When conservationists decided to fight for the wetlands, they called in their big gun.

Perched at President Bush’s elbow for an hour-long White House meeting was John Tomke, president of Ducks Unlimited, the nation’s largest waterfowl hunting group with 1 million members.

It looked like a cozy gathering. George W. Bush’s father is the organization’s most celebrated member since John Wayne. When you telephone its headquarters, you’re likely to hear a recorded message by the former president instead of Muzak.

But this meeting was no social call.

Twenty-million acres of fragile wetlands across the United States could be bulldozed by developers because of the administration’s plan to rewrite fine print in the Clean Water Act.

Booming coastal communities and ports are especially vulnerable. In fun meccas like Myrtle Beach that now command premium prices, a quarter of the lowlands in the area could be affected.

Wetlands are vital to maintaining water quality, as well as habitat for nearly half of the nation’s endangered species. Traditional conservationist groups knew they couldn’t shoulder their way into this Oval Office over the plight of swamp-dwelling salamanders and songbirds.

But ducks! Now those are wetlands birds with political muscle.

Bush backs off on rule

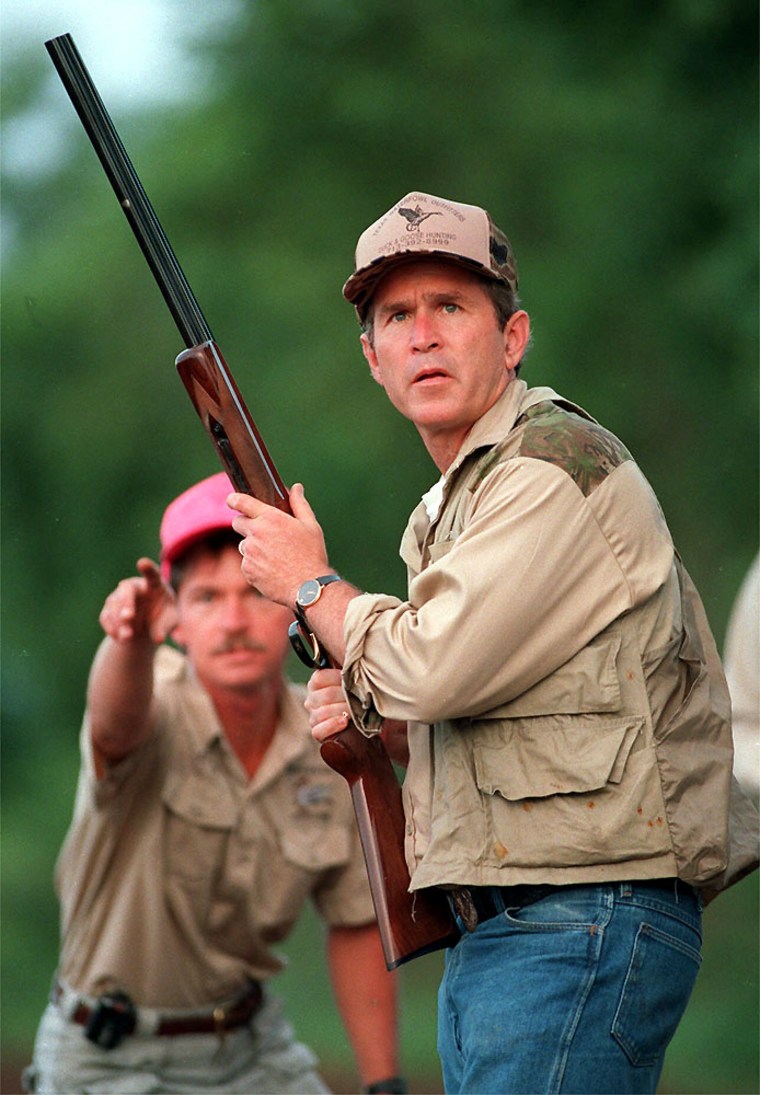

So the tree-huggers awkwardly linked arms with the hunters for their White House visit in December. The president leaned over to tell Tomke how much he enjoys hunting on the Texas Gulf Coast, where green-headed mallards and pintails flock every autumn.

