One of the foundations supporting NASA's case for water's past presence on Mars, at least near the rover Opportunity, is salty chemical forms of sulfur known as sulfates.

These mineral salts were found in abundance during Opportunity's studies of a rock outcrop sitting in its Meridiani Planum landing site.

"With this quantity of sulfates, you kind of have to have a lot of water involved," explained Steven Squyres, principal investigator of Opportunity's science package and a professor at Cornell University.

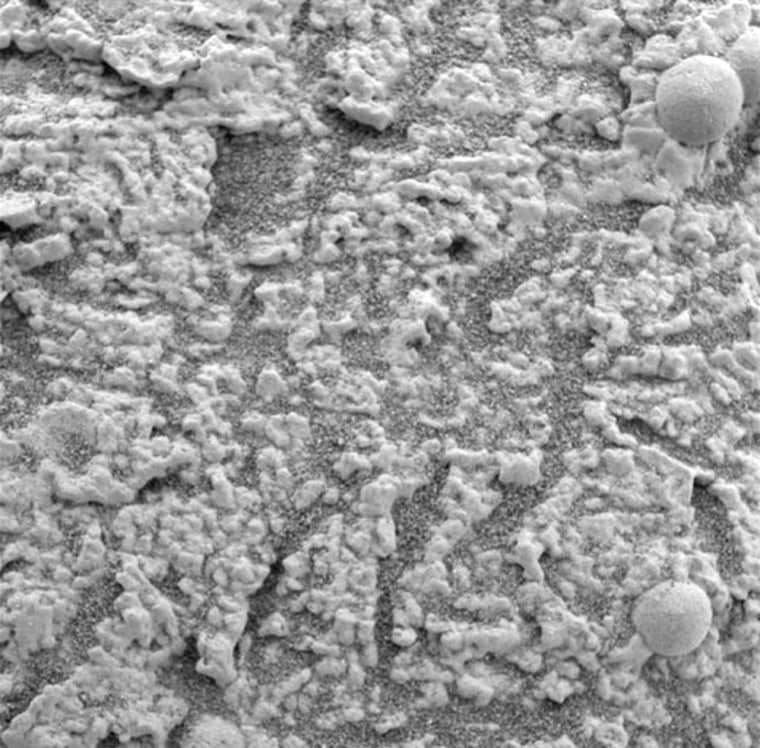

The sulfates were detected with Opportunity's alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, which identifies the chemical elements of a sample. The instrument detected high amounts of sulfur in the nearby outcrop during three weeks of intense study. Among the chemical forms of sulfur present were magnesium, iron and other sulfate salts.

Chief among the sulfates found is jarosite, a hydrated iron sulfate detected by Opportunity's Mössbauer spectrometer, a device that scans for iron-bearing minerals.

"On Earth, the only place we see this mineral is in areas where there is liquid water," said Cathy Weitz, a program scientist with the Mars Exploration Rovers program and Europe's Mars Express mission. Jarosite is typically found in acidic lakes or hot springs, she added.

Opportunity's rock outcrop could also have once sat in an acidic lake or a hot springs environment, NASA officials said.

The detection of magnesium sulfate kieserite, which is similar to epsom salt, and bromide salts were also telltale signs that water existed on the Red Planet. Both are evaporite minerals, and found on Earth in regions where seas evaporate over time.

Benton Clark III, a Mars Exploration Rover team member, said Opportunity's observations showed that the levels of bromide salts increased towards the bottom of the outcrop, but the sulfur levels increased towards the top.

"This is a classic signature of an evaporite," he told Space.com. "Here, water is evaporating, and the salt comes out in these deposits."

Opportunity's handlers can't say for certain that Meridiani Planum was up to its armpits in a salty sea in eons past. It's just as possible that groundwater percolated through the rocky outcrop on the way into the ground. Rover scientists are busy planning further studies over a broader area may help determine what depth, on the surface or otherwise, Martian water may have reached.