On the eve of the U.S. invasion to topple Saddam Hussein, officials here say Iran's Islamic leaders could hardly believe their luck. Washington, heretofore the "Great Satan," was about to do Iran a great service -- by taking out the man whose troops, often using chemical weapons, killed more than a half million Iranians during the 1979-1989 Iran-Iraq war.

But while the mullahs, whose popular support has waned since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, sat back and watched Saddam fall, the chattering classes had other ideas.

"After Bush is done with Saddam, have him send American troops over here," went the common refrain in Tehran.

And in the aftermath of President Bush's "axis of evil" speech in January 2002, there was plenty of speculation that Washington just might.

Reality check

But a year after U.S. troops got mired down in Iraq, the mullahs have gone nowhere. On the contrary, they are fresh from a (questionable) election victory.

Next door in Iraq, meanwhile, the American military is stretched too thin to contemplate taking on Tehran. And international support for another "regime change" by Washington is nonexistent.

But that hasn't exactly emboldened the hard-line clerics either. The Bush administration's "war on terror" has hemmed in Iran, forcing the mullahs to take a pragmatic approach to their policy toward the United States.

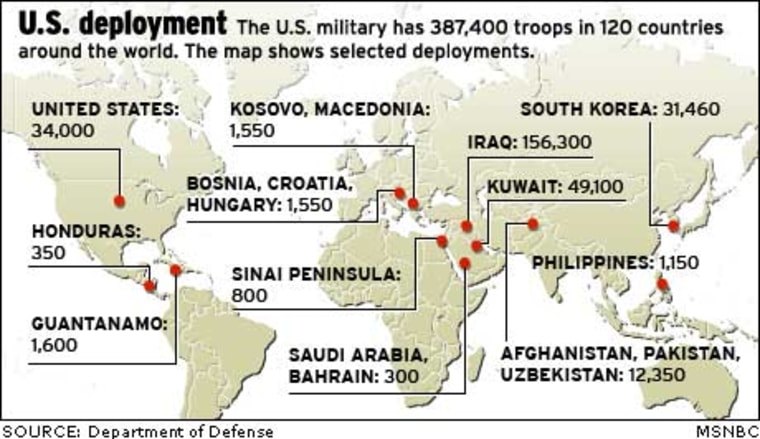

To the west, in Afghanistan, Washington has stationed nearly 13,000 troops to support its hunt for Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida remnants, and to prop up the government of pro-American Afghan President Hamed Karzai.

In Iraq, to the east, an occupation force of more than 155,000 U.S. troops is supported by U.S. warships within sight of Iran's southern Persian Gulf shores.

And to the north, Washington has curried favor with the despot leaders of the so-called "stans" -- Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan -- enabling U.S. troops to use old Soviet bases for forward operations in the region.

"Suddenly, we are neighbors," said Reza Yousefian, a prominent reformer who was banned from taking part in last month's parliamentary elections.

Neighborly ties

But will Tehran and Washington make good neighbors?

Post-9/11 U.S. foreign policy has many strange bedfellows. (Were it not for regional oil reserves and the hunt for al-Qaida, the "stans" have little to offer America.)

In Iran's case, U.S. officials say al-Qaida operatives fled from Afghanistan and Pakistan into Iran after Washington toppled the Taliban in 2002. Some officials believe Iran may be holding Osama bin Laden's son, Saad, and other al-Qaida luminaries, as bargaining chips in future negotiations with the United States.

So can common interests bring two old enemies together?

Reformers like Yousefian think so. But parliamentary elections on Feb. 20 threw reformers like him onto the streets, after the hard-line mullahs banned more than 2,000 reformist candidates from taking part in the vote.

But there are plenty of hurdles to a U.S.-Iran rapprochement, like Iran's support for Hezbollah, the anti-Israeli guerrillas in southern Lebanon, that earns Tehran a top spot on Washington's list of terrorist-sponsoring nations.

Iran's alleged pursuit of nuclear weapons also causes friction, though Tehran claims its nuclear program is solely for civilian purposes. And in Iraq, Washington suspects Tehran is exploiting its religious ties to Iraq's restless majority Shia population, and possibly turning a blind eye to anti-U.S. militants crossing into Iraq.

Still, even hard-line conservatives like Badam Chian, a top official at the Islamic Coalition Party, are taking an open view.

"It's in the interest of both countries," he said in an interview. "For 25 years, the United States has been scheming against Iran. Why doesn't Washington understand that its policy is so wrong?"

Right or wrong, American policy toward Iran has recently been the focus of diplomatic flirtation: After the Dec. 26 Bam earthquake, which killed over 40,000, Iran received its first direct American aid in 25 years; congressional leaders recently proposed a friendly visit to Iran; and Iran's ambassador to the United Nations, Mohammad Javad Zarif, has become a regular in Washington political circles.

Officials here say the parliamentary elections last month, though heavily stacked in the favor of the mullahs, were designed to hijack the agenda of popular reformers like Yousefian, who had called for diplomatic relations with the United States.

"[The hard-liners] stole our slogans," the 36-year-old reformer complained. "But maybe we should take it as a compliment, or a sign of things to come."