Possibly as many as a million people are expected to descend on Kennedy Space Center this week in hopes of witnessing the final launch of the space shuttle.

Astronauts have lifted off from Florida 165 times, and the only one of those launches that drew as much attention as Atlantis' final shuttle flight was the 21st liftoff: Apollo 11.

Today, the mood and atmosphere of this place is very different. There’s a lot of uncertainty. The only sure bet is that following the space shuttle’s farewell flight, most of the members of the launch team will be out of job.

Critics say NASA is in shambles. There is no defined mission for astronauts' future. But NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden, a veteran astronaut himself, says hold on.

"I’m not about to let human spaceflight go away on my watch," he declared last week.

Boeing and SpaceX could have Americans flying their commercial spacecraft by 2015, and Bolden says astronauts could be heading for deep space in 2016.

Forty-two years ago this month, the scene was in sharper focus. The mission to land astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon came at the height of prestige for America’s space program. The country was first. Americans were beating the Russians. A decade-long race to put a human on another world was about to end. Armstrong and Aldrin were riding their lunar lander, known as Eagle, to the finish line.

First on the Moon:

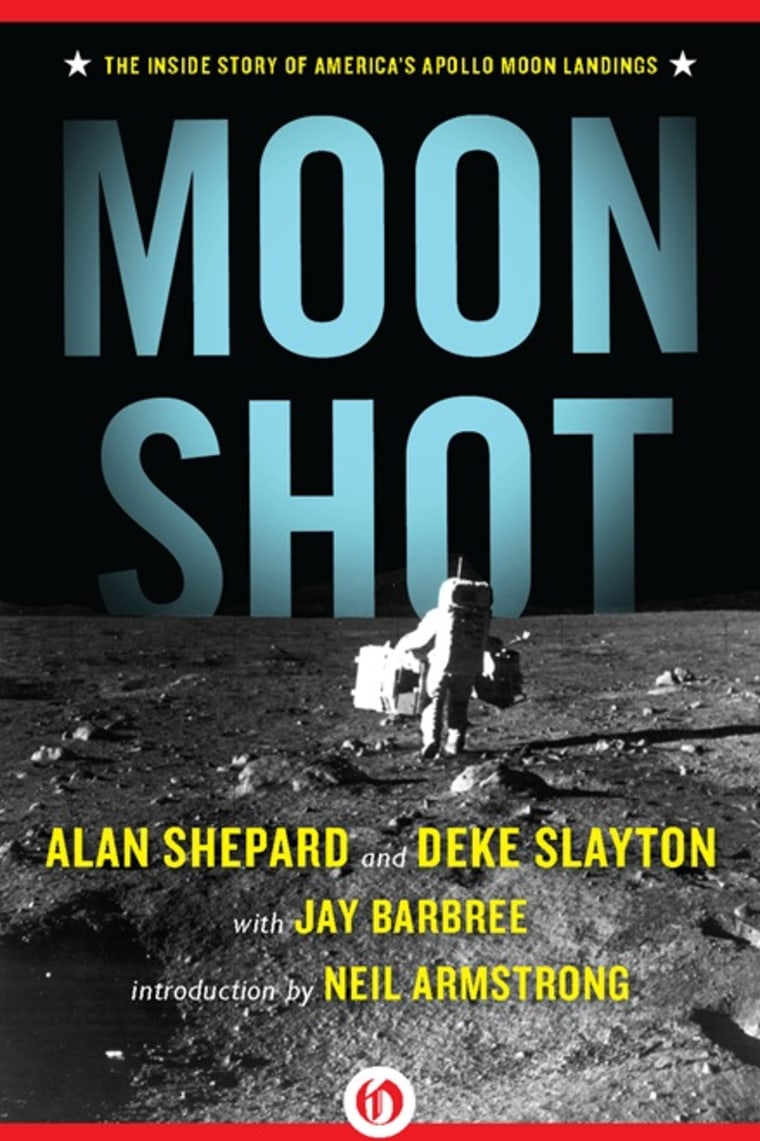

An excerpt from "Moon Shot":

Thirteen hundred feet above the moon’s surface, Eagle began its final descent. Flames gushed downward as the craft slowed. Neil Armstrong had flown his mission right along the edge of the razor. He and Buzz Aldrin functioned as one mind. Now they were doing more than falling moonward. They were so close Neil had to fly this ship. He punched "PROCEED" into his keyboard. The computer would handle the immediate descent tasks. Buzz would back up both man and electronic brain so Neil could adapt to flying in vacuum.

Both men looked through the triangular windows to study the surface of the moon. They’d made simulated runs so many times they knew their intended landing site as well as they knew familiar airfields back home. Almost immediately, they noticed that they weren’t where they were supposed to be.

Damn!

Eagle had overshot the landing zone, Home Plate, by four miles. A slight navigational error and a faster-than-intended descent speed accounted for the Eagle missing its planned touchdown on a selected smooth spot on the moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

Neil studied the surface rising toward them. Boulders surrounded a yawning crater wider than a football field, and Eagle was running out of fuel and headed straight for it. No time to waste.

In the lunar void there was no gliding to conserve fuel. Eagle was only dead weight in vacuum. There also was no opportunity to orbit again for another try at landing. Their only chance to succeed was to land.

