School districts around the nation are being buffeted by turmoil and uncertainty, but nowhere are those forces more powerful than in this Mississippi River city.

At the heart of it, the turbulence is about dollars and cents and the quality of education. Fearing possible threats to its funding, the failing inner-city Memphis City Schools, with 209 schools and 108,000 students, decided to force a merger with its smaller, more affluent neighbor — Shelby County Schools.

To accomplish that, the district's board surrendered its charter in November. That unprecedented move, essentially undoing the creation of the Memphis district in 1869, was subsequently approved by the City Council and by the city’s voters in a referendum in March.

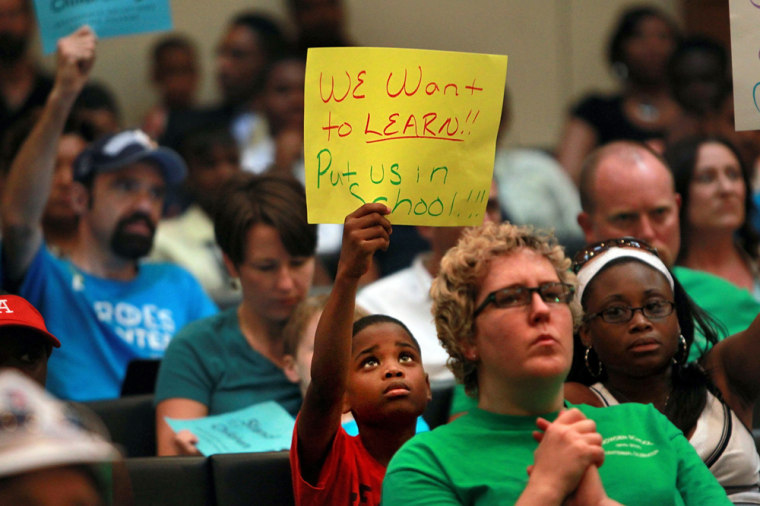

But while the move might make sense economically, it has triggered a heated debate about the fairness of merging two districts with different levels of academic achievement. It has even stirred the ghosts of the city’s legacy of busing students to alleviate racial inequities in the school system.

Residents of suburban Shelby County — in which the city is located — did not have a vote, and the county Board of Education sued to block the merger. Its chairman, David Pickler, refers to the unfolding events as part of a “hostile surrender” of his 47,000-student, 52-school district. A federal judge is expected to soon decide whether the merger will go forward and, if so, whether it would take place immediately or in the 2013 school year.

“It seems like there is a lot of distrust and a lot of fear on both sides, and of course the fear of the unknown,” said Talarescia Gillenwaters, a 41-year-old who attended Memphis schools and has two daughters in Shelby County Schools. She has conflicting feelings about the merger. “Until we really know what’s going to happen, I don’t know what we’ll do. We’re going to base our decision on what’s best for our daughters.”

The city district voted to disband after determining that a new Republican majority in the state Legislature could pass legislation long sought by Shelby County Schools to create a special school district, said Martavius Jones, president of the Memphis City Schools Board of Commissioners.

Such a district could create its own tax zone and potentially try to end its tax liability to the inner-city schools, he said.

That would have a disastrous impact on the Memphis district, Jones said, noting that the suburbs contribute about 49 percent of the county’s residential property tax base — which helps fund both school districts — while accounting for some 28 percent of the population.

Pickler denied Shelby would take such action or that equitable county funding for the districts would be jeopardized, adding that winning the special status was not part of the district’s legislative agenda this past year.

Jones said city dwellers helped fund the county’s growth over the decades by paying for schools and other infrastructure, allowing suburbanites to “prosper and enjoy their standard of living.”

“I feel that we have just as much right to the schools that happen to be outside the city limits of Memphis because our funds built those schools, too,” he said, noting that it would be a “selfish act” for those in the county “to try to live in a walled environment.”

The two districts can have a fresh start, Jones noted: “We can be a shining example of how to do public education right.”

In pursuing a merger, Memphis school officials are making the same kind of tough choices facing public school districts around the country, as many recession-battered states cut education funding. Economic data released last week has renewed fears that recovery could soon slip back into recession.

At least 34 states and the District of Columbia have made cuts to K-12 education since 2008, according to the Washington think-tank Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

“School systems everywhere have cut to the bare bones,” said John Musso, executive director of the Association of School Business Officials International. “School districts have taken the low hanging fruit, the very simple obvious things you do like the energy savings kind of thing, but they’re at the point now where you’ve got instructors who are gone, we’ve got class sizes that have increased.”

One way of doing more with less is consolidating school districts, an option that's also under consideration in Vermont, Indiana and Arizona.

