Scientists on Thursday shared fresh pictures and data about Mercury, showing mysterious pits on the planet in unprecedented detail and shedding new light on its unusual magnetic field.

The revelations come from NASA's $446 million Messenger mission, which began orbital operations in March and is now a quarter of the way through its yearlong planet-mapping mission. Messenger stands for "MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging."

Earlier probes have looked at Mercury, the closest planet to the sun. But Messenger is providing the highest-resolution imagery ever taken, including pictures of areas that have never before been seen close up.

"We had many ideas about Mercury that were incomplete, ill-formed. ... Many of those theories are now being cast into the dustbin of science," the Carnegie Institution of Washington's Sean Solomon, principal investigator for the Messenger mission, told journalists at a NASA news briefing.

A casual observer might look at the cratered planet and assume it's a dead world like the moon, but that's not so, said Messenger project scientist Ralph McNutt, who is based at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory.

"Comments to the contrary, Mercury ain't the moon," he said. And it ain't like any of the other terrestrial planets in the inner solar system, either.

What the new pictures reveal

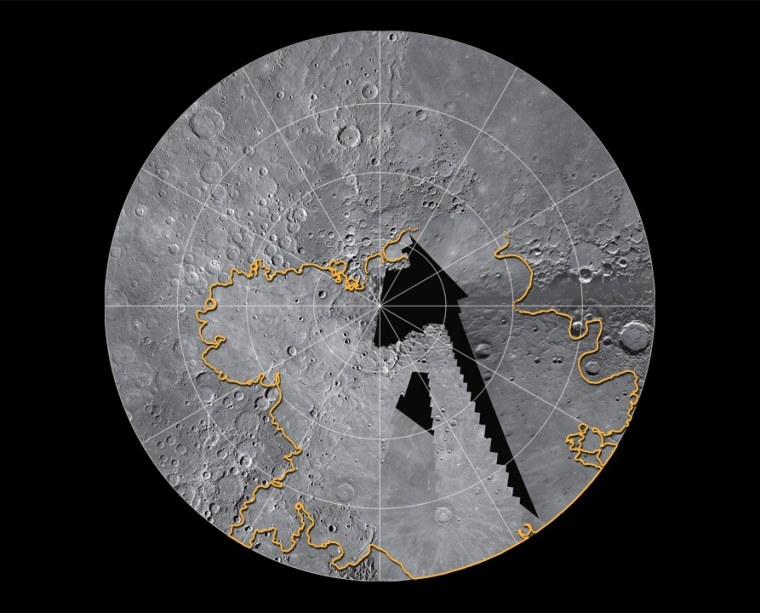

The orbital images reveal broad expanses of smooth plains near Mercury’s north pole. Flyby images from Messenger and from Mariner 10 in the 1970s indicated that smooth plains may be important near the north pole, but much of the territory was viewed at unfavorable imaging conditions. The latest images show that the plains are likely among the largest expanses of volcanic deposits on Mercury, with thicknesses of up to several kilometers.

The broad expanses of plains confirm that volcanism shaped much of Mercury’s crust and continued through much of Mercury’s history.

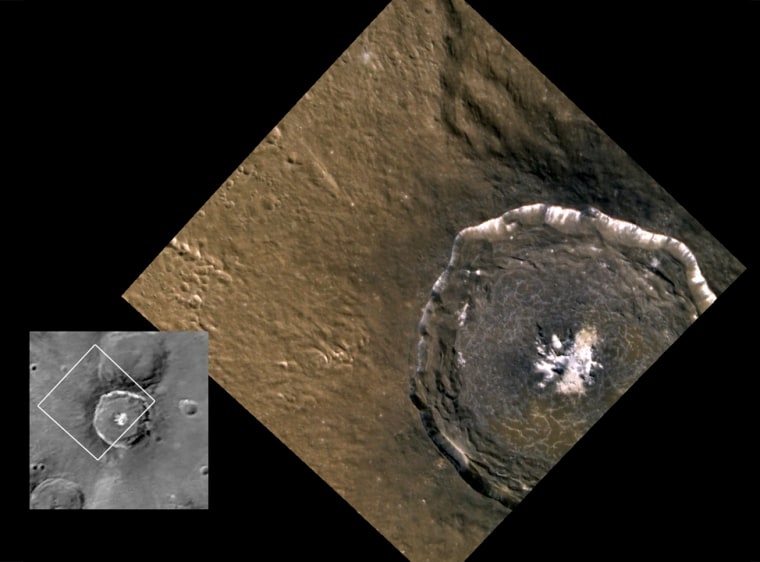

Images taken during Messenger's flybys had detected bright, patchy deposits on some crater floors. Without high-resolution images to obtain a closer look, these features remained only a curiosity. The latest images now show that these patchy deposits are clusters of rimless, irregular pits varying in size from several hundred feet to a few miles wide. These pits are often surrounded by diffuse halos of more reflective material, and are found on central peaks, peak rings, and rims of craters.

"The etched appearance of these landforms is unlike anything we've seen before on Mercury or the moon," Brett Denevi, a staff scientist at the Applied Physics Laboratory and a member of the Messenger imaging team, said in a news release. "We are still debating their origin, but they appear to be relatively young and may suggest a more abundant than expected volatile component in Mercury's crust."

Looking beyond the pictures

An analysis of the elemental composition of Mercury's surface has shown that it differs markedly from that of the moon, and from that of Earth, Venus and Mars as well.

Observations have revealed substantial amounts of sulfur at Mercury's surface, lending support to previous suggestions that sulfide minerals are present. This discovery suggests that the original building blocks from which Mercury formed may have been less oxidized than those that formed the other terrestrial planets. The result also hints that sulfur-containing gases may have contributed to past explosive volcanic activity on Mercury.

Topography data of Mercury's northern hemisphere reveal the planet's large-scale shape in high detail. The north polar region is a broad area of low elevations, whereas the overall range in topographic heights seen to date exceeds 5 miles (9 kilometers).

Two decades ago, Earth-based radar images showed deposits that were thought to consist of water ice and perhaps other ices near Mercury's north and south poles. These deposits are preserved on the cold, permanently shadowed floors of high-latitude impact craters. Messenger is testing this idea by measuring the floor depths of craters near Mercury's north pole. The craters hosting polar deposits appear to be deep enough to be consistent with the idea that those deposits are in permanently shadowed areas.

Future studies are expected to confirm whether the deposits indeed contain water ice, as expected.

Magnetic mysteries

During the first of three Mercury flybys in 1974, Mariner 10 discovered bursts of energetic particles in the planet's Earthlike magnetosphere. Four bursts of particles were observed on that flyby.

Scientists were puzzled that no such strong events were detected by Messenger during any of its three flybys of the planet in 2008 and 2009. But now that the spacecraft is in near-polar orbit around Mercury, energetic events are being seen regularly.

The Messenger team also found that Mercury's magnetic "equator" is 300 miles (480 kilometers) north of the planet's physical equator, suggesting that the magnetosphere is asymmetrical. Saturn has a similar but far less pronounced asymmetry, the scientists said.

McNutt told journalists that more revelations would be coming as Messenger's mission proceeds. "Keep following us — the best is yet to be," he said.

The Messenger spacecraft was designed and built by the Applied Physics Laboratory, which manages and operates the mission for NASA.

This report includes information from NASA, Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory and the Carnegie Institution of Washington.