In the wake of Feb. 26's dramatic spacewalk from the international space station — a walk cut short by a cooling problem in one of the Russian spacesuits — new questions have surfaced about whether the walk was really as safe as NASA insisted, and about how much information about the suit problems was shared between the Russian and American partners.

There is now evidence that at the very beginning of the spacewalk, NASA broke one of its safety rules to prevent a delay. Further, there are suggestions that specialists at Russia’s Mission Control Center were aware of problems with the malfunctioning spacesuit hours before NASA and the rest of the world learned of them.

These two issues appear to be entirely unrelated, but together they paint a picture of a NASA still too ready to take risks, and of a Russian partner still too unwilling to share their insights into safety issues.

"I'd be bemused if I wasn't concerned," a former member of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board who asked not to be named told MSNBC.com.

Commenting on NASA's compliance with safety rules for extravehicular activity, the former board member said: "NASA didn't convey any immediacy for this EVA, I can only surmise that their proceeding and breaking their own rule could be indicative of yet another perceived schedule pressure, plus a continuing culture of waiving established rules."

Elaborate set of procedures

Thursday's outing was the first-ever spacewalk from the international space station that left no crew member aboard. In recognition of the risks, NASA and the Russian Aviation and Space Agency developed and tested an elaborate set of backup procedures. And to aid in real-time decision-making, space experts in both countries drew up flight rules that included a "Minimum Equipment List," defining which hardware must be working in order for the spacewalk to proceed safely.

But now it appears that NASA officials went ahead and violated one of the prime rules — the requirement for redundancy of remote monitoring of breakdowns — to allow the spacewalk to proceed, even after breaking the rule concerning what NASA calls “Caution and Warning” capabilities.

NASA’s internal "On-Orbit Status Report" for Saturday states: "When [Service Module] panel power was turned off during EVA prep[aration]s, the PCS [portable computer system] laptop in the SM was also deactivated, which was in violation of a flight rule and the EVA-9 Minimum Equipment List.” This appears to have been the result of an incorrect configuration radioed up from Earth, which led the crew to connect the computer to a plug that they erroneously expected to remain “hot” even when a nearby control panel was turned off.

As the document explained, “the flight rule requires a minimum of two active PCS's attached to core data busses for Caution & Warning support.” That is, there must be two separate ways — a prime and a backup path — for a crew returning from a spacewalk to immediately see a time history of any alarms (such as a fire, leak or short circuit).

The reason for this requirement is that with nobody inside during the spacewalk, any serious problem would require immediate termination of the spacewalk — and the returning crew would need immediate information on what measures must be taken to counter the emergency. There are very few specific “display consoles” and dedicated CRTs on the ISS — almost all communication from and to the control computers are through portable laptops.

So if only one laptop was left on, and the emergency situation — perhaps power, perhaps computer systems, perhaps communications — also crippled that one laptop’s display, the crew would rush back inside to handle a critical problem — and be unable to recognize the nature of the problem.

Violation deemed acceptable

But the rule was then deemed unnecessary. “After coordinated evaluation/assessment of the situation by [Houston] specialists, including the [Mission Management Team] Chair, the violation was deemed acceptable, and EVA ops continued as planned,” the status report explained.

The Mission Management Team is the group that oversees the operation of the flight director and the team of flight controllers in the Mission Control Center. It was in this kind of meeting during the flight of Columbia last year that NASA officials decided potential hazards to that flight could be disregarded.

After the Columbia investigation, NASA vowed to increase safety awareness and institute closer oversight of future Mission Management Team deliberations.

In this case, one of the NASA officials explained privately to MSNBC.com that “the consideration was that we had near-continuous [radio link], so we could monitor and take action on Caution and Warning." But NASA veterans told MSNBC.com that such a move should have been debated during the development of the flight rules, not as an afterthought.

NASA’s status report ended its discussion of the incident with the upbeat assertion that “the [computer] was successfully reactivated following the spacewalk." But once the crew was back aboard the station, the explicitly documented need for two computers was no longer in effect.

