A girl makes mud pies in the dirt, a toddler takes wobbly steps in the grass, a boy picks blueberries and another builds a snowman.

Those are simple pleasures in Oregon, but not for the children of Fukushima, Japan, where a nuclear disaster in the wake of the March 11 earthquake and tsunami forced them indoors for months, required them to wear protective gear when they did venture outside — even made them wary of plants, grass and rain.

At least 11 kids and their parents, refugees from Fukushima and other parts of Japan, are visiting Oregon this month and living with U.S. host families as part of a grass-roots effort to give them a break from the stress and health risks they had been facing at home.

But as their brief respites draw to a close, their thoughts are already on the trip back home and what their next moves will be.

“I felt it was necessary to get away from that place where we had a really scary experience, and watch my son feel better and more alive,” Yoshie Arai, 37, who came to Oregon with 10-year-old Tatsuki in late July, said through a translator. “That made me feel sure it was a good decision. But this trip has made me feel really strongly that maybe going back — that’s not really the place to live. … I want to seek other alternatives.”

More than 46,000 people living in Fukushima Prefecture have left since the triple disaster, the Mainichi Daily News reported this month, in English, citing local government data.

Among them were nearly 7,700 students, with another 1,100 planning to do so during the ongoing summer break, the newspaper quoted education officials as saying. Of the latter, 75 percent were leaving because of radiation concerns.

Worries about the impact of radiation on their children also were paramount for the mothers who brought their families to Oregon.

The government told them daily that there was radiation but not about how it could affect them — just that it wouldn't right away, Mayumi Abe, who traveled to the U.S. with her 3-year-old daughter Karin, said through a translator.

They were told, “Oh, if you worry about it, you can put a mask on and you can kind of wipe yourself off right before you go inside,” she added.

Another mom, Mayumi Fujimori, recounted the horror of learning her 8-year-old daughter, Remika, and other kids had been playing outside when the first reactor exploded at the plant, which eventually suffered meltdowns or partial meltdowns in three of its reactors. Later blasts released radioactive substances into the air and allowed contaminated water to leak into the ocean.

“Something really terrible, something really unimaginable happened,” Fujimori said through tears, noting she only found out about the blast hours after it happened. “I didn’t know what to do and how I could protect my children. I tried to do my best.”

Children under the age of 18 are most sensitive to the effects of radioactive iodine, one of the main isotopes released during the disaster, according to the Centers of Disease Control.

Researchers on Saturday released a study showing that low levels of radioactive iodine had been found in the thyroid glands of children from Fukushima, Japanese broadcaster NHK reported.

The low levels found in about half the children suggest it is unlikely thyroid cancer rates would rise in the future, but health checks should continue, said Satoshi Tashiro, a Hiroshima University professor who led the study of 1,149 children.

The local government will conduct two health screenings for Fukushima prefecture residents through October, Morikuni Makino of the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency wrote in an email to msnbc.com.

In addition to basic health checkups, health-care workers will estimate radiation exposure dose based on food consumption, conduct ultrasound tests on the thyroids of children and teenagers, and perform mental health evaluations. An individual health check specific to pregnant women would also will be conducted, Makino said.

In the last month, radiation levels have reached record highs at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, said its owner, Tokyo Electric Power Company, and more than 1,000 cattle were found to have eaten feed contaminated with radioactive cesium, news agencies reported.

The announcements have stirred greater fears among the Fukushima mothers, some who said they don’t want to go back there.

Arai, whose son has suffered nightmares, nose bleeds and fevers that she attributes to stress, said she had planned to quit her job at a real estate firm before coming to Oregon, but they told her she should just take some time off.

But further reflection hasn’t changed her mind. Arai said she doesn’t think Fukushima is “going to recover to the point that I’d like to see. I don’t think it’s a place for children to live.”

Chifumi Brown, a Japanese-American therapist who is hosting the Arai family, is holding a weekly informal therapy session for the mothers.

“They’re really in the survival mode of needing to get away,” she said.