Neil Armstrong gripped the hand controller in his fist, firm and strong, with a touch honed by years of flight in jets and rockets. He knew the “thin edge” well, both in atmosphere and in hurtling through orbit. Now he had to fly as he’d never flown before. Knowledge, experience, the touch — the skill, the Gemini 8 emergency, the X-15 rockets skimming over Edward Air Force Base's hard sands, ejecting from his crippled jet fighter over Korea when he was 21, dammit, even ejecting from the lunar lander trainer before it crashed. All of it, everything came to this one moment.

The Ohio farm boy, Neil Armstrong came from the same soil as Orville and Wilbur. This was his Kitty Hawk, and he needed to hand-fly man’s first landing on the moon the rest of the way.

His fingers alternately tightened and eased his grip on the controls.

Eagle was sailing down at 20 feet per second. Neil nudged the power, slowing to nine feet per second.

He attuned his senses to the rocking motions, the nudges, and the skidding motions of the 16 small positioning thrusters that kept Eagle aligned throughout its descent. A level touchdown was their ticket to safety, survival, and return home.

Mission Control listened, mesmerized and awed, to the voices closing in on the lunar surface. Neil flew Eagle. Buzz watched the landing radar, called out numbers that represented split-second judgment and maneuvering.

"Five hundred forty feet [height above the surface], down at 30 [feet per second] ... down at 15 ... 400 feet, down at nine ... forward ... 350 feet, down at four ... 300 feet, down three and a half ... 47 forward ... one and a half down ... 13 forward ... 11 forward, coming down nicely ... 200 feet, four and a half down..."

Despite the confidence of the astronauts’ voices, there was a looking problem: There was no place to land. Rocks, huge boulders and deadly craters were strewn everywhere.

Mission Control was dead silent.

Neil fired the Eagle’s maneuvering jets. Eagle scooted across rubble billions of years old. Finally, beyond a field of boulders, a smooth, flat area.

Astronaut Charlie Duke, Mission Control’s communicator with Eagle, sounded the warning. "Sixty seconds."

There was one minute of fuel left. In 60 short seconds the rocket power flaming beneath Eagle would burn out.

Neil Armstrong calmly aimed for his new landing site. The Eagle’s commander kept one thought uppermost in his mind.

Fly.

Eagle swayed gently from side to side as the thrusters responded to Neil’s experienced hand.

Far away, down through the atmosphere and the clouds, enclosed within Mission Control, the flight controllers were almost frantic with their inability to do anything more to aid Neil and Buzz.

Flight director Gene Kranz spoke to Charlie Duke. "You’d better remind them there ain’t no damn gas stations on the moon."

Charlie nodded and keyed his mike. A timer stared at him. "Thirty seconds."

"Light’s on."

This time the announcement was from Buzz Aldrin as he watched an amber light blink balefully at him from the master caution-and-warning panel. It was the low-fuel signal.

Buzz then intoned the numbers like a priest, steady and clear, voicing the final moments flashing away.

"Seventy-five feet," he called out.

"Six forward..."

"Light's on ... down two and a half ... 40 feet, down two and a half . . .”

Eagle was now slipping downward 50 feet above the moon. Men and machine embraced a new level of potential danger. This close to the surface, they had no margin for error. If their space vessel failed them, or if they ran out of fuel, they would not have time to abort. If they ran into any problem this close, there would be no time for circuits and solenoids and explosive charges to separate the Eagle from its lifeless descent stage, no time for fuel to stream through lines into the ascent stage’s combustion chamber beneath their boots, no time for the fuel to ignite and hurl them upward before they crashed.

Time was their enemy.

"Thirty feet ... two and a half down...”

Then, the magic words!

"Kicking up some dust ...

"Faint shadow..."

So close now! So close!

There was no turning back. The door behind them had closed.

"Four forward ... drifting to the right a little..."

Everyone in Mission Control, and in the visitors’ viewing gallery, and throughout the vast halls of NASA, everyone anywhere who knew what was happening just above the moon was hoping, praying, straining.

Fuel flashed away. Neil Armstrong flew Eagle with the smooth touch of a naval aviator landing his jet on a storm tossed carrier.

On Earth, billions of hearts pounded madly.

Then, Buzz Aldrin spoke the first words from the surface of the moon. "Contact light! OK, engine stop. Descent engine command override off..."

In Houston, CapCom Charlie Duke was choking with relief. But he still needed voice confirmation. He wanted to hear the words.

"We copy you down, Eagle," he radioed. Then he waited.

Three seconds for the voices to rush back and forth, Earth to the moon and moon back to Earth.

Those three incredible seconds, and then came the call.

Neil’s voice was calm, confident, most of all clear.

"Houston, Tranquility Base Here. The Eagle has landed.”

More from 'Moon Shot':

- Yuri Gagarin: 50 years later, relive the first space odyssey

- Alan Shepard: How America's first astronaut 'got it done'

- John Glenn: A mystery surrounded the first American in orbit

- Apollo 1 fire: How a spark touched off Apollo program's darkest hour

- Apollo 8: How a round-the-moon mission changed our perspective

Excerpted from "Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings," by Alan Shepard and Deke Slayton with Jay Barbree. Reprinted with permission. Published by Open Road Integrated Media, copyright 2011. "Moon Shot" is available from , , , and .