Cooling system problem

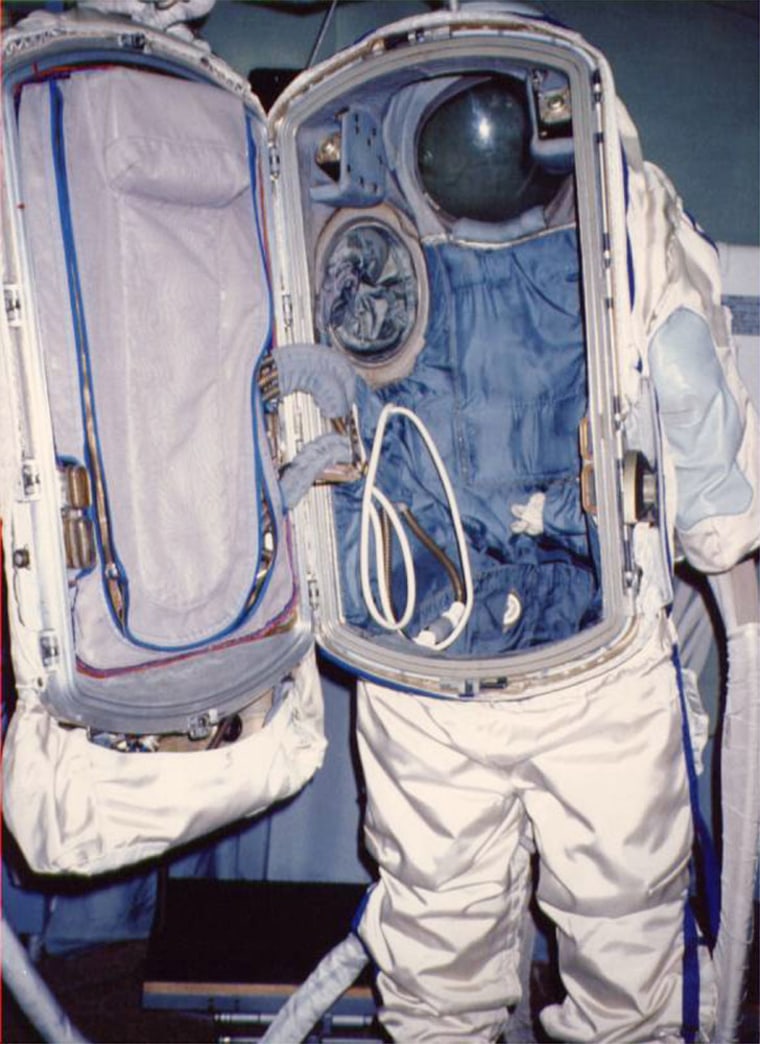

The crew was back aboard the station after four hours, instead of the planned six, due to a problem with the cooling system in the spacesuit used by Russian cosmonaut Alexander Kaleri. It turned out that one of the suit's coolant lines was kinked.

According to a NASA status report published the day after the outing, “the walk was proceeding smoothly and problem-free for almost three hours until Kaleri reported that drops of water were beginning to form inside his helmet visor.”

But the same day, a different version appeared in the Russian news media. A TV correspondent for Moscow’s Channel 1, Ivan Yevdokimenko, said “the fact that Alexander Kaleri’s spacesuit was not cooling off properly was spotted by Mission Control minutes after the spacewalk began.”

NASA told MSNBC.com not to believe Yevdokimenko’s story.

“This account is wrong,” NASA spokesman Rob Navias said in response to an e-mail query Friday morning. “We reported the cooling issue immediately.”

It does seem that the cooling issue had not been brought to NASA’s attention until Kaleri mentioned it on the air-to-ground radio link; only at that point did NASA, at last aware, release the information.

What did they know, when did they know it?

During a Friday afternoon telephone press event, NASA’s lead spacewalk controller for the mission, Michael Hembree, passed on what he had later learned about this communications lapse. Russia's lead spacewalk expert in Moscow had conferred with his own specialists after the spacewalk, and according to the account Hembree had heard, “they were monitoring the outgoing temperatures in the [cooling system] and they were higher than expected.”

As a result of these readings, they requested several times that Kaleri be asked how he was feeling, but without explaining their reasons. When the cosmonaut did not report being overheated, they took no further action. Since the Russian side was in charge of the spacewalk and there seemed to be nothing going wrong, NASA had not been informed of the worrisome telemetry measurements.

When NASA's space station managers discussed the shortened spacewalk with journalists in a Friday telephone briefing, they said they were puzzled about when and how the coolant tube had kinked. Michael Suffredini, the operations integration manager for the station program, could not explain how the water cooling line could have started off in working order and then gotten kinked halfway through the planned six-hour spacewalk.

On Monday, Russia's Itar-Tass news agency quoted spacesuit engineer Gennady Schavelev as saying that the coolant hose "might have bent while the cosmonaut was putting the spacesuit on."

Like the Russians, American space engineers who have talked privately with MSNBC.com consider it much more likely it had been crimped from the time Kaleri put the suit on. This would account for the anomalous temperatures noted in Moscow early in the spacewalk — hours before Americans were made aware of the problem.

Questions to be answered

Suffredini asked for patience while the incident is being investigated.

“What crimped the hose is still a question to be answered,” he stated. “We don’t know the mechanism of how the line can get kinked, or get kinked intermittently. ... The line is designed not to kink.”

Suffredini stressed that there was no health concern for the crew. “Never was there any time that the crew was at risk,” he told reporters.

But by setting aside a newly endorsed flight rule, and by remaining uninformed about the Russians' spacesuit concerns for almost three hours, the NASA team may have run unnecessary — if slight — additional risks. In hindsight, and in light of how those attitudes contributed to the shuttle disaster a little more than a year ago, it looks like a little more soul-searching of the NASA “safety culture” is called for.