They need “a breath of fresh air, literally,” Brown’s husband, Christopher, later added.

The families connected with each other through “Boshi sokai-shien network hahako”, a network set up days after the disaster struck by Yuko Kida, a part-time English teacher living in southern Japan who wanted to help out families looking to escape Fukushima.

The name of the network means “mother-child,” Kida explained, noting that pregnant women and babies are most vulnerable to radiation.

“We didn’t know how bad the impact of the nuclear plant’s accident (would be), but we could imagine maybe it will be very, very bad,” said Kida, a 45-year-old mother of two.

To date, about 45 families from countries such as the U.S., Australia, Britain, Thailand and Malaysia have offered to host families, with another 500 to 600 offers from elsewhere in Japan. A few hundred Japanese families have been placed with host homes so far.

The network also has now expanded – it’s called “Sokainowa” or “ring of evacuation” — to include support groups from throughout Japan.

Ten families were expected to travel to Oregon this year, said Camellia Nieh, a Japanese language interpreter and translator who organized the local effort.

Nieh said she was motivated to bring the families over to give them physical and emotional breaks, “so that they can go back with ... renewed energy.”

See msnbc.com's series on post-tsunami "Japan: After the Wave"

The Japanese families — they came without the fathers — paid their airfares and made arrangements with the host families to cover their daily expenses, such as food.

“I wanted to do something directly, not just donating the money to some organization. I just really wanted to do person-to-person … help,” said Kurumi Conley, a Japanese-American glass artist hosting the Fujimori family in her home with her husband and two daughters.

Abe, the mother of the 3-year-old, said the stay with their host family was critical to their mental health.

“I was trying to control all of that stress and emotion,” she said.

She felt guilty about taking Karin outdoors back home and said that “just to be able to go outside is a huge thing,” noting her daughter had even asked her if plants were OK to touch in Oregon since back home she could not.

“I wanted my daughter to have a summer, to be able to go outside, and so I started looking abroad,” she said as she became teary-eyed.

She later added that her trip has been full of tears over the memories of “just really simple things that I was able to do, that I used to be able to do.”

With their host family, they’ve visited a gorge, walked on Mount Hood where Karin made a tiny snowman and visited Portland’s Japanese Garden. The Arais have gone blueberry picking, and Tatsuki said his favorite activity was bike riding with his hosts.

When asked what he can do here that he can’t back home, Tatsuki said: “I can open the window and I can also wear short sleeves and short pants.”

