw the village of Smelovaka.

Thirteen thousand feet above the ground, he separated from the ejection seat and deployed his personal parachute. He breathed in deeply the fresh spring air. What a marvelous ride down!

On the ground, two startled peasants working in a field with their cow watched as Gagarin, wearing a bright orange suit topped with a white helmet, drifted out of the sky. Yuri hit the ground running. He tumbled, rolled over and immediately regained his feet to gather his parachute. Gagarin unhooked the parachute harness and looked up to see a woman and a girl staring at him.

"Have you come from outer space?" asked the astonished woman.

"Yes, yes, would you believe it?" Yuri answered with a wide grin. "I certainly have."

---

Three weeks later, Astronaut Alan Shepard would make America’s first trip into space, and a decade later, with his partner Edgar Mitchell, he would take the longest walk — two miles — on the moon. The next installment of the "Moon Shot" story focuses on Shepard's story.

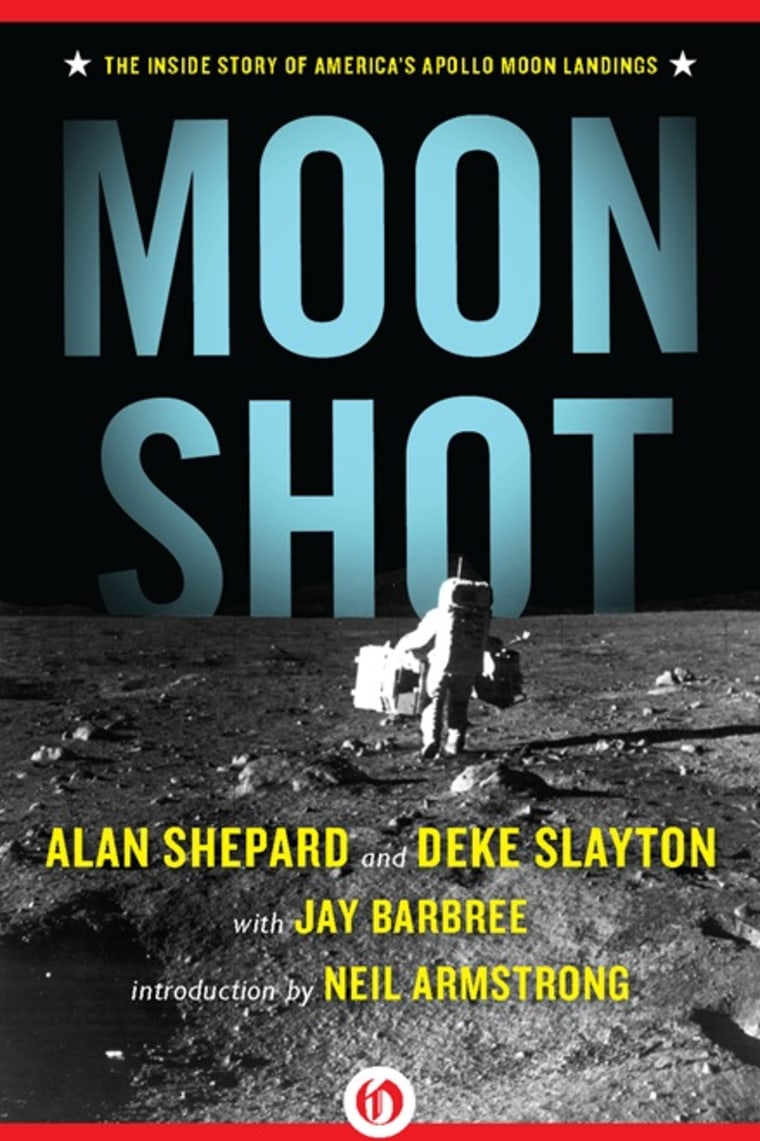

Excerpted from "Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings," by Alan Shepard and Deke Slayton with Jay Barbree. Reprinted with permission. 50th-anniversary enhanced e-book edition published by Open Road Integrated Media, copyright 2011. Available on May 2 via Apple iBookstore, BarnesandNoble.com, Amazon.com, Sony Reader Store and Kobo Books.