June has been declared National Oceans Month, via a writ from the White House a few days ago, and this week communities around the planet will mark World Oceans Day.

The flurry of recognition seems appropriate for a region that covers 70 percent of the Earth's surface and provides about half the air we breathe, courtesy of the microscopic, oxygen-producing phytoplankton floating in it.

Yet much about the planet's oceans remains a mystery. As of the year 2000, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that as much as 95 percent of the world's oceans and 99 percent of the ocean floor are unexplored.

Exploring these regions deep below the ocean's surface is difficult, time-consuming and expensive. Which hasn't stopped people from trying — and making incredible discoveries along the way.

Known unknowns

Shallower parts of the ocean, and those closer to coastline, have understandably gotten the lion's share of investigation.

What's been fairly well explored is about one Washington Monument down into the ocean — about 556 feet — said Mike Vecchione, a veteran scientist with NOAA and the Smithsonian Institution.

Impressive, perhaps, yet the average depth of the planet's oceans is 13,120 feet, the height of many peaks in the Rockies and the Alps.

"In the deep ocean we're still exploring, and frankly, that's most of the planet that we live on. And we're still in the exploratory phase," Vecchione told OurAmazingPlanet.

Although hard numbers are difficult to pin down, the ocean possesses more than 90 percent of the living space on the planet, perhaps as much as 99 percent, Vecchione said — which means that landlubbers like humans or parakeets or armadillos are rare exceptions in a world of ocean dwellers.

Deep sea discoveries

Humans are familiar with all sorts of coastal ocean creatures (from crabs to seaweed), coral reef denizens (from clownfish to coral itself), and the bigger, charismatic fauna of the sea (dolphins and whales). But the picture of a whole strange world of life in the deep, dark waters of the world's oceans is slowly emerging.

"People used to think that biodiversity dropped off as you got deeper and deeper in the ocean, but that was just because it's harder and harder to catch things as you get deeper," said Ron O'Dor, a professor at Dalhousie University in Canada, and one of the senior scientists for the Census of Marine Life, a decade-long international study of the planet's oceans that uncovered more than 1,200 new species, excluding microbes, since the project began in 2000.

Seafaring robots are fueling some of that discovery. Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), which are tethered to ships, and more recently, Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), which roam freely, collecting visuals and samples during jaunts dictated by computer programs, have made exploration more efficient, O'Dor said.

However, O'Dor told OurAmazingPlanet, even the best robots can't totally replace humans.

Pictures on computer screens are great, "but that's still not the same as having somebody come back from the deep sea and having them describe it to you," O'Dor said.

Humans in the depths

Vechionne can do just that. In 2003, he was one of the first humans to descend into one of the deepest spots on Earth, the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone, a gash in the mid-Atlantic seafloor that is 14,760 feet at its deepest.

During the dive he spied something out of the corner of his eye — a dumbo octopus.

"I was able to tell the pilot to turn around, and we got some really great video," Vechionne said, something that wouldn't have happened without humans aboard.

Although he witnessed the wonders of the deep sea firsthand, Vechionne said it's important to use all the tools available for exploration, because much is lurking out of sight in the darkness. A new species of squid, for example.

Vechhione pointed to the discovery of the bigfin squid about 10 years ago, a pale, leggy creature that can reach up to 21 feet in length and would look right at home in a 1960s B-movie.

"It was exciting when we first discovered them," Vechionne said. "I was jumping up and down in my office."

The squid were caught on film, thanks to ROVs. And if such huge creatures eluded discovery until recently, both Vechhione and O'Dor said, what else is out there?

Yet sending anything to the ocean depths, human or machine, is expensive, and both scientists said funding is a constant issue.

Private sector dives?

Enter British tycoon Richard Branson, who announced plans earlier this year to send humans, aboard newfangled submersibles, to the five deepest spots on Earth.

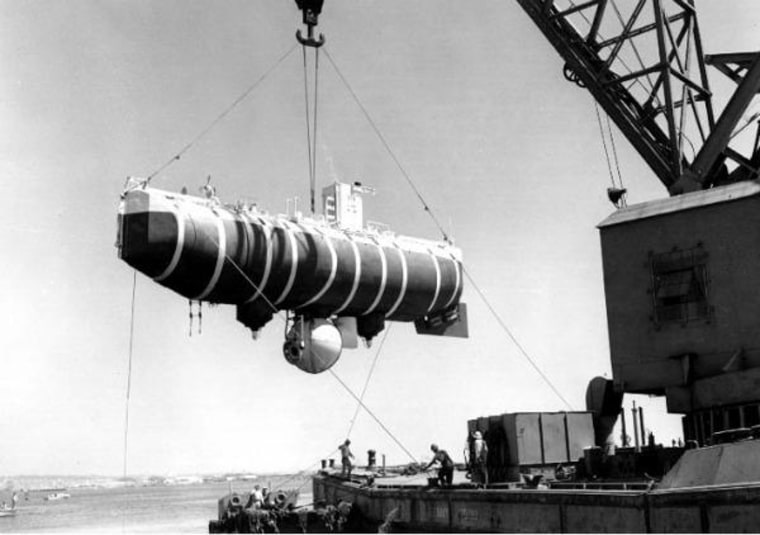

The deepest is the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean, an eye-popping 36,200 feet below the surface — more than a mile deeper than Mount Everest is tall. Humans have visited this trench only once, in 1960, when the Trieste, a deep-diving craft purchased by the U.S. Navy, spent about 20 minutes parked on the ocean floor.

The two humans aboard the Trieste were U.S. Navy Lt. Don Walsh and Swiss scientist Jacques Piccard, co-designer of the remarkable vessel. To this day, their dive has been unmatched.

More humans, 12 in all, have walked on the moon than have traveled to the deepest parts of our own planet.

O'Dor said discovery is important for its own sake, but humans have a vested interest in what is happening to the oceans we depend on for air, food and transport, among other things.

"Not only is there a lot out there left to discover, but there's a lot that's changing, and we need to more or less routinely keep track of those changes," O'Dor said. "To quantify and document them."