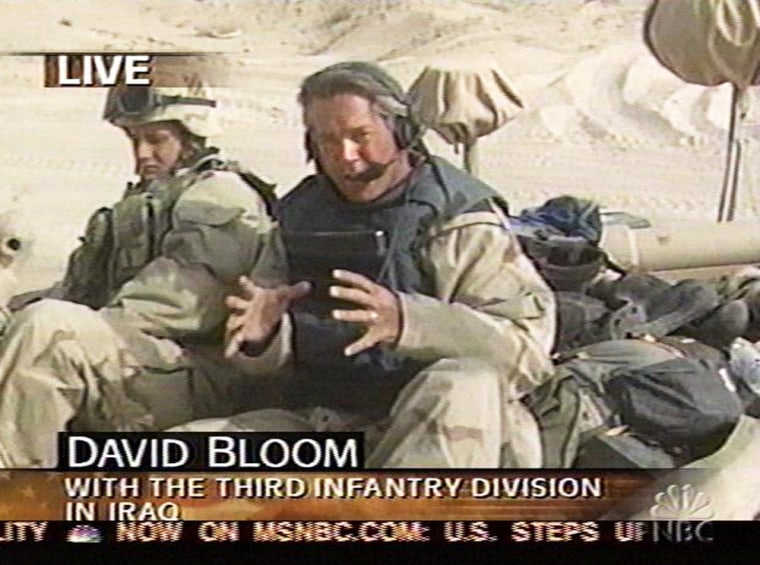

“We’re going along with the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Division. We’re right now in an M88, which is a tank recovery vehicle, which is our means of transportation as we move about on this potential battlefield.”

With those words, and more important, with stunningly clear broadcast-quality pictures of the Iraqi desert rolling behind him, NBC News correspondent and Iraq war military embed David Bloom changed our expectation of war coverage forevermore.

Gone were the taped, day-old reports from some distant battlefield. Bloom was riding atop an armored vehicle and broadcasting the start of the U.S. military’s charge to Baghdad — live. He was up close and very personal. He seemed to be hosting the ultimate reality show — "The Embeds,” where the stakes were literally life and death.

Skeptical

When the Pentagon first floated the idea of “embedding” journalists with military fighting units, I was among the skeptics at NBC News.

From the first Gulf War to the war in Afghanistan, we had been frustrated with the Pentagon’s practice of shutting out the media and controlling the flow of information. However, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to refuse an offer to observe the military first hand.

I was certain the Pentagon would waste our time and money. NBC News would expend a great deal on personnel and equipment to gain only restricted access and grainy video. Military censors would control our correspondents and cameras, and the "government spokesperson" would spin events.

We were wrong.

Instead, for the most part, the Pentagon made good on its promise to allow unfettered, sometimes unflattering coverage of fighting military units.

This would not be the first time reporters were on the battlefield, but it would be the first time we could see and talk with them, live.

Insight

The embeds were given exceptional views of the realities of military life and combat, and they used new technologies to deliver unprecedented coverage of those experiences in real time.

We, along with our viewers, were fascinated as the embeds gave us insight into the lives of the men and women who had volunteered to fight this war.

We learned about MREs (meals-ready-to-eat), digging holes in the sand to sleep in, life in the cramped, closed quarters of a tank, what it is like to wear a chemical suit while fighting in the blistering heat of the desert, and the importance of military underwear.

Fascination turned to fear as we became riveted to our televisions when the embedded reporters broadcast the gunfire, the explosions, and the screams.

We experienced the chaos of a gun battle. We sensed the horrible anticipation of the unknown incoming round and felt the rush of adrenaline and alarm as we were told — through the filter of a gas mask — that the warning sirens had sounded. We shared the tragic loss of soldiers, civilians, colleagues and friends.

Conditions of access

NBC News, and every other news organization that wanted to be embedded with the military, had to agree to some conditions to ensure that our broadcasting would not endanger the lives of military personnel or compromise military operations.

We agreed that we would not broadcast the location and size of military units or identify the wounded and dead before the military could notify their next of kin.

We did not have a problem adhering to those restrictions as they were in line with the self-imposed guidelines that we have followed for years.

To our surprise, we discovered that individual field commanders were given broad authority over access and broadcasting. For the most part, they supported airing news as it happened.

When the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, came under friendly fire near Nasiriyah, 31 soldiers were injured, two critically. NBC News embed Kerry Sanders, who was about three miles away at the time of the shooting, was brought to the scene by the military and allowed to tape the bloody aftermath.

After Sanders’ piece aired, the Marines told him they received a disturbing call from their superiors at Camp Lejeune, their home base. The Marines were outraged that they were reprimanded for allowing an “embarrassing” story to air instead of being asked about the condition of the casualties and the cause of the accident.

Contrary to the thinking at Camp Lejeune, the Marines on the scene wanted their story to be told in the hope that, by raising awareness in the field, they might prevent other soldiers from making the same mistake.

At no time did the commander in the field limit Sanders’ access or ability to broadcast, beyond the agreed-upon restrictions.

Fear of jingoism

We were very concerned from the beginning that no matter how much access the embeds were given, their unique vantage point (just one step behind a U.S. soldier) would provide only narrow, one-sided reports from the battlefield.

To enable us to tell all sides of the story, we assigned unilateral reporting in northern Iraq, Jordan and Kuwait. We put reporters in Ankara, Cairo, Doha, London, Moscow, Washington, Paris, Berlin, Jerusalem, the United Nations and Baghdad. Our military experts added context, and our anchors added perspective.

The embeds’ role was similar to that of a close-up in one of our spots. Their reporting did not tell the entire story, but it helped define our overall coverage by adding detail and intimacy.

