Standing almost directly overhead around midnight on July nights is the brilliant bluish-white star Vega, in the constellation of Lyra, the Harp.

It's the fifth-brightest star in the entire sky and the third brightest visible from midnorthern latitudes, behind Sirius and Arcturus. Also, as seen from midnorthern latitudes such as New York or Madrid, Vega goes below the horizon for only about seven hours a day, meaning that you can see it on any night of the year.

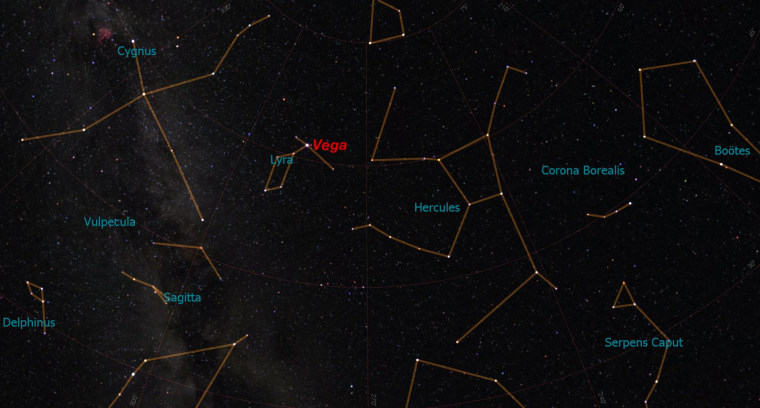

The sky map of Vega here shows how the star appears in relation to constellations and other stars.

Farther south, Vega is below the horizon for an even longer interval of time. Conversely, for Alaska, central and northern Canada, as well as central and northern Europe, Vega never sets and is readily visible on any night of the year.

Popular misconception

As a young boy I used to spend my summers at Long Island's Atlantic Beach. On clear nights, my Uncle Bob would point to Vega and tell me that it was "the North Star, the brightest star in the sky." Of course, he was wrong: the North Star is Polaris at the end of the tail of Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. Even today the idea that the North Star is the brightest star in the sky continues to be a popular misconception.

Vega is the brightest of the three stars forming the large " Summer Triangle " consisting of Vega, Altair and Deneb. It is located 25 light-years away, has a diameter about three times that of our sun and is 58 times more luminous.

In January 2002, astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., announced that features observed in a cloud of dust swirling around Vega may in fact, be the signatures of an unseen planet in an eccentric orbit around the star.

Getting the name wrong

Observations of Vega in 1983 with the Infrared Astronomy Satellite provided the first evidence for large dust particles around another star, probably debris related to the formation of planets. This discovery likely inspired Carl Sagan to place a planet orbiting Vega in his novel "Contact."

"Contact" was also made into a 1997 American film, directed by Robert Zemeckis. I personally enjoyed it for the most part, except for one thing; the mispronunciation of Vega.

Vega is correctly pronounced "Vee-ga." But between 1971 and 1977, the Chevrolet division of General Motors produced a lightweight four-cylinder automobile that was christened after Vega. The car's name was marketed as being pronounced "Vay-ga." For years thereafter, whenever I gave planetarium shows or lectured under the real sky, I would remind my audience that Vee-ga was a star, but Vay-ga was a car.

Unfortunately, it appears that the latter pronunciation carried over two decades later into the production of the film "Contact." Today I tell people that if the film's protagonist, Dr. Eleanor "Ellie" Arroway, was a real person, then as an astronomer she would have referred to the strong extraterrestrial signal as emanating from the star Vee-ga and not from the car Vay-ga. But then, that's Hollywood.

Vega also holds a rather unique place in the annals of astronomy as being the first star ever to be photographed. The historic photograph was made using the daguerreotype process at Harvard Observatory on the night of July 16-17, 1850. A 15-inch refractor was used, but nonetheless it still took an exposure of 100 seconds for Vega's image to register.

The lyre

Officially, Lyra is a lyre — a stringed instrument of the harp family used to accompany a singer or reader of poetry, especially in ancient Greece. In Greek mythology, Lyra was associated with the myth of Orpheus, the musician who was killed by the Bacchantes. After his death, his lyre was thrown into the river. Zeus sent an eagle to retrieve the lyre, and ordered both of them to be placed in the sky. This is why Lyra is often represented on star maps as a vulture or an eagle carrying a lyre, either enclosed in its wings, or in its beak.

Six stars form a combined geometric pattern of a parallelogram and an equal-sided triangle attached at its northern corner. Vega gleams at the western point of the triangle. In his classic book, "The Stars — A New Way to See Them," author H.A. Rey commented that Lyra better resembled a two-stringed zither than a traditional lyre.

But there are other interesting sights to explore here. Epsilon Lyrae, at the northern point of the little triangle where Vega is located, is known as the "double-double" star. Good eyesight reveals Epsilon is really a close pair of stars.

Binoculars readily separate the two, while a moderately large telescope shows each one divided again into two stars.

The star Sheliak is one of the two that forms the southern side of the parallelogram and appears to diminish by half of its normal brightness about every 13 days when it's eclipsed by a darker companion star. Between this winking star and its neighbor, Sulafat is the famous Ring Nebula, faintly glowing like a ghostly doughnut or a cosmic smoke ring. Visible only in large telescopes, it appears as an oval ring around a star. Millions of years ago, this star exploded, hurling out great masses of gas. We see the star now through the thin part of this gaseous envelope.

One final point. Thanks to precession, the wobbling motion of the earth's axis, in 12,000 years, our north polar axis will be pointing in the general direction of Vega and it will indeed officially become the North Star. My Uncle Bob passed away in 2009, but I'm sure that piece of news would have made him very happy.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.