A venerable NASA spacecraft could pop out of our solar system into interstellar space as early as next year, a new study suggests.

The Voyager 1 probe, which is now about 11 billion miles from Earth, has entered an unexpected "transition zone" at the edge of the solar system, according to the study. This finding, along with observations by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, hints that Voyager may be about to go where no man-made object ever has — into the space between the stars — a few years earlier than previously thought.

"Perhaps by the end of 2012, we will be out in the galaxy," said the study's lead author, Stamatios Krimigis, of Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory.

Where the solar wind turns a corner

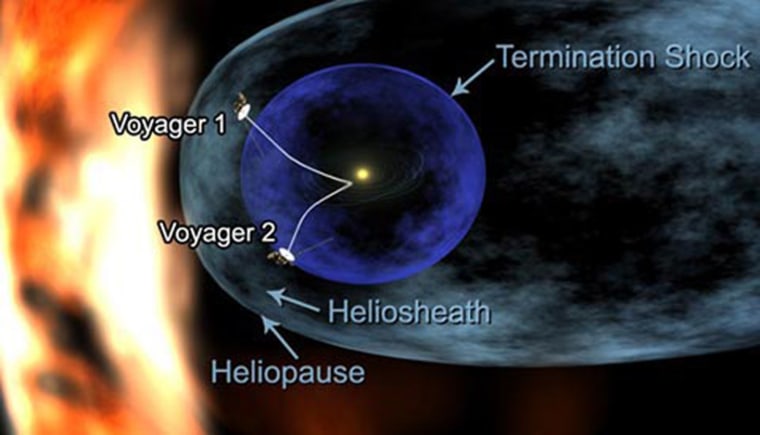

Our sun's sphere of influence, composed of solar plasma and solar magnetic fields, is called the heliosphere. This gigantic structure is about three times wider than the orbit of Pluto. On the outskirts of the heliosphere lies the heliosheath, a turbulent region at the outer reaches of the solar system.

At the edge of the heliosheath is the heliopause — the demarcation line between our cosmic neighborhood and interstellar space.

Voyager 1, which launched in 1977, is currently plying the heliosheath, as is its twin, Voyager 2. Recently, Voyager 1 stumbled into a part of the heliosheath that scientists didn't know existed.

In this region, the outward speed of the solar wind — the charged particles streaming from the sun — is essentially zero. Voyager 1's measurements show it dropping from about 130,000 mph in August 2007 down to zero by April 2010. And it hasn't picked up since.

It's not that the solar wind has ceased altogether out there; rather, it’s apparently being blown sideways by a powerful interstellar wind, researchers said. This find, first announced at a conference in December, is reported more fully in the new study and backed up with several more months' worth of data.

The nature and extent of this "transition zone" should come as a surprise to many scientists, who had predicted a relatively sharp boundary between the heliosheath and interstellar space, researchers said.

"It's at variance with all the theoretical models that anybody has come up with so far," Krimigis told Space.com. "Nobody predicted that we would go through this region of zero velocity, where essentially the solar wind would be sort of sloshing around and not doing anything."

Leaving the solar system

Krimigis and his colleagues also wanted to figure out just how far Voyager 1 has to go before it reaches interstellar space. So they enlisted the aid of another NASA spacecraft, the Saturn - studying Cassini probe.

The researchers looked at Cassini's measurements of energetic neutral atoms flowing out of the heliosheath. This information, combined with Voyager 1 observations of charged particles, gave them an idea of how wide the heliosheath is, and by extension where its edge — the heliopause — is located.

The team calculated that interstellar space likely begins about 11.3 billion miles from Earth. So Voyager 1 appears to be almost there. Since the probe covers about 330 million miles every year, it could pop out of the solar system as early as next year — a surprise, since previous estimates had pegged the probe's exit at 2015 or so.

That's not a sure thing, however; the calculation has some uncertainty attached to it. In fact, the heliopause could lie anywhere from about 10 billion to 14 billion miles from Earth, researchers said.

"It could happen any time, but it may be several more years," said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., who was not involved in the new study.

So researchers will doubtless be scrutinizing Voyager 1's data over the coming months and years, looking for any signs that the probe has officially crossed the heliopause.

"I think we'll know it when we cross it," Stone told Space.com. "The direction of the (magnetic) field will change when we get out there, and probably its strength as well."

Another likely sign, Krimigis said, would be a sudden drop in the density of hot particles, which are common in the heliosheath, and higher readings of the colder particles thought to populate interstellar space.

Krimigis and his colleagues report their results tomorrow in the June 16 issue of the journal Nature.

The Voyagers' instruments are powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert the heat emitted by plutonium's radioactive decay into electricity. The instruments should have enough juice left to keep taking measurements until at least 2020, researchers have said.

Voyagers still truckin'

The main mission of both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which is currently about 9 billion miles from Earth, was to study Jupiter, Saturn and their moons.

During the 12 years of their initial planetary mission, the twin probes returned a great deal of data that changed scientists' understanding of our cosmic backyard, according to Stone.

"Time after time, our view of the solar system greatly expanded, as we saw the diversity of bodies in the solar system," he said.

But when that phase of the mission was over, the Voyagers just kept cruising and contributing. And now, nearly 34 years after their launch, the spacecraft are still delivering key information — this time from the solar system's edge. Just last week, for example, researchers analyzing Voyager data announced the surprising discovery of huge magnetic bubbles out in the heliosheath.

"Our motto (at first) was 'Saturn or bust,'" said Krimigis, who has worked on the Voyager mission for four decades. "That was the original objective, to go to Saturn. Everything else was gravy. And now, here we are."

You can follow Space.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: . Follow Space.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter and on .