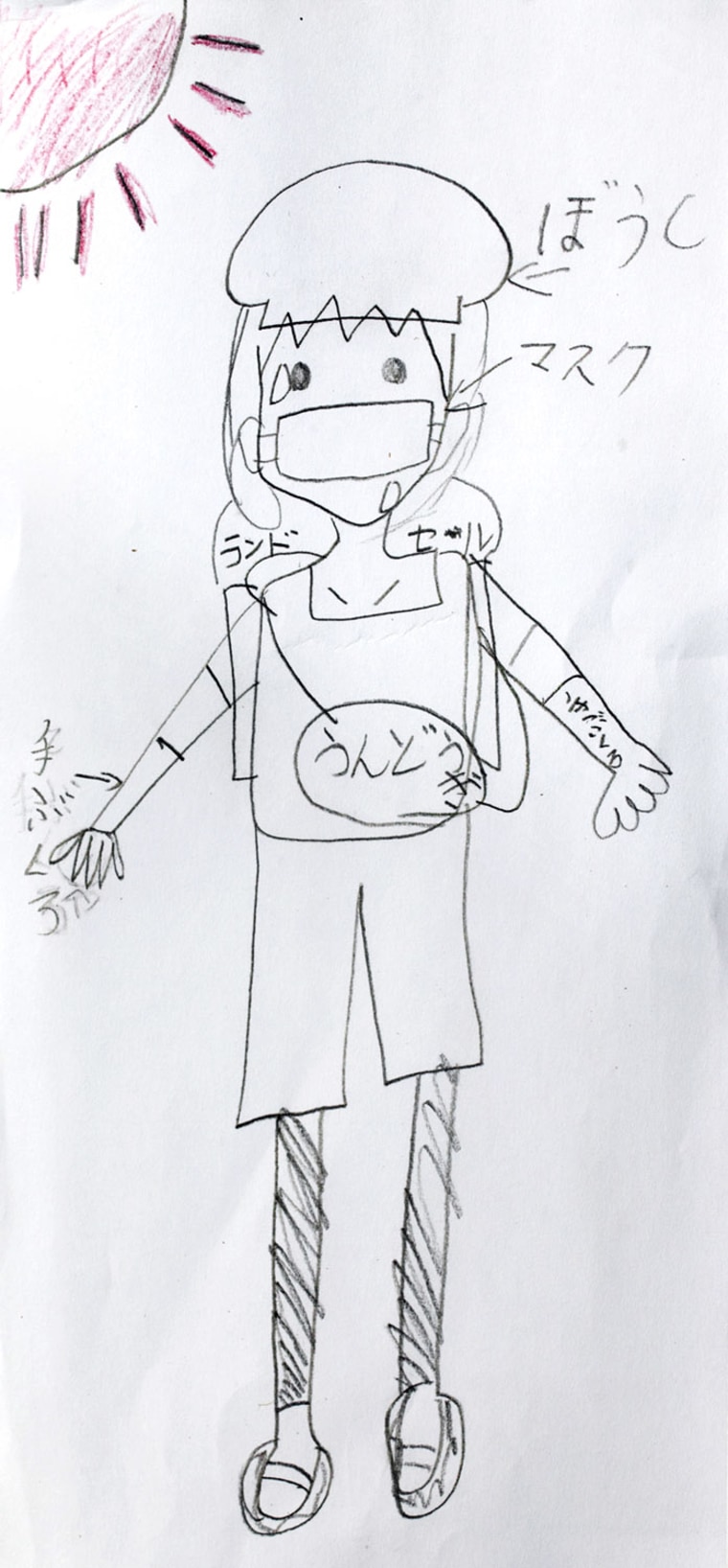

Fujimori’s daughter, Remika, drew a visitor a self-portrait showing what she had to wear to school after the disaster — a mask, leg coverings and gloves, and a hat — to protect against possible radiation contamination.

When asked about how it was to wear the gear and why she depicted herself under a red-colored sun, she said: “It’s hot.”

Fujimori said she and her husband used money they were going to spend on fixing quake damage to their home for the U.S. trip, and she’s glad they did now that her daughters can “play outside, walk around barefoot, drink good water, eat delicious vegetables and fruit.”

“My younger daughter gets to play outside for the first time,” too, she added, as her 15-month-old daughter played with flowers and practiced walking through their host family’s backyard.

Not all of the visiting families are from Fukushima. Wakana Koshio came with her two boys from the Katsushika-ku ward of Tokyo, which has been labeled a local radiation “hotspot” by the grassroots monitoring network Safecast. She read books on radiation and scoured the Internet for information.

Koshio said she felt at one point like she “failed to be a good mother,” believing she wasn’t able to protect her youngest son, a 2-year-old, from any risks.

“If you weren’t working then you could just fly away anywhere, but I couldn’t do that,” she said through tears. It was hard to get a month off from her job as a sales assistant, she said, “but still I thought I should put my children first.”

Koshio and the Fukushima mothers expressed resentment at how the government handled the nuclear crisis and recounted trying to wrangle information out of authorities.

“I don’t think the government is doing enough, but I’m not really much counting on them. I have no expectation. I’m more looking for support from the community,” Arai said.

Financially, it would be hard for them to move, as others had done, the mothers said. But though things in Fukushima will never be the same, Abe said the U.S. break had given her a new resolve to confront the challenges she and the others will face when they soon head home.

“I think this made me stronger,” she said. “Coming here has actually refreshed me … and this really helped me to look ahead.”