Tomke, in turn, reminded Bush that 22,000 hunters were among the 133,000 Americans who filed protests to his wetlands plan. Along with 218 congressmen, including 26 Republicans.

Out on the marsh, a man’s prospects can be shattered in a single phrase: “I wouldn’t share a duck stand with him.”

Four days later, the administration announced the president had personally decided “not to issue a rule that could reduce” federal wetlands protection, including smaller parcels important to wildlife called “isolated” wetlands.

Happily ever after?

Not exactly.

Since the December meeting, conservationists say isolated wetlands development continues at an ugly pace. Many of the projects already were in the works, some reaching back to previous presidents.

More disturbing, the wetlands supporters say, is that field inspectors for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other agencies still appear to be following the administration’s preliminary orders — known as “guidance” — not to interfere with development in isolated wetlands.

“Guidance is where mischief often occurs,” says Nancy Vinson of the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League.

Controversy over what's a wetland?

Wetlands by their very nature are as difficult to define as they are to walk through — alchemies of water, earth and mist. The Southeast has the largest variety, with evocative names like pocosin, citronelle pond and Carolina bay.

But isolated wetlands are rooted more in law than science. Federal agencies describe them as low-lying areas surrounded by dry land without — and this is crucial — a direct surface connection to a waterway.

Biologists contend nearly all wetlands have important hydrological connections, even if they are underground and out of sight.

“The sort of isolation being described is a political concept,” writes Allen Plocher of the Illinois Natural History Survey.

Isolated wetlands are particularly vulnerable. They tend to be small, inconspicuous. Because they are not monumental landscapes, their loss doesn’t ignite the kind of public outcry like the one over, say, Bush’s plan to drill for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

But even little, isolated bogs perform the same work as larger swamps that obviously feed rivers and lakes and remain regulated.

Operating as “nature’s kidneys,” they sop up hurricanes and floods, recharge aquifers, filter pollution and trap sediment. They provide wildlife habitat and contribute to the nutrient cycle.

In South Carolina, scientists calculate that for every wetland acre that is paved, coastal estuaries that nourish marine life lose 7.6 pounds of dissolved organic carbon.

“If you want to have shrimp to eat, you need wetlands,” says Prescott Brownell, a biologist for the National Marine Fisheries Service, a federal agency.

Supreme Court stepped in

Thirty years ago, all wetlands received broad protection under the Clean Water Act.

Development wasn’t prohibited. But dredge and fill permits were required and projects could not harm the “nation’s waters.” Developers complained they were straitjacketed by red tape protecting some isolated “puddles” that nobody would miss.

Then in a 2001 case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the Clean Water Act could not block Chicago-area governments from turning an isolated wetland (a flooded rock quarry, actually) into a landfill because the wetland didn’t nourish interstate waterways.

Quickly, the Bush administration extended the rationale nationwide.

Since most states do not have their own wetlands laws, the remaining small, isolated wetlands were exposed.

In South Carolina, for example, at least 300,000 isolated wetland acres are believed to be vulnerable along the coastal plain since the court’s 2001 ruling.

Scientists consider these soggy bottomlands to be among the nation’s richest ecological treasures, bubbling kettles of evolution for birds, rare amphibians, even flesh-eating plants. They were hidden in thicket forests that timber companies harvested for decades, but otherwise they were ignored.

Then in 1989 Hurricane Hugo slammed into Myrtle Beach. In the flurry of building that followed, the resort city added oceanside golf, casino boat gambling, outlet shopping, even a Hawaiian “volcano.” Inland, rows of tract housing are still sprouting like pine trees in a plantation forest on streets with names like Marsh Glen Drive and Spotted Owl Landing.

Home Depots and Wal-Marts perch like citadels on naked mounds surrounded by moats. Just weeks ago those sites were teeming marshes, and they’re still bleeding blackwater.

