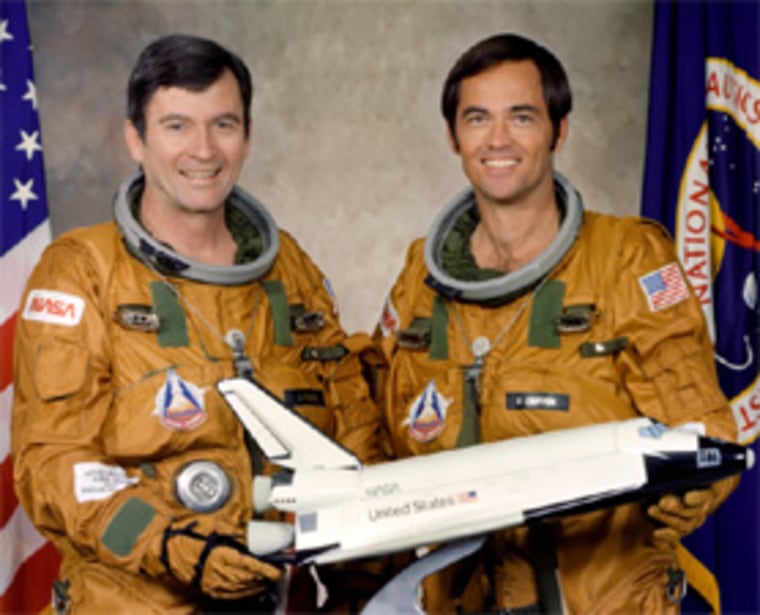

When astronauts John Young and Bob Crippen strapped themselves inside space shuttle Columbia for the shuttle program's debut mission in 1981, known as STS-1, it was the first time people had been aboard for a spaceship's trial run.

"(NASA) did discuss whether we should go modify it so we could fly unmanned. That was a serious discussion," Crippen said. "But both John Young and I lobbied hard that they ought to put us onboard because we thought the chance for success was much better having people on there."

What NASA didn't know at the time was that there was a 1-in-9 chance the astronauts would not make it back alive. At the time, managers put the odds of losing the shuttle and its crew at 1-in-100,000.

Safety upgrades, including those initiated after two fatal accidents, have made the shuttle 10 times safer than it was in its early years, but the odds of a catastrophic accident are still high — about 1 in 90.

That is the largely unspoken part about why NASA is retiring its shuttle fleet after a final cargo run to the space station next month.

The primary driver is money — preparing the shuttles for flight is extremely labor-intensive, which drives its $4 billion-a-year operating expense. The other reason is to free up funds for NASA to develop new spaceships that can travel beyond the space station's orbit, where the shuttles cannot go.

The shuttles' end was the last thing on the minds of Crippen and Young as they sat on the launch pad 30 years ago on April 12, 1981, awaiting blastoff.

"I was more worried about the software," Crippen said. "The vehicle was so complicated; I thought there was a high probably of a scrub. It was actually only when we got inside of a minute in the countdown that I looked at John and said, 'Hey, I think we might do it.'"

Crippen, who led a panel discussion about the shuttle history at an industry conference in Orlando earlier this year, said his heart rate shot up to about 130, while his commander, an Apollo moon veteran, stayed calm.

"He says, 'Crip, when they're getting ready to light off 7 million pounds of thrust under you, if you aren't a little bit excited, you don't understand what's going on.'"

When the shuttle's booster rockets fired up, lifting the ship off the ground, Crippen said he wasn't concerned about surviving the trip. "Probably my main thought after liftoff was 'Don't let me screw up,'" he said.

STS-1 was successful, orbiting the Earth 37 times, lasting 54.5 hours.

Crippen went on to fly three more shuttle missions, become the shuttle program director and then head of NASA's Kennedy Space Center before moving on to executive management positions in the aerospace industry. He retired in 2001 as president of shuttle booster manufacturer Thiokol Propulsion.

Young, who also flew aboard the first manned Gemini spacecraft, which preceded the Apollo program, made one more shuttle flight, spent 13 years as the agency's chief astronaut and another 17 years as a key safety oversight manager until his retirement in December 2004.

An earlier version of this report misstated the odds of a catastrophic accident for STS-1.