Alternative vehicles are still "alternative" in part because fuel cell and battery technologies still have many hills to climb — cost, efficiency and weight to name a few. A group of MIT researchers thinks they can pave the way. They recently combined the strongest aspects of traditional batteries and fuel cells to create a whole new kind of battery.

"It's a flowing electrode that's electrically conductive all of the time. That's the secret sauce," said Yet-Ming Chiang, the professor of material science and engineering at MIT who led the development. His interdisciplinary team included researchers Mihai Duduta, Bryan Ho, Pimpa Limthongkul, Vanessa Wood, Victor Brunini, MIT professors Craig Carter, Angela Belcher, Paula Hammond, and Rutgers University professor Glenn Amatucci.

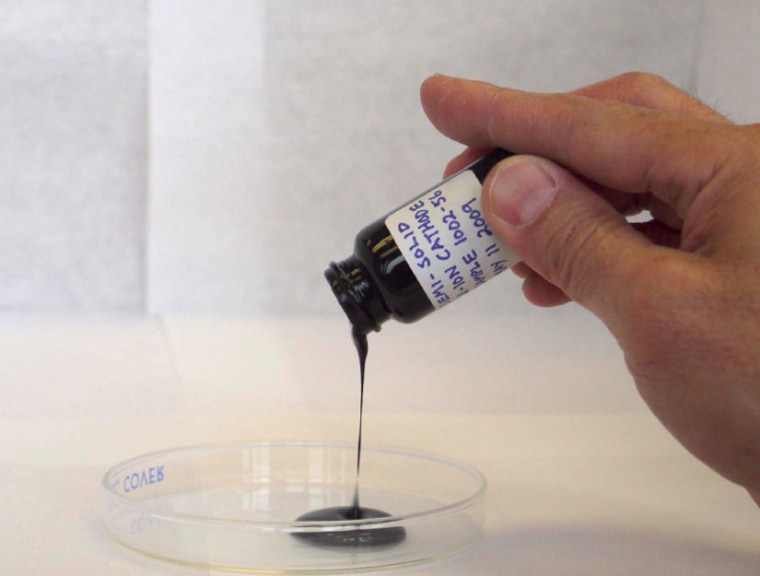

The battery is similar to flow batteries that have been in existence for decades. However, unlike the low-energy batteries of the past, the new battery has a semi-solid flow system that relies on the flow of a concentrated energy-dense suspension of particles dubbed "Cambridge crude." Another key difference is that the battery separates the reactor from the reactants.

This goo system has several advantages over fuel cell and regular lithium-ion battery technology, Chiang said. For one, it allows a larger percentage of the battery to store energy. "We can go directly from the electrodes and entirely bypass the cell-making part," he said.

Chiang also expects their battery will lower costs because its structure is simpler to manufacture and reduces the expensive components that don't carry energy. "We can produce the flowing electrodes in a mixing operation and then simply use them to fill a device that's basically bolted together," he said.

The electro-chemical fuel can be reused so drivers could feasibly swap out a spent tank for one that's been charged. Since the batteries decouple energy and power, fueling stations could offer different types of electro-chemical fuel.

"If you would like high-power fuel, we could give you high-power fuel. If you would like longer-range fuel: 'premium range,'" Chiang said. This would give drivers the ability to get electro-chemical fuel tailored to their operating conditions — as well as the season. Electrolyte chemists usually design for the broadest range of temperatures, giving up performance at the high and low ends.

"The sweet spot we're aiming for is a battery with enough power for any vehicle application but with the longest run-time possible," Chiang said.

Dan Steingart is an assistant professor in chemical engineering at the City College of New York who works on developing batteries for grid-scale applications.

"This battery is a sort of a hybrid of the best parts of a traditional battery and a fuel cell," he said of the semi-solid flow battery design. Being able to recharge the waste stream is one of the main advantages, he added. "It's as if you had a way of capturing the carbon and water and turning it back into gasoline at the gas station."

But Steingart cautions that significant challenges remain. Making sure the slurry flows reliably without clogging lines is going to be one of them, he said. Another will be getting the "Cambridge crude" in and out of the battery safely, and then scaling that up.

"How do you come up with a plumbing solution to get around that?" he asked. "That will make these guys a lot of money, or ultimately sink them."

Chiang and 24M Technologies aim to have a first commercial prototype ready within two years and, if all goes well, the first commercial systems could be in production during the later part of this decade.

"People talk about 'range anxiety,'" Chiang said. "Our goal is to provide 'range euphoria.'"