Biologist Brownell is a South Carolina native who has spent his life bushwhacking through the Low Country in rubber boots. He calculates that it takes just a year or two for heavy machinery to obliterate vast wetlands that flourished in the 20,000 years since retreating Ice Age glaciers contoured this coast.

His deep, courtly voice drips like syrup, but he can’t conceal his contempt.

“First they cut ditches to dehydrate the land,” Brownell complains. “Then they take a machine that chops up all the native shrubs and groundcover. Then they say, 'No wetland here!”’

South Carolina controversy

One project is particularly galling: the Carolina Bays Parkway, named after a peculiar Southern wetland that used to be common here.

The six-lane, $231 million bypass should reduce Myrtle Beach traffic by slicing through gurgling cypress and tupelo swamps. The state highway department and its contractors got federal permits to fill 223 acres of wetlands along it.

But conservationists say more wetlands were destroyed illegally along the route. The epicenter of the dispute is a 65-acre roadside crater. A parade of dump trucks haul gravel and fill dirt from this “borrow pit” for construction elsewhere.

Federal inspectors determined the site was an isolated wetland, thus fair game for the contractors without a permit. Opponents contend the parcel drained into the nearby Waccamaw River.

The Southeast Environmental Law Center, representing several groups, has filed notice that it intends to sue.

The “borrow pit” is the most obvious example what SELC attorney Blan Holman contends is rampant unpermitted development.

“I could find 10,000 acres of wetlands that have been recently destroyed,” Holman said. “Something is seriously broken here.”

Other states

Development threatens beyond this state. In Minnesota and Wisconsin, at least 3,800 isolated wetlands have been slated for development.

In New Mexico, federal documents suggest 20 percent of that arid state could be declared an isolated basin, said Julie Sibbing of the National Wildlife Federation, a Washington-based interest group. That would strip protection from 3,400 miles of streams that carry water only a few months a year.

What’s more, agencies largely have stopped keeping records of isolated wetlands cases because they have stopped overseeing them.

“It is our worst nightmare,” said Sibbing, who complained it’s impossible to find out what areas are being developed or protected.

For example, the Corps’ district office near Houston told her there are no documents showing the status of more than 1,000 acres of wetlands at the site of a planned major container and cruise ship port on Galveston Bay. Environmental groups have sued to stop the project, despite an offer to protect different wetlands in exchange.

Field inspectors say wetlands have become their biggest headache. Usually they get one chance to visit a site. Most of their decisions are appealed.

“I think the Corps’ role is to ensure that no party is happy,” said Corps senior project manager Richard Morgan in Savannah, Ga.

Wildlife and humans

Everyday since 1978, researchers have been studying one isolated wetland near the Savannah River, and they’ve found it is a fertility fountain.

In 26 years, they’ve caught and counted over 1 million amphibians and reptiles in bucket traps representing 66 species. Species such as: ornate chorus frogs, narrowmouthed toads and an array of salamanders — tiger, mole and marbled.

Last year from February through May, they captured 273,000 amphibians and 410 reptiles. On a single night, they captured 12,000 metamorphosing juveniles.

Some species, like wood frogs, require several generations to move a single mile, often slithering and hopping from one bog to the next. If small wetlands were removed without ecological consideration, scientists who study these species say local extinctions would be likely.

But politicians and supporters of growth point out that wetlands development has brought a different kind of vitality to places like Myrtle Beach.

Tourism has surged to 13 million annual visitors. Retail sales have tripled to $7 billion. Voters have rejected zoning and density restrictions, building permit quotas and impact fees, lest they burst the bubble.

The stakes are high. About the same time President Bush was talking duck-hunting with Tomke, local officials learned they were $2.8 million short in bond payments on a staggering $1.2 billion road construction plan, including the new Carolina Bays parkway.

Their solution: refinance the terms through 2017 through even more development.

Out on the marsh, hunters remain wary about the future of the wetlands here and elsewhere. For now, they say President Bush is welcome to share their duck stand.

“The administration must make sure the federal rules continue to protect isolated wetlands,” said Don Young, a Ducks Unlimited leader. “We can bring our energies to bear again if need be.”