Apollo 8 was the first flight to take humans beyond the grip of Earth’s gravity. During the Christmas season of 1968, astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell and Bill Anders flew to the moon, entering orbit around its cratered surface and then safely returning to their native planet. They did not land on the lunar surface, but they did beat a Russian spaceship named Zond into an orbit around the moon. Their flight was a necessary prelude to landing astronauts on the celestial body closest to Earth. The complete story is in Alan Shepard and Deke Slayton’s book, "Moon Shot." Here’s an excerpt:

Behind the mass of the moon, it was as if Apollo 8 and its three men did not exist. There was no way to communicate with the spacecraft. No telemetry signals could be received. The mission had gone quiet.

As the precise moment dictated by its flight plan, the big rocket fired in a soundless crash. For 247 seconds the rocket blazed, a time period astronaut Jim Lovell described as the "longest four minutes I’ve ever spent."

It was a splendid and epochal moment. Sixty-nine hours and 15 minutes after throwing off its shackles from the launch pad, Apollo 8 locked into lunar orbit.

No one on Earth knew that this had happened. This was a time of cliff-hanging suspense, a time to count the minutes and seconds that must pass before Apollo 8 emerged from the lunar back side and could send the desperately hoped-for signal of success. Apollo 8 communicator astronaut Jerry Carr kept up a persistent call of “Apollo 8 ... Apollo 8 ... Apollo 8 ...”

After what seemed like an eternity, headsets and speakers crackled. Smooth and calm as always came the voice of Jim Lovell:

"Go ahead, Houston."

Those three words — coming at just the instant they should have — sent Mission Control into a bedlam of cheering, whistling, shouting and applause. Electronic signals flashed their message on the big viewing board. The Apollo 8 was in an orbit 60 by 168.5 miles above the moon. Later, on the third loop around the moon, the craft’s main engine fired again and dropped Apollo 8 into the desired, nearly circular orbit of 60.7 by 59.7 miles.

A thrilled global audience was waiting for the real story from space. It had nothing to do with numbers, velocity, or the technical details of the spacecraft, or its parameters of celestial balance around the moon. The interest of those on Earth lay in one predominant direction:

What did it look like?

"Essentially gray, no color," reported Lovell, the first man ever to hold the job of lunar tour guide. He described the surface as "like plaster of Paris or a sort of grayish beach sand." In the first of two telecasts from lunar orbit, the astronauts relayed vivid pictures of a wild and wondrous landscape, pitted with massive craters.

"It looks like a vast, lonely, forbidding place, an expanse of nothing ... clouds of pumice stone," Borman said. Lovell saw the distant Earth as "a grand oasis in the big vastness of space." Anders added, "You can see the moon has been bombarded through the eons with numerous meteorites. Every square inch is pock-marked."

Anders said most of moon's backside was too rugged for a manned landing. “It looks like a sandpile my kids have been playing in for a long time," he said.

Lovell spoke eloquently. "The vast loneliness is awe-inspiring, and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth."

That Christmas Eve was like none other in the long history of celebrating the occasion. While millions of families gathered in homes throughout the planet, the three men orbiting the moon continued taking sharp motion pictures and hundreds of clear color photographs to share with Earth.

Then Bill Anders spoke, not just to Mission Control, but to the entire world listening to his words from so far away. "For all the people on earth," he said, his emotions unmasked, “the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send you.” A brief pause, and then Anders stunned his audience as he began reading from the verses of the book of Genesis:

"In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth. ...” Anders read the first four verses. Lovell read the next four. Borman read two more verses: "... God saw that it was good." Then he sent to the world a special Christmas message:

"And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you — all of you on the good earth."

Apollo 8 raced around the cratered landscape below, and Frank Borman was again stunned. Suddenly he could see his home planet "rising" above the lunar horizon. "This is the most beautiful, heart-catching sight of my life," he said.

The commander reached for his camera. The "rising" Earth that Borman photographed would become a U.S. postage stamp, a keepsake for billions.

More from 'Moon Shot':

- Yuri Gagarin: 50 years later, relive the first space odyssey

- Alan Shepard: How America's first astronaut 'got it done'

- John Glenn: A mystery surrounded the first American in orbit

- Apollo 1 fire: How a spark touched off Apollo program's darkest hour

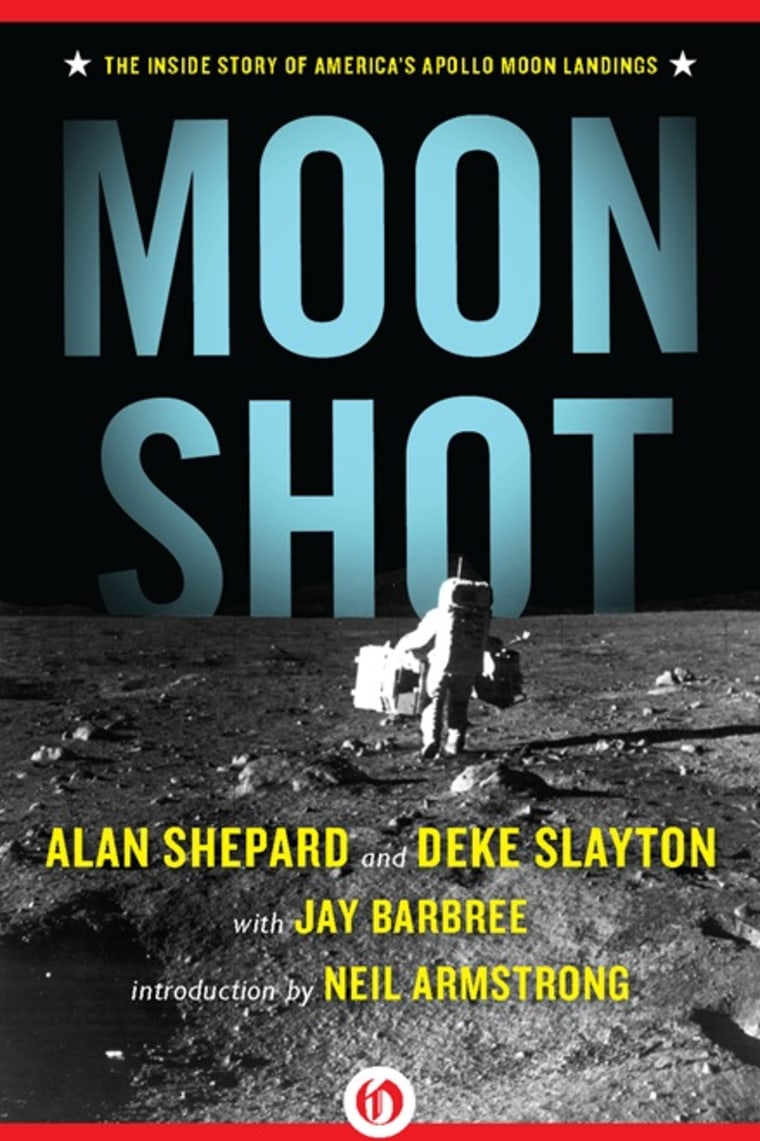

Excerpted from "Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings," by Alan Shepard and Deke Slayton with Jay Barbree. Reprinted with permission. Published by Open Road Integrated Media, copyright 2011. "Moon Shot" is available from , , , and .