A year after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, American diplomats are still trying to repair the damage with critics of the war.

At the United Nations, Secretary General Kofi Annan has said that American credibility has been hurt, and needs to be restored.

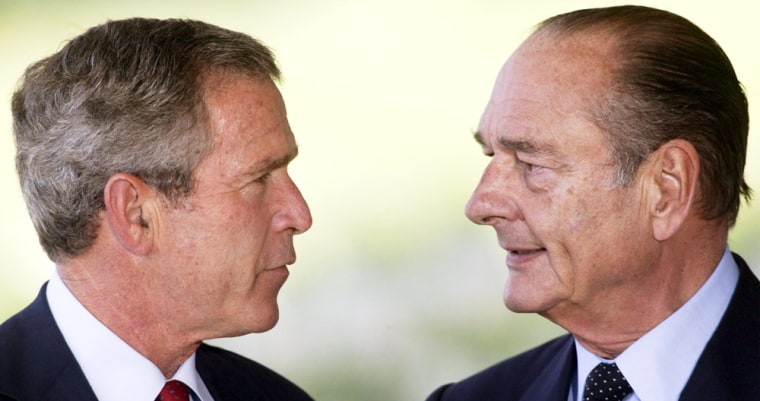

The leaders of France and Germany, while trying to make amends on a personal level with President Bush, are still saying, "I told you so," because of the U.S. failure to find weapons of mass destruction.

And even though several intelligence services contributed to the CIA's pre-war judgments about Saddam Hussein's weapons, the reputation of the American intelligence agency has been hurt, at home and abroad.

Mending fences

How does this affect foreign policy? Already there are signs that the administration is now more willing to work with allies to solve multilateral problems, like weapons' proliferation.

This is partly to avoid reinforcing the criticism that the United States was too willing to go it alone in Iraq. But in fact, it is also a response to domestic politics.

In an election year, no administration wants to take on intractable issues by itself. So, for the first time, there seems to be more flexibility on a range of subjects, from Libya to North Korea.

On Libya, the administration has negotiated a major breakthrough, disarming Tripoli in return for a promise to normalize relations.

On North Korea, American negotiators have hinted that Pyongyang could win economic support in exchange for giving up its nuclear programs, something the Bush White House has long refused to even discuss.

And, although the relationship is still fractious, the United States and France found it mutually beneficial to work together to try to resolve the crisis in Haiti.

Post-war image problems

At the same time, the unexpectedly difficult post-war occupation and the failure to find catastrophic weapons in Iraq have combined to complicate American diplomacy in the Middle East.

Instead of the momentum the administration hoped to gain throughout the Arab world from its show of military might against Iraq, the security challenges since the war have created to many an image of a powerless giant, pinned down by Iraqi insurgents and foreign fighters.

Critics of the administration say it has not shown the same dedication to Middle East diplomacy that it has to military intervention. The continuing stalemate between Israel and the Palestinians is, in the region, blamed more on American diffidence than the intractability of Yasser Arafat or Ariel Sharon.

In the aftermath of a war fought to eliminate the threat of weapons of mass destruction, the world discovered that other countries not targeted for American attack had even more advanced nuclear programs than Iraq.

After years of ignoring obvious signs that Pakistan was helping rogue nations obtain nuclear technology, U.S. intelligence confronted Pakistanis with overwhelming evidence that the father of their nuclear program, A.Q. Khan, has been selling nuclear secrets to Libya, Iran, and North Korea.

Pakistan's President Pervez Musharraf was finally forced to indict Khan, and then quickly pardoned him. But, most experts find it difficult to believe that Pakistan's military, its intelligence service, and perhaps Musharraf himself, were not aware all along of Khan's extensive operation.

Homeland Security

There is also a continuing debate over whether the war has made America safer or more vulnerable. The heads of the CIA, Defense Intelligence Agency, and FBI all testified to the Senate Intelligence Committee at the end of February that the country is safer than it was a year ago.

But at the same time, they said that arresting al-Qaida leaders has not eliminated the threat. Splinter groups have adopted al-Qaida's mission of attacking the United States' homeland with weapons of mass destruction.

CIA director George Tenet warned that the possibility of a poison attack or the use of anthrax by a terror group is very real.

Would this be true had the United States not attacked Saddam Hussein? U.S. officials say absolutely.

But the continuing al-Qaida threat gives ammunition to foreign leaders and political opponents who say the threat from al-Qaida was greater than that of Iraq, and should have been a higher priority.

The defeat of Spain's conservative government last weekend in the aftermath of the Madrid train bombings underscored the perils for allies who supported the U.S. campaign.

Reluctance to intervene elsewhere

Foreign policy has also been affected by post-war reluctance to use force again unless absolutely necessary, because the U.S. military is now spread too thin. This was seen principally in Haiti, where critics said the United States was dragging its feet in contributing military aid to help diffuse the crisis.

Perhaps the biggest effect of the war is the perception that the State Department and Secretary Powell, having lost the internal battle over Iraq to hawks at the Pentagon, are no longer in charge of American foreign policy.

The impression of diplomatic weakness, whether accurate or not, can undercut U.S. effectiveness on a range of issues, from the Middle East to North Korea.

So, a year after the United States invaded Iraq, America is now turning to the United Nations for help in Iraq, and France for help in Haiti. Ironies abound, none of them particularly helpful for the reputation of American foreign policy at home or abroad.