A decades-old battle over school desegregation in Little Rock reached a federal appeals court Monday, as attorneys for schools involved in the case argued that a judge was wrong to cut off tens of millions of dollars in state funding for programs to achieve racial balance.

The 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis heard arguments from the Little Rock, North Little Rock and Pulaski County Special school districts as well as the state of Arkansas, which argues that it shouldn't have to make the payments any longer.

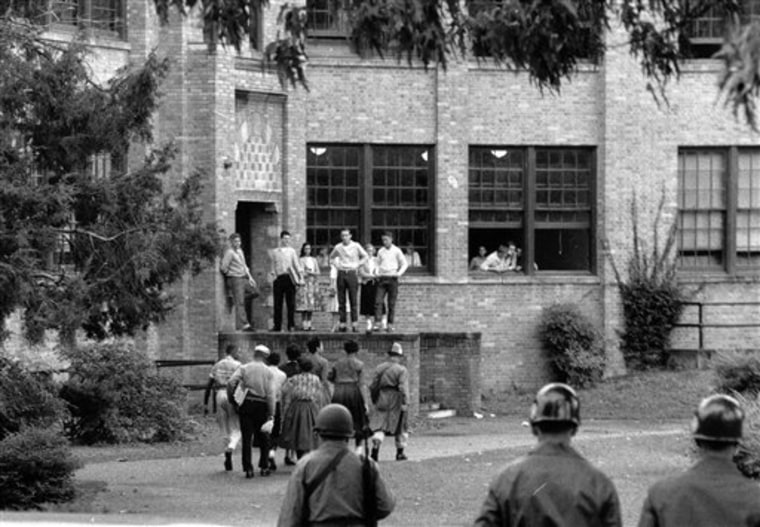

The fight to integrate Little Rock's schools dates back to 1957, when nine black teenagers needed the protection of federal troops to enter all-white Central High School. The state agreed to support busing students between districts and several magnet schools in the city in 1989, and the state is still spending about $70 million a year for desegregation efforts under that settlement with the three districts.

Chris Heller, the longtime attorney for the Little Rock School District, told the appeals court Monday that a lower court judge overstepped his authority when ruled in May to cut off most of those payments. He cited a 2000 case involving Kansas City's schools in which he said the appeals court used similar reasoning.

"You really can look no further than this court's own opinion," Heller said. "The cases are almost identical."

Stephen Jones, attorney for the North Little Rock schools, accused the same judge of not being clear in his order.

"It's difficult for us to respond to his criticisms when he doesn't tell us what they are," he said.

But Assistant Attorney General Scott Richardson argued that the districts have had enough time and enough money — more than $1 billion in state payments since a 1989 settlement — to desegregate.

Eventually, the payments would have to end, and "that's something that's been discussed for years," Richardson said.

The schools now serve about 50,000 students and have come a long way since the governor and hundreds of protesters famously tried to stop the Little Rock Nine. But thousands of white and black children still are bused to different neighborhoods every day under one of the nation's largest remaining court-ordered desegregation systems.

State lawmakers want to end the payments, saying the payments are wasteful, but the school districts argue that the money is still needed to fund programs such as magnet schools and voluntary busing.

Some parents have reacted to the uncertainty about future payments by looking to enroll their children in charter or private schools.

In his May 19 ruling to end the payments, U.S. District Judge Brian Miller accused the districts of delaying desegregation to continue getting state money.

Miller, describing himself as a "middle-aged black judge," concluded that "few, if any, of the participants in this case have any clue how to effectively educate underprivileged black children."

___

Associated Press writer Nomaan Merchant reported from Little Rock.