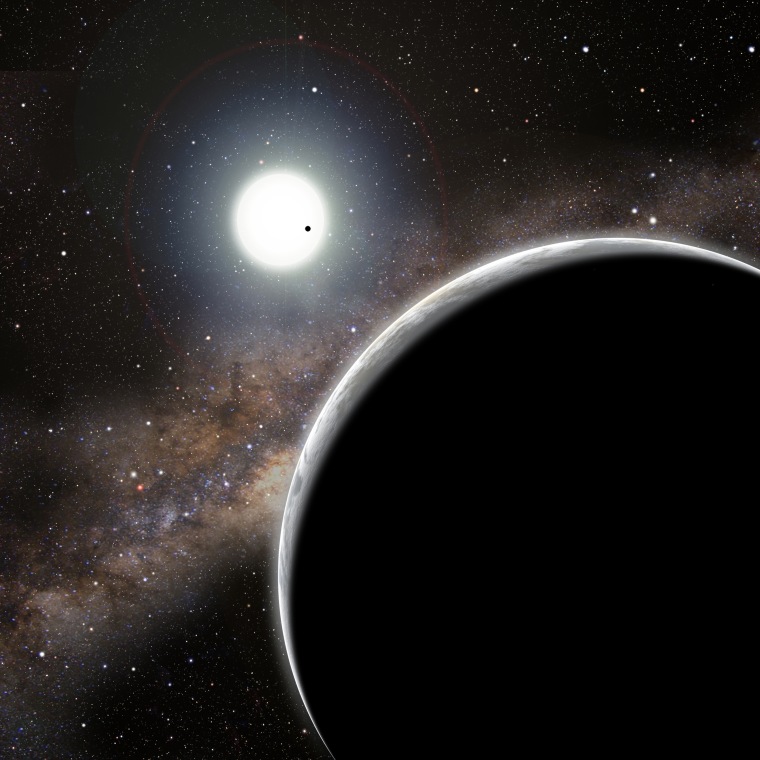

For the first time, scientists have definitively discovered an "invisible" alien planet by noticing how its gravity affects the orbit of a neighboring world, a new study reports.

NASA's Kepler space telescope detected both alien planets, which are known as Kepler-19b and Kepler-19c. Kepler spotted 19b as it passed in front of, or transited, its host star. Researchers then inferred the existence of 19c after observing that 19b's transits periodically came a little later or earlier than expected. The gravity of 19c tugs on 19b, changing its orbit.

The discovery of Kepler-19c marks the first time this method — known as transit timing variation, or TTV — has robustly found an exoplanet, researchers said. But it almost certainly won't be the last. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

"My expectation is that this method will be applied dozens of times, if not more, for other candidates in the Kepler mission," said study lead author Sarah Ballard of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

Finding two new planets

The Kepler spacecraft launched in March 2009. It typically hunts for alien worlds by measuring the telltale dips in a star's brightness caused when a planet crosses the star's face from the telescope's perspective, blocking some of its light.

Kepler has been incredibly successful using this so-called transit method, spotting 1,235 candidate alien planets in its first four months of operation. That's the way it detected Kepler-19b, a world 650 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Lyra.

Kepler-19b has a diameter about 2.2 times that of Earth, researchers said, and orbits 8.4 million miles (13.5 million kilometers) from its parent star. The planet likely has a surface temperature around 900 degrees Fahrenheit (482 degrees Celsius).

Kepler-19b transits its host star once every nine days and seven hours. But that number isn't constant, Ballard and her team found; transits can occur up to five minutes early or five minutes late. That variation told them another planet was tugging on 19b, alternately speeding it up and slowing it down. [Infographic: How Alien Solar Systems Stack Up]

In our own solar system, scientists used similar methods to predict the existence of the planet Neptune. Astronomers noticed that Uranus did not orbit the sun exactly as expected, and surmised that an unseen planet was pulling on it. This prediction was borne out when telescopes confirmed Neptune's existence in 1846.

Researchers know little about Kepler-19c at the moment. It takes the alien world 160 days or less to zip around its host star, and 19c's mass could range from a few times that of Earth to six times that of Jupiter, researchers said.

But 19c should start coming into clearer focus soon.

"It's a mystery world, but of course we don't expect it to remain a mystery," study co-author David Charbonneau, also of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Space.com in an email. "Kepler, and large ground-based telescopes, should help us figure out its true identity soon enough!"

The study will be published in The Astrophysical Journal.

A first for a new method

The new study isn't the first to report evidence of a new alien planet using the TTV method. Last year, for example, a different research team announced the possible discovery of a planet called WASP-3c using the technique.

But WASP-3c is still somewhat ambiguous, researchers said.

"The authors consider that result tentative ... and are collecting more data to confirm that there are timing variations," study co-author Daniel Fabrycky of the University of California at Santa Cruz told Space.com in an email. "The detection is much more certain in our case, as the data come from a single instrument and nearly every transit has been detected over a few cycles of the signal."

Ballard voiced similar sentiments, saying other potential TTV exoplanet finds — such as another possible world in the WASP-10 star system — aren't quite definitive.

"We are just claiming that the Kepler-19 system is the first robust discovery," Ballard told Space.com. "The detection we have is a better-sampled one, and it's also higher signal to noise."

Further, she added, in all other potential TTV finds, the "perturbed" alien planet has been a gas giant orbiting extremely close to its parent star — a so-called "hot Jupiter." But the Kepler mission has shown that hot Jupiters tend to be singletons, circling their stars alone.

"It puts doubt in my mind about the likelihood of an additional perturbing planet in a hot Jupiter system," Ballard said. "I'm not saying it's impossible, but it makes it a little more unlikely."

That's in contrast to Kepler-19b, which is a so-called "super-Earth" just 2.2 times wider than our own planet.

Hunting for alien Earths

Kepler's first TTV exoplanet discovery is in the books, but many more could be coming. Charbonneau estimated that Kepler might eventually discover hundreds of planets using the technique.

Many of these finds would probably not be possible using the traditional transit method, which requires a precise alignment of star, planet and spacecraft to work, he added.

The TTV technique is also sensitive enough to find smaller planets — those that are closer to Earth-size, some of which may even be Earthlike.

"That is the promise of transit timing variations," Ballard said. "I do believe it could discover Earth-mass planets, to say the least. Whether they're Earthlike, I don't know. That would require a lot more study."

You can follow Space.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: . Follow Space.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter and on .