For weeks to come, NASA will be working with the aerospace industry on its plans to develop its new super-sized rocket for missions back to the moon, the nearest Lagrangian point, asteroids, Mars and other ports of call in deep space.

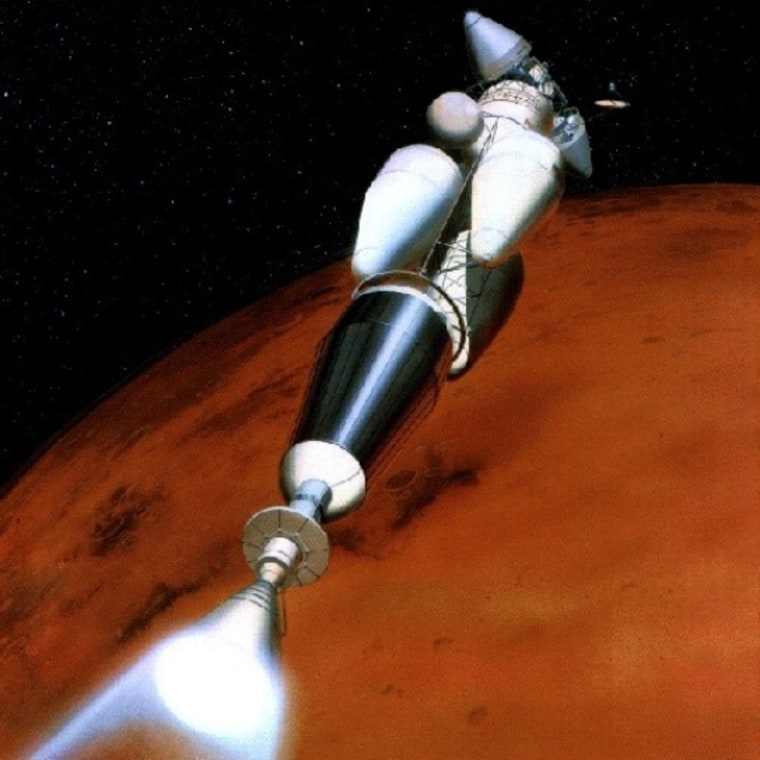

The agency will be working with the latest technology, as well as innovations yet to be invented. Some even dare to whisper rocketry's N-word: nuclear.

But first, it seems logical to assume that NASA will use what it has.

For the initial flight tests, NASA’s new heavy-lift rocket will use two five-segment versions of the space shuttle’s solid-rockets. The solids will be strapped to a tank structure equipped with shuttle-style main engines, forming the basic “core stage.”

The second stage will use the J-2X engine, an updated version of the upper-stage rocket that powered the Saturn 1B and Saturn V rockets in the 1960s and '70s. The system was used for 16 manned space missions, including nine Apollo flights that carried crews to the moon and back.

When the last Apollo moon ship made its final voyage in 1972, few people would have guessed that the gap in deep-space exploration would last so long. Here's how the scene played out, as described in "Moon Shot," the book I wrote with NASA chief astronaut Deke Slayton and Alan Shepard, America's first astronaut and one of only 12 men who walked on the lunar landscape:

The end of the space race: An excerpt from 'Moon Shot'

The last man on the moon, Gene Cernan, paused for a final look at the black beauty of the world about him. He had a message to send home before departing. "As I take these last steps from the surface for some time in the future to come, I’d just like a record that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And as we leave the moon and Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and, God willing, we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind."

It will be 39 years this December since he spoke those words. No American, no earthly being has yet returned to the moon. Sadly, no one will again for some time to come.

Within a period of four years, 24 American astronauts, some twice, sailed through the vacuum from Earth to the moon. Twelve out of those 24 rode their landers down to the lunar surface, walked and drove through the dust and rocks of the small world.

Had the Soviet Union sustained its early lead in power and technology over the United States, the number of humans going might have increased greatly. It was a fierce competition, and the Soviets went all-out in their desperate attempts to lead the human race to another solar body, small though it might be and devoid of life. The Russians went through a series of devastating rocket explosions and suffered equal costly failures after reaching earth orbit.

Just two weeks before the last Apollo departed for the moon, the Russians were down to a last-gasp hope that their mammoth N-1 rocket, even more powerful than Wernher von Braun’s spectacularly successful Saturn V, would enable them, at least, to reach the moon during the same period.

It was not to be. The fourth launch of the N-1, intended to fire a large and heavy unmanned lunar lander directly to the moon in a rehearsal for a manned flight, was ripped apart by a series of violent explosions as it climbed through the atmosphere. When the wreckage tumbled back to earth, it sounded the death knell of the Russian manned lunar effort.

Bitter and frustrated, the Soviet government insisted it had never been in the moon race. History records otherwise. Several Russian manned landers became dust collectors in remote hangars. The rocket stages and enormous fuel tanks of the leftover N-1s were hammered into storage sheds and playgrounds for children.

