Scientists may be able to spot evidence of elusive dark matter by watching for ripples on the surfaces of stars, a new study suggests.

Such vibrations could indicate that a strange, hypothetical dark-matter object known as a primordial black hole has passed through the stars, according to the study. The ripples could thus provide observable proof of dark matter, which is thought to make up more than 80 percent of all matter in the universe but has thus far evaded direct detection.

"There's a larger question of what constitutes dark matter, and if a primordial black hole were found it would fit all the parameters," study co-author Shravan Hanasoge of Princeton University said in a statement. "Identifying one would have profound implications for our understanding of the early universe and dark matter."

The hunt for dark matter

Scientists believe that only 4 percent of the universe is made up of "normal" material that we can see. The rest is strange stuff called dark energy and dark matter.

Though dark matter is thought to dominate the universe, scientists still have not observed the stuff directly, instead inferring its existence through gravitational effects on the matter they can see.

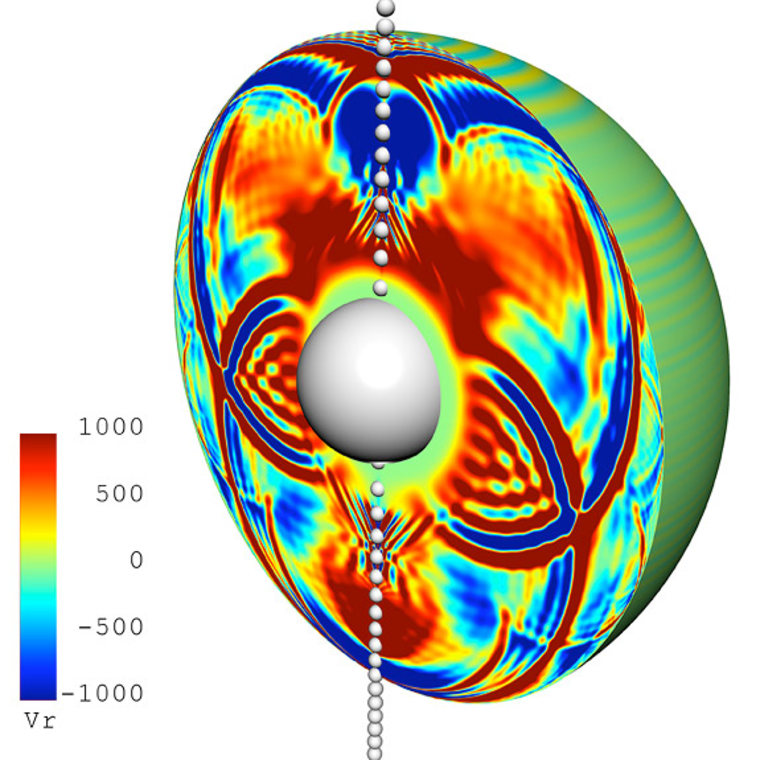

The new study could help scientists get a better handle on what dark matter is, researchers said. They simulated what would happen if a primordial black hole passes through a star.

Primordial black holes are theoretical remnants of the Big Bang, the explosive event that created the universe. These odd objects, which have yet to be observed, are one of various cosmic structures that may be the source of dark matter, researchers said.

Primordial black holes are much smaller than "normal" black holes and thus would not swallow up a star and all of its light. Rather, their collisions with stars would cause noticeable vibrations on the stars' surfaces.

"If you imagine poking a water balloon and watching the water ripple inside, that's similar to how a star's surface appears," said lead author Michael Kesden of New York University. "By looking at how a star's surface moves, you can figure out what's going on inside. If a black hole goes through, you can see the surface vibrate."

Just a matter of time?

The researchers' simulations also put some numbers on just how large a primordial black hole would have to be to cause a noticeable ripple. They found that an object about the mass of a decent-size asteroid would do the trick.

If primordial black holes are for real, scientists should be able to spot one at some point, researchers said.

"Now that we know primordial black holes can produce detectable vibrations in stars, we could try to look at a larger sample of stars than just our own sun," Kesden said. "The Milky Way has 100 billion stars, so about 10,000 detectable events should be happening every year in our galaxy if we just knew where to look."

The researchers published their results this month in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Follow Space.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter and on .