By gazing at the edges of sunspots, astronomers now are pinpointing key details of how these mysterious dark marks form.

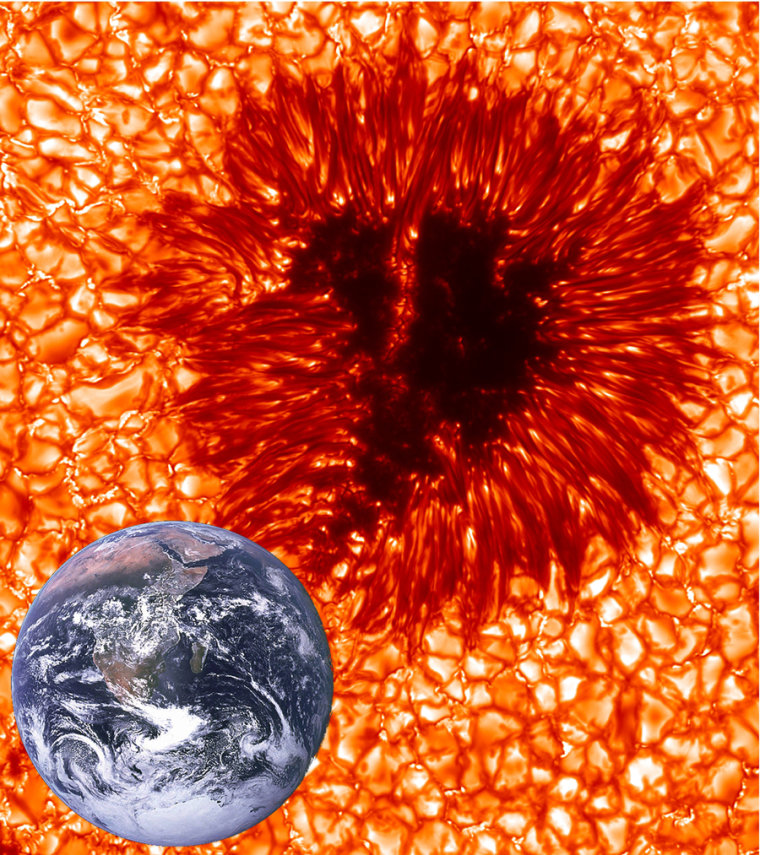

Sunspots are blotches on the sun that appear dark because they are cooler than the rest of the solar surface.

Astronomers do know they are linked to intense magnetic activity on the sun, which can suppress the flow of hot matter, but much about their structure and behavior remains enigmatic.

The dark heart of a sunspot, called the umbra, is surrounded by a brighter edge known as the penumbra, which is made of numerous dark and light filaments more than 1,200 miles long.

They are relatively thin, at about 90 miles in width, making it difficult to resolve details that could reveal how they arise.

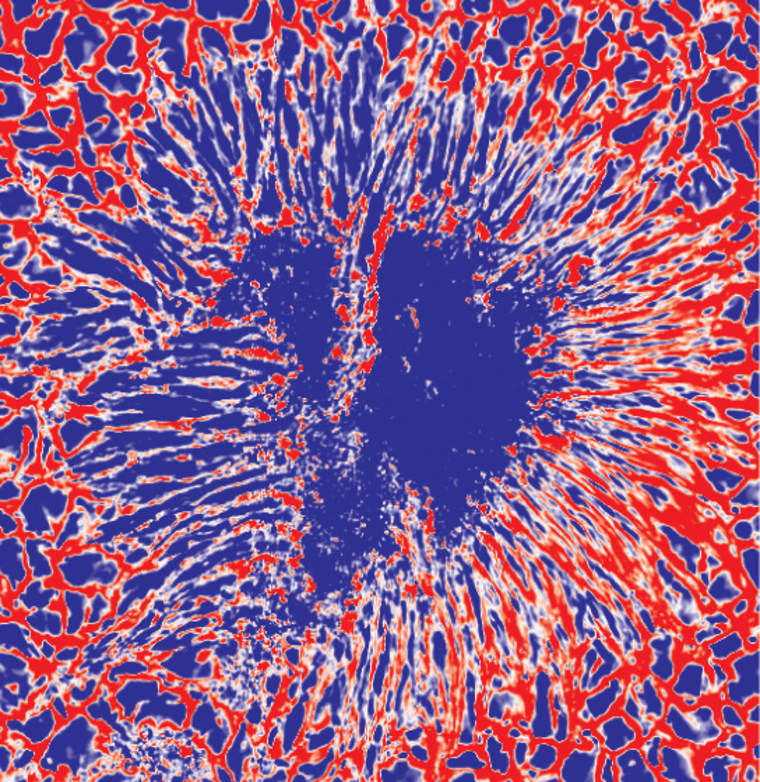

Now scientists have discovered these columns are rapid downflows and upflows of gas, matching recent theoretical models and computer simulations suggesting these filaments are generated by the movement of hot and cold gases known as convective flow.

The researchers used the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope to focus on a sunspot on May 23, 2010.

They found dark downflows of more than 2,200 miles per hour and bright upflows of more than 6,600 miles per hour. The models suggest that columns of hot gas rise up from the interior of the sunspot, widen, cool and then sink downward while rapidly flowing outward.

"This is what we have been expecting to find, but we were maybe surprised about actually succeeding in seeing these flows," researcher Göran Scharmer, a solar physicist at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Stockholm University in Sweden, told Space.com.

In the future, the researchers hope to also measure the magnetic fields linked with these flows to learn more about how they cause such activity.

The scientists detailed their findings in a paper published online June 2 in the journal Science.