The renewed interest in consolidation continues a long-term trend in education, said Musso. In the 1940s and 1950s, there were about 120,000 school districts, while in 2008, the number was 15,000, he said.

“We haven’t seen consolidation for quite a while,” he said. “It’s slowed down until right about now, but there are some consolidations going on just because of the economy.”

Dan Domenech, executive director of Virginia-based American Association of School Administrators, noted that the situation in Shelby County was “a reflection of the inequities in how education is funded” nationwide.

“What you have is a typical situation in Memphis, which is an inner-city school system with a greater percentage of children on free and reduced lunch, more poverty, while Shelby is a more typical suburban middle-class community that is better funded and consequently tends to have what is regarded as a better quality educational system,” said Domenech. Memphis “wants to ally themselves with a community that has greater resources in the hopes that that will elevate … the quality of schools.”

Adding to the Memphis City Schools concerns this year was a backlog in funding from the City Council dating to 2008, when the council approved a property tax cut and slashed $57 million from the school system’s annual budget. The school board sued and won, but the cash-strapped city had not yet repaid the shortfall. The two sides reached a deal Tuesday, so school should begin as planned on Monday, The Commercial Appeal reported.

About 23 percent of residents in the city — home of the late Elvis Presley and his Graceland mansion — lived below the poverty level in 2008, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Memphis’ economy also has been slow to recover from the recession, with foreclosures, a decline in tourism and the lack of a substantial high-tech sector slowing progress, The Commercial Appeal reported recently.

Shea Flinn, a member of the Memphis City Council, said the city is trying to increase its tax base by luring businesses and new residents but faces stiff competition from the suburbs and the likes of Nashville, where the local tax burden is half that of Memphis.

Still, though the troubled economic times were a factor in the district merger, it was not the key driver, he said.

“I think the primary motivation was to take ... a leap of faith if you will,” he said. “This is a unique opportunity to build a brand new best-practice-driven urban school system, and you’re just not going to get that opportunity a lot, and you shouldn’t walk away from it.”

But Pickler cautioned that a merger could create “educational chaos.” The districts have different philosophical approaches to education as well as separate vendor deals and how they handle teacher contracts — all of the nuts and bolts of running schools.

He also decried creating a “mega-district,” saying it could hurt student achievement and parent involvement.

Ken Hoover, who has three children in the Shelby County Schools and owns an Internet software business, shares those concerns. He opposes the merger and has formed a committee with other parents to explore setting up a small municipal school district.

“Suburban residents oppose this merger because you’re taking the management team that has delivered 3 ‘F’s and a ‘D’, and putting them in charge of a school district that has delivered four ‘A’s, straight ‘A’s,” Hoover said, referring to the Tennessee Department of Education’s report card for schools.

The heated debate over the merger has raised the specter of busing in a city where it was ordered to desegregate schools following the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision to end “separate but equal” schooling.

Domenech said the current initiative by Memphis was based on the same principles, though along economic rather than racial lines.

“I think it’s communities looking for the quality of education that they feel their kids ought to be getting, looking across on the other side of the fence and seeing that that grass is so much greener and, you know, wanting to take advantage of that,” he said.

But lawyers representing the city in the legal battle over the merger added to the distrust over the suburban district’s motives by arguing in a legal brief that the Shelby board had demonstrated a "consistent and ongoing resistance to racial balancing of the public schools in this county.”

Pickler denied race was a factor in his district’s opposition and noted that over the years the student body has reached parity between the number of white and minority students.

“I believe that we are more segregated in Shelby today than we have ever have been but it’s not based upon race, it’s based upon socioeconomics and that is a dramatic situation,” he said. “… People in this community, if they have the economic opportunity to migrate, they have been pursuing that.”

Chris Caldwell, who has three children in Memphis City Schools and is a member of local education nonprofit Stand for Children, said the consolidation offers an opportunity to even the playing field.

“I think there’s been misconceptions in both the black and white community about each other, and that’s been some of the history of Memphis,” said the 58-year-old investment broker. “And if they could see that this wasn’t … ‘gloom and doom’ … that these kids can get along,” the city could go “very far toward meeting its potential.”

Chris Lareau, who supports consolidation and whose daughter attends a Memphis school, agreed that the dispute has nothing to do with race. Parents just want a “fair source of funding,” he said.

“This is not an us-versus-them story,” said Lareau, a prosecutor in the Shelby County District Attorney’s Office and also a Stand for Children member. “This isn’t selfish white folks out in the suburbs … just wanting to abandon … poor African-American kids. … This story is about bringing Memphis into the future and being progressive with our city and saying, ‘Hey, listen we are one community, there is one Memphis and we are going to have one source of funding for all of our schools.”

Follow @mimileitsinger