Reinventing the rocket

Thirty-six years after Gene Cernan left the moon, the Obama administration swept into office and brought with it those who insisted on reinventing the wheel. They kicked everything that did work, as well as the things that didn’t, out the door — leaving them with paper drawings. For nearly three years this resulted in massive confusion, infighting and tortuous delays between those from blue and red states.

The ones who plucked sanity from this ungodly mess proved to be the ones who had been sanely chosen to head America’s space agency.

Charles Bolden, an African-American born in South Carolina, shook off the shackles of segregation in a Jim Crow south, and with the help of a congressman from Detroit entered the U.S. Naval Academy, walking in the footsteps of astronauts Alan Shepard and Tom Stafford. Bolden became a major general in the Marine Corps after proving his mettle as a test pilot and space shuttle commander. He became NASA's administrator in 2009.

Bolden laced up his combat boots and stomped his way into the middle of the disorder with his second-in-command, Deputy Administrator Lori Garver, who first dipped her toe in Space Lake as an intern for John Glenn's presidential campaign in 1984.

Bolden quieted the fight over NASA's future and reached into his bag of “things that work.” Satisfying the majority, he and Associate Administrator William Gerstenmaier came up with a heavy-lift deep-space rocket derived from Apollo, the space shuttle and the canceled Constellation back-to-the-moon program.

NASA's plan calls for using proven rockets and facilities — and most importantly, the space agency's experienced workers — to build a new system for deep-space exploration. The Space Launch System, or SLS, is projected to cost taxpayers $3 billion a year, about $1 billion a year less than the space shuttle, through 2017 when the first test flight is scheduled to take place.

There’s little doubt that NASA can build a heavy-lift rocket to fly astronauts beyond Earth orbit, but can the agency build one that can reach deep-space ports without going nuclear?

Nuclear perspective

"Nuclear propulsion should be included when considering deep-space travel," said Princeton physicist Gene H. McCall, retired chief scientist for the Air Force Space Command and a senior scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory. "The engines could also be used for years as a power source for establishing a base on the moon or Mars, or any long-term base where gathering power from the sun would be difficult.”

McCall said the arguments over nuclear space propulsion "are usually emotional rather than technical.”

While I was growing up on the family farm, my father tried for years to bring electricity to our rural area of Georgia, only to be met with protests motivated by fear of electrocution and fires. Irrational fear of the unknown has been with us since the dawn of humanity. But consider this: You can count the deaths in this country from nuclear energy on one hand. Meanwhile, 40,000 Americans die every year on our highways, yet practically no one hesitates to ride in an automobile.

Just ask someone what was the worst nuclear accident in America’s history. Most will tell you it was Three Mile Island in 1979. But when you follow up by asking, "How many died?" ... you are met with a wide stare.

Little is really known by the public about nuclear energy, let alone nuclear propulsion. McCall was involved in closing the Rover and Nerva experimental programs at Los Alamos, and in transferring people and equipment to appropriate places in the nascent laser program, which had strong nuclear connections. In the process, he became very familiar with the nuclear rocket program and its prospects.

"Nuclear fuel has a very high energy density," McCall said. "One can design a nuclear rocket with one-half the mass of a liquid or a solid [rocket] and double its payload while cutting travel time by half."

The nuclear rocket operates by heating liquid hydrogen and pushing it out a nozzle at the rear of the reactor. The low molecular weight exhaust and high velocity give a high specific impulse. The power is precisely controllable.

"Specific impulse is the most important quality of a rocket’s fuel," McCall explained. "It tells you how fast you can go and how efficient your rocket fuel is. You might call it 'fuel quality.'"

Toward the end of their tests, McCall and the rest of his team built a reactor capable of rocket flight. "Called Nerva, it ran more than two hours, with 20 minutes of the time being at full power," he said. "At full power, it generated 75,000 pounds of thrust into a vacuum, and demonstrated a specific impulse of 850 seconds, more than any of our liquid or solid rockets yet flown.

“Thus, based on experimental evidence, nuclear rockets have a specific impulse, and a payload capability, twice that of a liquid or a solid.”

McCall mused on the past and the future of nuclear propulsion. "In a logical world, unfortunately not the one we live in, the choices of propulsion systems for deep-space travel, the moon and beyond, would be first nuclear by large margin," he said.

America has already accepted nuclear propulsion for ships and submarines. If the children and grandchildren of today’s space family are to navigate what John F. Kennedy called "this new ocean," to reach Mars and other deep-space ports, irrational fears must give way to logic — just as they did when Columbus sailed, when the wagon trains left Saint Joe, and when Orville and Wilbur dared to fly.

If humankind is to survive, knowledge must always triumph over anxiety.

More excerpts from 'Moon Shot':

NBC News' Jay Barbree is the only journalist to cover every spaceflight flown by astronauts from Cape Canaveral. He has won NASA’s highest medal for public service and the National Space Club’s 2009 Press Award. Barbree also has written several books about the space effort, including an updated version of published by Open Road Integrated Media and available from , , , and . "Moon Shot" excerpt updated and reprinted with permission, copyright 2011.