Long after the United States and the Soviet Union put their Cold War space race to bed, another cosmic competition is heating up.

This one is taking place in the private sector. A handful of companies are vying for the right to carry American astronauts into orbit — a capability the nation temporarily lacks, now that NASA's space shuttle fleet has seen its last launch.

The iconic shuttle program will end in a matter of hours, when Atlantis touches down at Florida's Kennedy Space Center early Thursday. Russian Soyuz vehicles will fly NASA astronauts to the International Space Station over the short term, but the space agency wants commercial craft to take over this role as soon as safely possible.

Several firms are in the running to provide this taxi service beginning as early as 2015.

"In the fall of '15, we'll do a test flight with two Boeing test pilots. That one will go to [the space] station," said John Elbon, Boeing's program manager for commercial crew transportation. "And then we'll be ready at the end of '15 to do operational flights."

Big names in the race

Boeing scored $92.3 million from NASA in April during round two of the space agency's Commercial Crew Development Program (CCDev-2), which seeks to spur private spaceflight capabilities. The company, one of four to be granted funds by NASA during CCDev-2, will use the money to keep developing its new crew-carrying space capsule, which it calls the CST-100.

Boeing plans to hold a parachute drop test next spring and to start conducting uncrewed test flights in 2014 in the lead-up to manned missions with the CST-100 in 2015, according to Elbon.

"I think we're on a low-risk path to get to those milestones," Elbon told Space.com in Florida earlier this month, just before Atlantis' final liftoff. "We'll see how many others are successful at doing that as well."

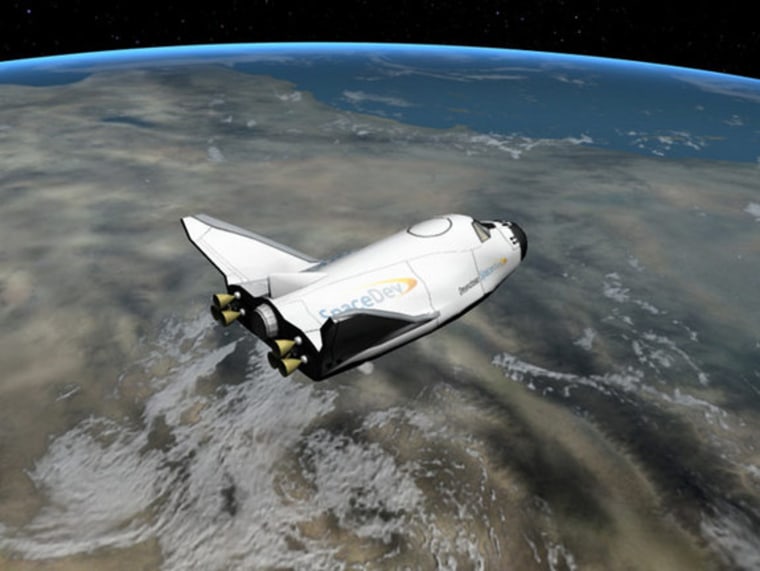

Another of the CCDev-2 grant winners, Sierra Nevada Corp. of Louisville, Colo., got $80 million to help its Dream Chaser along. This winged vehicle, which looks like a miniature space shuttle, is designed to carry seven astronauts to low-Earth orbit and back. Like the CST-100, the Dream Chaser is coming along nicely, according to officials of its company.

"We are in the midst of our first build of the first vehicle right now. It's under construction," Sierra Nevada Chairman Mark Sirangelo told reporters in Florida earlier this month. "We'll be conducting our first orbital tests in 2014, with service in 2015."

Blue Origin and SpaceX, too

NASA gave Blue Origin, based in Kent, Wash., $22 million under CCDev-2. The company, which was established by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, may use the money to further the development of its New Shepard vehicle. However, Blue Origin is generally very tight-lipped about its plans, so it's tough to say for sure what the firm is up to.

The California-based Space Exploration Technologies, better known as SpaceX, got $75 million during CCDev-2. Unlike the other grantees, SpaceX has actually launched its vehicle into space. Last December the firm blasted its Dragon capsule to orbit aboard its Falcon 9 rocket, then fished the Dragon out of the Pacific Ocean after it splashed down.

SpaceX thus became the first private company ever to launch a spacecraft to Earth orbit and bring it back to terra firma.

SpaceX has a $1.6 billion NASA contract to use the Dragon/Falcon system to carry cargo to the International Space Station. But the company designed Dragon all along to carry crew, and it's in the process of performing the necessary upgrades, officials have said.

Dragon must make at least 11 more unmanned flights, and the Falcon 9 must blast off at least 17 more times, before the system is ready to carry passengers, SpaceX officials have said. But the company is confident it will finish at the front of the pack.

"Given the extensive manifest of Falcon 9 and Dragon, the SpaceX system will mature before most other systems will be developed," SpaceX chief executive and chief rocket designer Elon Musk wrote on his blog in January.

Others in the game

The new private space race isn't restricted to CCDev-2 grantees; other companies are in the game.

One of these is the Virginia-based Orbital Sciences Corp., which is developing its own space plane, called Prometheus. This vehicle could be ready for test flights as early as 2014, company officials have said.

And Excalibur Almaz, based on the Isle of Man, aims to repurpose space-flown Soviet-era hardware designs. This approach, Excalibur Almaz says, will cut development time and costs considerably.

Rocket developers have become involved in the race as well. While SpaceX is developing its own launch vehicle, the other private spaceship makers will rely on third parties to blast them to orbit.

United Launch Alliance — a joint effort of Boeing and Lockheed Martin — is working to upgrade its rockets for manned spaceflight, while Alliant Techsystems (ATK) has teamed with the French company Astrium to build a human-rated launch vehicle called Liberty.

ATK and Astrium have said Liberty could take to the skies in 2013, with operational capability in 2015.

So, while many observers lament the end of the shuttle era and the onset of a multi-year gap in American manned spaceflight, many at NASA and in the private sector say the future is bright.

With the burden of ferrying astronauts to low-Earth orbit shifted to commercial craft, NASA says it will be free to focus on exploring farther afield. The space agency plans to send astronauts to an asteroid by 2025 and to Mars by the mid-2030s.

"I know the transition from our flagship program to a new chapter in human spaceflight has not been easy. Change never is," NASA chief Charlie Bolden said in a video just after the shuttle Atlantis blasted off July 8. "I want to make clear that American leadership in space will continue for at least the next half-century, because we've laid the foundation for success."

You can follow Space.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter:. Follow Space.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter and on .