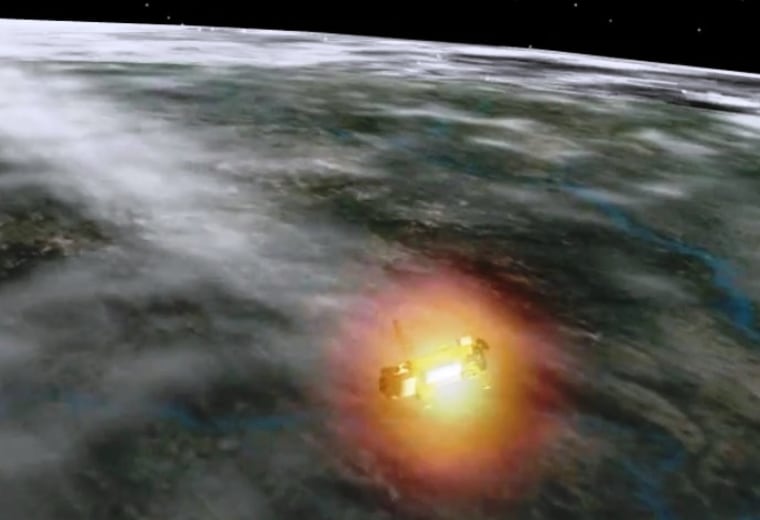

After days of worldwide suspense, NASA declared Saturday that its six-ton Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite came apart during a fiery fall over the Pacific Ocean.

The space agency said the decommissioned spacecraft fell back to Earth between 11:23 p.m. ET Friday and 1:09 a.m. ET Saturday. NASA spokesman Bob Jacobs said the Joint Space Operations Center, headquartered at California's Vandenberg Air Force Base, reported that the satellite entered the atmosphere over the Pacific.

"Precise time and locale aren't yet known," he added in a Twitter update.

Hours after the satellite's demise, it was still occasionally hard to separate the truth from the fakery. There were multiple reports of fireballs and bright debris being sighted over Canada, but one of those reports turned out to be a "War of the Worlds" prank — which led Jacobs to complain on Twitter about "a lot of hoax data and false info going viral."

Determining the precise time and place of impact was difficult because of the uncertainties surrounding the satellite's altitude toward the end.

Any surviving wreckage was expected to be sparsely distributed across a 500-mile-long (800-kilometer-long) ellipse. "The risk to public safety was very remote," NASA said in a statement.

Delayed demise

The projected time of re-entry was pushed later and later during the satellite's final hours. "It just doesn't want to come down," said Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

McDowell said the satellite's delayed demise demonstrates how unreliable predictions can be.

Until Friday, increased solar activity was causing the atmosphere to expand and the 35-foot, bus-size satellite to free fall more quickly. But late Friday morning, NASA said the sun was no longer the major factor in the rate of descent and that the satellite's position, shape or both had changed by the time it slipped down to a 100-mile (160-kilometer) orbit.

"In the last 24 hours, something has happened to the spacecraft," said NASA orbital debris scientist Mark Matney.

Uncontrolled re-entry

The Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite, or UARS, was the biggest NASA spacecraft to crash back to Earth, uncontrolled, since the post-Apollo 75-ton Skylab space station and the more than 10-ton Pegasus 2 satellite, both in 1979.

Russia's 135-ton Mir space station slammed through the atmosphere in 2001, but that was a controlled dive into the Pacific.

NASA expected about two dozen pieces of the UARS satellite — representing 1,200 pounds of heavy metal — to survive re-entry. The biggest surviving chunk should have been around 300 pounds (150 kilograms).

Earthlings can take comfort in the fact that no one has ever been hurt by falling space junk — to anyone's knowledge — and there has been no serious property damage. NASA put the chances that somebody somewhere on Earth would get hurt at 1-in-3,200. But any one person's odds of being struck were estimated at 1-in-22 trillion, given that there are 7 billion people on the planet.

"Keep in mind that we have bits of debris re-entering the atmosphere every single day," Matney said in brief remarks broadcast on NASA TV.

In any case, finders definitely aren't keepers.

Any surviving wreckage belongs to NASA. If someone finds a piece of it, NASA has the right to ask for its return. There are no toxic chemicals on board, but sharp edges could be dangerous, so the space agency warned the public to keep hands off and call the authorities.

Minimizing space junk

The $740 million UARS was launched in 1991 from the space shuttle Discovery to study the atmosphere and the ozone layer. At the time, the rules weren't as firm for safe satellite disposal; now a spacecraft must be built to burn up upon re-entry or have a motor to propel it into a much higher, long-term orbit.

NASA shut UARS down in 2005 after lowering its orbit to hurry its end. A potential satellite-retrieval mission was ruled out following the 2003 shuttle Columbia disaster, and NASA did not want the satellite hanging around orbit posing a debris hazard.

Space junk is a growing problem in low-Earth orbit. More than 20,000 pieces of debris, at least 4 inches in diameter, are being tracked on a daily basis. These objects pose a serious threat to the International Space Station.

This report includes information from The Associated Press and msnbc.com.