The problems that curtailed Thursday's planned six-hour spacewalk from the international space station have fully validated NASA’s justification for making what was widely considered an extra hazardous operation. Better by far to encounter a spacesuit malfunction now, after weeks of preparation, then during a crisis situation that required a quickly planned exterior sortie.

Instead of a real emergency, the crew was performing a "job jar" of spacewalk tasks for reconfiguring the Russian end of the station and setting up and dismounting various pieces of scientific equipment. These were all “nice to have” activities, and the trip outside was a big boost for the morale of the two crewmen, now two-thirds of their way through a psychologically challenging six-month space sojourn.

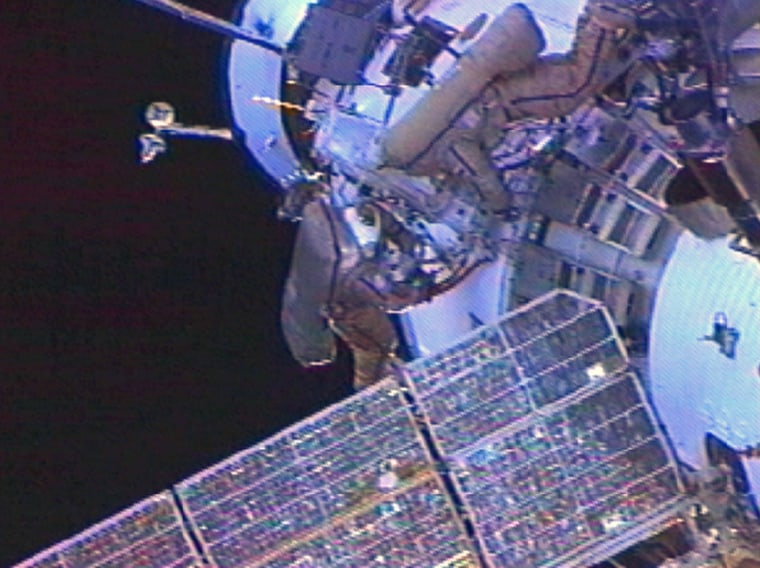

But halfway through the spacewalk, veteran Russian cosmonaut Alexander Kaleri startled Mission Control in Moscow with an announcement that he was having “full condensation” in his helmet. “It’s amazing. I have rain inside the helmet,” he said. Kaleri also noted a slight rise in suit temperature –- not hazardous or even particularly uncomfortable, but definitely an indication of a suit malfunction.

When the spacesuit didn’t respond to "contingency actions" to get the cooling system working again, Moscow called a halt to the spacewalk and told the men to get back inside. They had to tell American astronaut Mike Foale several times, in the end –- possibly because he realized that he, like senior cosmonaut Kaleri, was going to retire after the mission and so would never in his life be on a spacewalk again.

Initial indications are that the problem with Kaleri’s spacesuit don’t look connected with the cause of the “extra hazard” of the spacewalk -– the lack of a third person inside the station while the two men were outside. All station systems performed normally, and so did the airlock hatches. The only thing a third crewmember could have added was to take photographs through the windows.

The spacesuit cooling problem, while rare, is by no means unprecedented. At least half a dozen equally serious incidents have occurred over the past hundred or so Russian spacewalks, said space historian Jonathan McDowell, by day a scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and on his own time the editor of the highly-respected “Jonathan's Space Report.”

Aside from curtailed spacewalks in February 1992 and October 1993, McDowell pointed to a possibly “similar issue” with a suit thermoregulation failure on July 19, 1995, that prevented cosmonaut Anatoliy Solovyov from even leaving the airlock. Other problems cut short Russian spacewalks in February 1996 and April 1998 (a radio failure that time), and the previous Russian spacewalk had been abruptly terminated when the Mir space station’s stabilization computer failed and the station began drifting out of orientation.

Similar hardware problems -– as well as the ill health of scheduled spacewalkers –- have struck throughout the last forty years of American spacewalks as well. Despite the past history, this latest problem -- like any other malfunction in space -- shouldn't be minimized.

"I got the impression from the NASA TV coverage that the condensation from the problem was more than just an annoyance," McDowell said. It "sounded like after [return to the airlock], Kaleri could not read the dials on the Pirs pressure gauge due to faceplate condensation."

While the problem may have been a random failure that could have occurred with any spacesuit and any cosmonaut, the relative old age of Kaleri’s spacesuit will also likely be examined.

Although two new Russian-made "Orlan" spacesuits arrived at the station just last month, aboard a robotic supply freighter, Kaleri and Foale used the two older suits already on board. According to Viktor Blagov, deputy director of the Russian Mission Control Center, these two suits “were nearing the end of their certified lifetime”, and would soon be retired.

According to information obtained by McDowell, the suit Kaleri used –- serial number “M-23” – was originally sent up in July 2000, together with another suit that has since been retired and discarded. “M-23” was used eight times between mid-2001 and mid-2002; this was its ninth use.

“There was at least one Orlan on Mir used 10 times, so M-23 is not a record,” McDowell said. Nevertheless, it is significantly "used", as spacesuits go. During intense periods of spacewalks on Mir, some suits were used more than a dozen times each, but only within the first three years after launch.

"M-23 is now at 3 years 7 months," McDowell added, "a record." As such, it is the chronologically oldest Orlan spacesuit ever used on a spacewalk.

Foale’s suit, serial number “M-14”, was sent up in September 2001 and had been used only four times prior to this spacewalk.

At a NASA news conference prior to the spacewalk, space station operations integration manager Mike Suffredini was asked why the old suits were still going to be used when the new ones had just been sent up. He explained that the need to practice the emergency suited transfer from the Pirs airlock into the Soyuz spacecraft, through very tight hatches, had made the Russians unwilling to risk damaging one of the new suits by banging it against interior walls and doorways.

It was Kaleri, inside suit “M-23”, who twice performed this drill, first last November, then again a week before the spacewalk. Foale was in his suit only for the second practice session.

Although as of now there is no clear cause-and-effect between significantly banging up one of the oldest spacesuits ever used on a spacewalk, and that suit later malfunctioning, Russian engineers can be expected to examine that possibility carefully. The old suit is probably now going to be retired, and the crew will have to assemble and test one of the newly-arrived suits.

As Suffredini explained, both space agencies realize that spacewalks aren’t a luxury. They need to always have the capability to get the two-man station crew outside for an emergency repair operation within two weeks. This spacewalk’s overarching purpose was to demonstrate that capability or to uncover problems needing fixes, while there was still time to make the fixes.

And that means that this problem made the spacewalk even more valuable than if it had proceeded normally over its entire planned timeline. If a two-man spacewalk is ever needed in a hurry, the experience on this one will make it a whole lot safer.