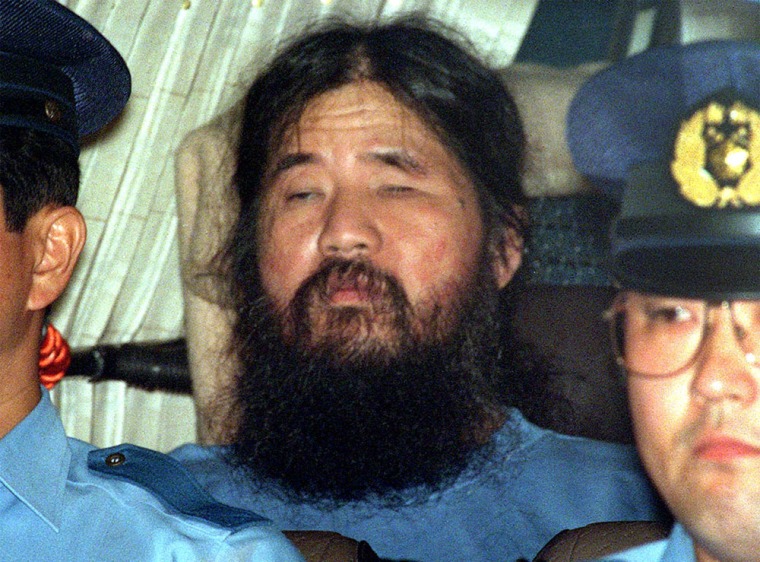

Former cult guru Shoko Asahara, accused of masterminding the 1995 nerve gas attack on Tokyo’s subways and amassing arsenals of chemical and biological weapons, faced a verdict Friday — and possible death sentence — on charges he ordered a string of crimes that killed 27 people, panicked Japan and alarmed the world.

Defense lawyers argued that Asahara, whose real name is Chizuo Matsumoto, had lost control over his Aum Shinrikyo cult by the time of the subway attack, in which sarin gas killed 12 people and sickened thousands.

But with abundant testimony of his responsibility from former cult members and Japan’s 99 percent conviction rate, a guilty verdict is widely expected. Eleven of Asahara’s followers have been sentenced to hang, although none has yet been executed.

Tight security

Friday’s court session opened with the reading of the reasoning behind the ruling — a process that could take hours before the verdict and sentencing are announced. Asahara grinned briefly as he was slowly led into the courtroom by guards.

Security was tight at Tokyo District Court to guard against attempts by Asahara followers to disrupt the proceedings. Some 4,600 people turned out for a shot at the 38 courtroom seats available to the public; spectators were chosen by lottery.

“I can’t think of any other sentence but death for Asahara,” said Yasutomo Kusakai, a 22-year-old college student who tried unsuccessfully to get a courtroom seat. “Many people were killed, and he’s supposed to be the mastermind of the crimes that affected the society in a big way.”

On Thursday, subway lines issued announcements urging riders to report any “suspicious objects.”

For families, a painful milestone

The verdict — which follows a trial that lasted nearly eight years — will mark a heart-wrenching milestone for the families of victims who have waited for justice for years, although they say the trial’s outcome will provide only limited solace. Asahara has the right to appeal.

Anti-Aum activists warned on Thursday that the cult, which has changed its name to Aleph, remains a potential danger because members have not rejected Asahara’s teachings.

“The cult is not reflecting on their crimes,” said Shoko Egawa, a journalist who has covered Aum since the 1980s. “They know nothing about the relation between the crimes and the teachings. I don’t think they want to.”

Egawa and Shizue Takahashi, the wife of a subway worker killed in the 1995 attack, also faulted police for failing to crack down on the cult sooner, despite evidence the group was a threat.

“I feel that the police have as heavy a responsibility as Aum Shinrikyo,” said Takahashi. She said she had considered suing the government, but thought the chances of winning compensation were too slim.

Sarin gas used

The March 20, 1995, subway attack was Aum’s most horrific crime. Five cult members pierced bags of sarin, a nerve gas developed by the Nazis, on separate trains in central Tokyo’s national government district.

Survivors still suffer from headaches, breathing troubles and dizziness. The cult was ordered to pay $35 million in damages to victims.

Asahara is also accused of ordering followers to carry out a sarin gas attack the previous year in Matsumoto, central Japan, that killed seven people; plotting the murder of an anti-Aum lawyer and his family; and killing errant cult members.

The subway attack shocked Japan, shattered its image as a secure haven from crime and triggered a long bout of soul-searching over its troubled youth. The gassing also was an early indication of how independent groups could use money and technology to build weapons of mass destruction.

Aum Shinrikyo a bizarre group

At its height, Aum counted 10,000 members in Japan and 30,000 in Russia. And after the subway attack, a crackdown on the group opened a window on its bizarre rituals.

Initiates paid hefty sums to drink Asahara’s dirty bathwater, sip his blood and wear electric caps to keep their brain waves in sync with their master’s. Drug use was rampant and people who challenged the group were attacked.

“They killed people at their compound, they destroyed people’s lives, they crippled people with their chemical attacks,” said David E. Kaplan, co-author of “The Cult and the End of the World: The Incredible Story of Aum.”

Aum’s weapons program was carried out by a coterie of highly educated scientists from Japan’s best schools. Asahara’s flock was bewitched by a mix of Hinduism, Buddhism and yoga that predicted an Armageddon that only cult members would survive.

Asahara’s trial was lengthened by Japan’s chronic shortage of lawyers and judges, the complexity of the case and a six-month delay when the former guru fired his first attorney.

Police say the cult’s remnants are showing signs of greater allegiance to Asahara. Agents this month raided the offices of the group, which still claims 1,650 members in Japan and 300 in Russia.