We also anticipated the embedded reporters would inevitably share traumatic experiences with the soldiers and become reliant upon them for their personal safety.

We feared jingoism might creep into the reporting and objectivity might become a battlefield casualty.

To counter those threats, we assigned dedicated journalists who understood their mission and boundaries.

Our editorial producers and anchors constantly patrolled our broadcasts and scripts for phrases such as “we attacked,” and “enemy soldiers,” which they revised to “the U.S. military attacked” and “Iraqi soldiers.”

New technology

We are connected via 24-hour cable news, the Internet, e-mail, instant messaging, satellite TV, picture cell-phones and Wi-Fi hot spots. If it happens anywhere in the world, our viewers expect to see it, immediately. Including war. To meet that demand, NBC News would have to develop the new technologies needed to broadcast from the most hostile of environments.

Led by Stacy Brady, NBC’s vice president of network news field and satellite operations, NBC engineers partnered with the Raytheon Corp. and designed a revolutionary, compact portable satellite uplink 1/20th the size and weight of existing models.

In addition to broadcasting our television signal, this uplink had the capability to provide telephone communications and immediate access to the Internet. Standing in the desert, our reporters, producers and engineers were as connected to NBC as they would have been in their offices at 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

However, NBC News embed David Bloom and cameraman Craig White asked for more.

In December 2002, just three months before the start of the war, Bloom called from Kuwait where he had just covered the largest U.S. military live-fire exercise since the first Gulf War.

Bloom, with his trademark enthusiasm, told us he was given permission to embed with the 3rd Infantry Division. The unit would be “at the tip of the spear,” one of the first units into combat, and he and White would be riding with them. Better yet, they would be able to broadcast along the way.

We thought Bloom and White would travel with the troops, stop, set-up, broadcast, break down, and move on. The new Raytheon satellite uplink would work perfectly.

But Bloom, a step ahead of us, impatiently upped the ante. “No, you don’t get it,” he said. They wanted to broadcast live, while riding with the troops into battle.

“Don’t worry,” he added, “we have an idea.”

Their idea was mind-boggling.

Developing the technology

They knew that the big, heavy, clumsy satellite trucks we use on streets in the United States would not survive the off-road terrain of the desert. And a portable satellite dish, even our compact Raytheon, would not fit on top of the tank-recovery vehicle.

They wanted to use a much smaller, and less powerful, microwave dish to send a signal to a microwave receiver on a second vehicle that had the satellite uplink.

That vehicle, which became known as “The Bloommobile” would trail behind at a safe distance of up to five miles. In principle, it should work.

The microwave was capable of linking the vehicles while traveling at speeds approaching 50 mph, but we had never tried uplinking to a satellite from a vehicle that was bouncing and rocking in rough, unpredictable conditions.

In 1998, NBC’s “Dateline” broadcast from the deck of the Titanic recovery ship in the North Atlantic Ocean. It used a gyro-stabilizing satellite dish mount, built by Maritime Telecommunications Network, to overcome the gentle rocking of the ship. Could the mount overcome the severe bouncing in a desert?

In just 40 days, MTN and NBC engineers modified a pickup truck to withstand the hostile terrain of the Iraqi desert and mounted the electronics and satellite dish on the bed.

When they tested it, in secret, on the smooth, paved streets of Orlando, Fla., just four weeks before the start of the war, it didn’t work. The signal dropped out during turns.

The engineers worked frantically to work out the bugs, and NBC’s "secret weapon" was shipped to Kuwait just days before the 3rd ID started the march toward Baghdad.

Accomplishment turned to anguish

When Bloom came up on our screens days later, crystal clear and steady from the middle of the Iraqi desert, we knew NBC News had accomplished something amazing. However, we came to realize later that the true accomplishment was not just the ability to broadcast from the desert. The technological advances had enabled Bloom, and all the embedded reporters, to become a kind of lifeline, the only connection for friends and families to the soldiers who were risking so much to fight this war.

Sadly, as men and women started to fall, that magnificent feeling of accomplishment quickly turned to apprehension and anguish.

NBC News lost Bloom to a pulmonary embolism only 19 daysafter his triumphant broadcast from the desert. We subsequently lost soundman Jeremy Little to a rocket-propelled grenade while on patrol with the 3rd Infantry near Fallujah.

Since the start of the war, more than 550 U.S. soldiers, thousands of Iraqi soldiers and civilians, and 14 journalists have died.

Close to the story

As reporters, we work to keep a safe, detached distance from the story. This facilitates our impartiality and insulates us from the emotions.

For our viewers, the TV screen adds that distance and safety, making it possible to watch the horrible and the tragic. Somehow, our new technology, the embedded reporters, and the stories they told, drew us all closer than we had ever been before. Too close, perhaps.

NBC’s Tom Brokaw and Nancy Chamberlain expressed it best at the start of the war in an interview after the loss of Chamberlain’s son, Marine Capt. Jay Aubin.

Chamberlain: “...I truly admire what all of the network news and all the new technologies are doing today to bring it into our homes. But for the mothers and the wives who are out there watching, it is murder. It — it's heartbreak. We can't leave the television. Every tank, every helicopter: `Is that my son?' And I just need you to be aware that technology is — it's great. But there are moms, there are dads, there are wives out there that are suffering because of this. That's all. That's why I'm doing this.”

Brokaw: “That is so eloquent and it's so appropriate, and we will do whatever we can to reinforce that message repeatedly.”

Chamberlain: “Thank you.”

Brokaw: “We have talked about it here, but probably not enough ... war is not about technology; it is about life and death, young men and young women putting their lives on the line in the service of their country.”

Chamberlain: “That's right.”

Brokaw: “And behind every one of those dots that we show on the screen or behind one of those computer-generated graphics, there is a life that is at risk.”