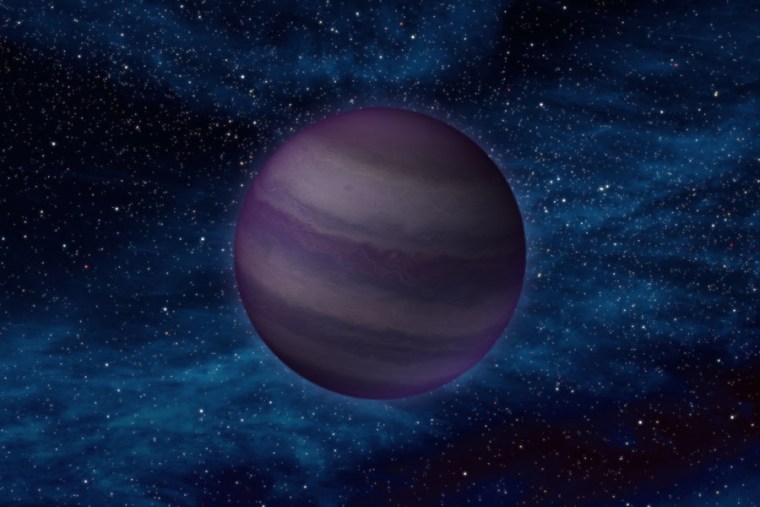

Scientists have discovered the coldest type of star-like bodies known, which at times can be cooler than the human body.

Astronomers had unsuccessfully pursued these dark entities, called Y dwarfs, ever since their existence was theorized more than a decade ago. They are nearly impossible to see relying on visible light, but with the infrared vision of NASA's WISE space telescope, researchers finally detected the faint glow of six Y dwarfs relatively close to our sun, within a distance of about 40 light-years.

Y dwarfs are the coldest members of star-like bodies known as brown dwarfs, which are odd objects sometimes known as failed stars.

Brown dwarfs are too puny to force atoms to fuse together and release nuclear energy, and so they have only the little heat they were born with. This heat fades over time until all the light they do emit is at infrared wavelengths.

So far, WISE has helped find 100 new brown dwarfs.

The coldest 'failed stars'

To see how cool the coldest of these Y dwarfs was, the researchers used NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to analyze its pattern of light. They found this coldest Y dwarf, known as WISE 1828+2650, was colder than 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

"The brown dwarfs we were turning up before this discovery were more like the temperature of your oven," said astronomer Davy Kirkpatrick, a WISE science team member at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and lead author of a study on the 100 new brown dwarfs. "With the discovery of Y dwarfs, we've moved out of the kitchen and into the cooler parts of the house."

The closest of these Y dwarfs, WISE 1541-2250, is 9 light-years distant. In comparison, the alien star closest to us, Proxima Centauri, is about 4 light-years away.

"Finding brown dwarfs near our sun is like discovering there's a hidden house on your block that you didn't know about," said astronomer Michael Cushing, a WISE team member at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and lead author of the study on the Y dwarfs. "It's thrilling to me to know we've got neighbors out there yet to be discovered. With WISE, we may even find a brown dwarf closer to us than our closest known star."

The coldest brown dwarfs until now were the T dwarfs, which get as cool as about 440 degrees Fahrenheit. First uncovered in sizable numbers in the late 1990s, the dwarfs led astronomers to ask whether there could be dwarfs even cooler, Kirkpatrick told Space.com — for instance, ones that might be older and thus with more time to cool off, or less massive and with less heat to begin with, or both.

Classifying brown dwarfs

Scientists name stars and brown dwarfs based on their temperatures, "with 'O' stars being the hottest, and now 'Y' dwarfs being the coldest,'" Cushing explained.

Most of the letters of the alphabet already have strong associations with other astronomical objects, so "after eliminating these 'used' letters from consideration, there are really only a few left, and those are H, Y, and Z," Cushing added. "Since Y comes after T, we felt it was the appropriate choice. Using Y also leaves room for an additional 'Z' class if astronomers discover even colder objects."

Better understanding Y dwarfs could shed light on how stars and planets form.

"Brown dwarfs in general, and Y dwarfs specifically, are a wonderful bridge between stellar and planetary astrophysics, because we think brown dwarfs form like stars, but in many respects look more like gas giant planets like Jupiter," Cushing told Space.com. "So when we study Y dwarfs, we are not only learning about stars, but also about the conditions of gas giant exoplanets.

"Brown dwarfs are also much easier to observe because, in general, they aren't lost in the glare of an exceedingly bright parent star like the majority of exoplanets are."

"Our ultimate goal is to determine what is the least massive brown dwarf that nature can form and how many of these cold brown dwarfs exist near the sun," Cushing added. "This information will help us understand how low-mass stars and brown dwarfs form in general. So we will be continuing to search the sky using WISE for even colder Y dwarfs. We also want to start studying the known Y dwarfs in more detail to determine more-precise temperature estimates, estimate their masses, determine if any of them are actually binary systems and so on.

"The largest obstacle in studying Y dwarfs is that they are extremely faint, so we require the absolute largest telescopes on Earth and the Hubble Space Telescope — and in some cases these telescopes are probably still not sensitive enough."

The scientists detailed their findings about the Y dwarfs in a paper appearing in the Astrophysical Journal and about the 100 new brown dwarfs in a study appearing in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

Follow Space.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit Space.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook .