Ocean chemist Peter Brewer looks at the map on his laptop computer, jealous of what his terrestrial peers have been allowed to do around the globe. Dozens of red dots show where scientists have tested how increases in a gas tied to global warming affect land ecosystems.

Brewer is still waiting for a first red dot under the seas. For all the tests on land, not a single large-scale test has been sanctioned to simulate what the oceans of the late 21st century might look like if emissions of carbon dioxide, or CO2, continue to rise.

This, despite estimates that the oceans have already absorbed 400 billion tons of CO2 from fossil fuels and continue to take in 21 million tons a day -- emissions that many scientists fear are warming the Earth beyond its natural course.

Granted, the oceans are huge carbon reservoirs, naturally holding an estimated 139,000 billion tons of CO2, but what's not known is how much variation is enough to throw the system out of whack.

"The problem," Brewer says, "is that about 50 percent of the 400 billion tons of CO2 we have put in the ocean is in the upper 200 meters. Since the average depth of the ocean is 4,000 meters, we are having a large impact on the shallow surface layers where most marine life is."

Fear of 'unknown territory'

That's not to say Brewer hasn't done some limited testing himself. The senior scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California, he started with a humble beaker and moved up to 20 liters, seeing how a bit of C02 in a specific spot under water changed the chemistry.

But the process of getting wider acceptance for his research has been frustrating.

"For 20 liters of CO2 we needed a permit," he notes. "Our ship let that much out in four minutes!"

On top of that, he says, "it took us six weeks of intense negotiations" with officials at the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, where the test took place.

"It's because of unknown territory," says Brewer. People hear carbon dioxide and immediately alarm bells go off. But he also understands. "It's as if someone came up to you and asked if they could use your backyard."

Why bother?

Brewer's chief concern is the fact that adding C02 to the ocean increases its acidity, or pH level. "There is quite a range of pH" in the seas, he notes, and while many marine animals can migrate through such ranges, many are finely attuned to their pH environment and can't tolerate significant variations.

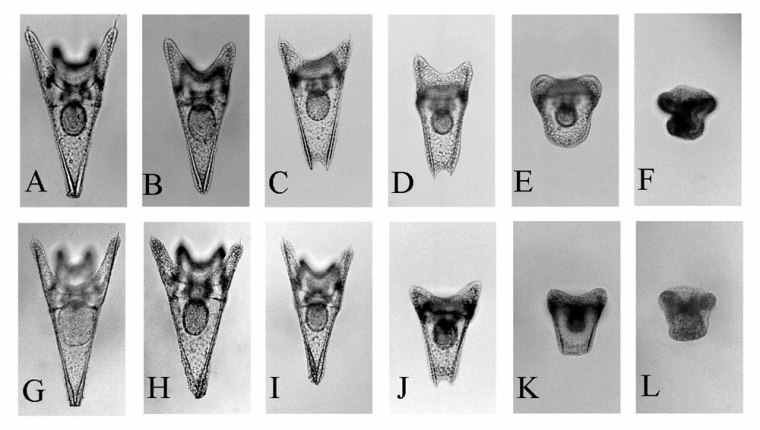

Brewer points to lab research by Yoshihisa Shirayama, a marine biologist at Kyoto University in Japan, who found significant changes in sea urchin development when CO2 was introduced and changed pH levels.

Chris Field, a Carnegie Institution global ecology researcher at Stanford University, agrees with the pH concerns and notes that acidity is particularly hard on coral reefs. "The effects of ocean CO2 are likely to be mainly on pH," he says, "which alters things like calcification in corals and other organisms with carbonate skeletons."

Brewer sees the pH changes as "an additional insult" on top of other effects of C02 -- in particular, warmer sea temperatures, which are hardest on coral reefs.

pH past, and future?

Brewer has estimated that the surface pH of oceans worldwide is 0.1 units lower than in pre-industrial times.

The pH concerns led to computer modeling by Livermore National Lab researchers Ken Caldeira and Michael Wickett. In a 2003 report in the journal Nature, they found no evidence that ocean pH was ever more than 0.6 units lower than today.

A drop of 0.7 units is possible, they said, warning that "unabated CO2 emissions over the coming centuries may produce changes in ocean pH that are greater than any experienced in the past 300 million years."

That report just looked at pH levels from airborne CO2 emissions that fall into the seas. But oceans could see much more if another idea takes hold: pumping C02 emissions from power plants directly into the waters.

The idea is to trap it there instead of sending it into the atmosphere, where it could be altering global temperatures.

Trees and grasses, which naturally absorb C02 as well, have also been eyed as traps, or sinks, but recent research suggests their contribution will be limited. That's raised the profile of ocean trapping even higher, but it's also been on Brewer's mind.

Next steps

Brewer doesn't claim to know how much additional CO2 marine life can tolerate, but he thinks long-term tests will determine that and he took his passion and his plea to the recent annual conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

"It's the only way to find out how coral reefs, deep-sea fisheries and other marine environments will react to a change in ocean pH," he told reporters and peers in Seattle. "You have to do the experiment."

He's hoping that now, six years after his first beaker test, he can get support for a much grander experiment: a patch of ocean that's marked off with sensors capable of tracking CO2 as it disperses through that area. Brewer figures a good place to start is by a coral reef.

Testing could be five years out still, and Brewer recognizes the challenge of dealing with a test site where the ecosystem moves around with the tides. "Researchers on land have it easy since trees don't move," he notes.

Stanford's Field sympathizes with Brewer, noting that a key obstacle has been how "technically difficult" the research is. "He is one of only a few people who could do this," Field says.

Still, Field thinks science can make room for ocean studies. "I don't think it is a question of whether land or ocean studies are more important," says Field, author of the new book "The Global Carbon Cycle." "But we should do at least a few ocean studies to get a sense of the range of possible effects."

Brewer's earlier, limited tests were funded by the U.S. Energy Department and Japan, and he's confident money wouldn't be an obstacle. What he instead worries about is more frustration in trying to get a test permit.

"Cost is not an issue, it's attitude," he says. When it comes to grasping what's at stake, "there's a very large public gap."