Stepping into a battle between the liberal and conservative justices on the U.S. Supreme Court, Republican House members are protesting the court’s increasing use of foreign legal precedents in interpreting the Constitution.

Republican House members Tom Feeney of Florida and Bob Goodlatte of Virginia, joined by more than 50 co-sponsors, will propose a non-binding resolution next week that would express the sense of Congress that judicial decisions should not be based on foreign laws or court decisions.

While Feeney and Goodlatte, who are members of the House Judiciary Committee, can’t summon the justices before them to defend their use of foreign precedents, they hope to fire a rhetorical shot across the bow of jurists who increasingly look to foreign legal trends, especially in death penalty and gay rights cases.

Feeney even used the “I” word, impeachment, in an interview with MSNBC.com in his House office Wednesday.

“This resolution advises the courts that it is improper for them to substitute foreign law for American law or the American Constitution,” Feeney said. “To the extent they deliberately ignore Congress’ admonishment, they are no longer engaging in ‘good behavior’ in the meaning of the Constitution and they may subject themselves to the ultimate remedy, which would be impeachment.”

He added, “I don’t think there’s any interest in the majority members of Congress in impeaching justices, but there is a huge interest in the Constitution as the supreme law of the land and we want the justices to recognize that and to follow it”

Since 1977 and especially in the last five years, Justices John Paul Stevens, Stephen Breyer, and Anthony Kennedy have cited foreign decisions to buttress their views:

- In a 1999 death penalty case, Breyer, citing judicial decisions from Jamaica, India, Zimbabwe, and the European Court of Human Rights said, “A growing number of courts outside the United States … have held that lengthy delay in administering a lawful death penalty renders ultimate execution inhuman, degrading, or unusually cruel.”

- In a 2002 case that ruled that mentally retarded people convicted of murder could not be given a death sentence, Stevens contended that “within the world community, the imposition of the death penalty for crimes committed by mentally retarded offenders is overwhelmingly disapproved,” citing a legal brief from the European Union as his authority.

- Last year in the landmark Lawrence v. Texas decision that struck down the state’s sodomy statute, Kennedy, writing the majority opinion, referred approvingly to the British Parliament decriminalizing sodomy in 1967, the European Convention on Human Rights, and a 1981 European Court of Human Rights case.

Referring to the two men seeking to have the Texas law declared unconstitutional, Kennedy wrote, “The right the petitioners seek in this case has been accepted as an integral part of human freedom in many other countries.”

For his critics, Kennedy’s argument seemed to amount to: If it’s good enough for Europe, it ought to be good enough for the United States.

Deep divide

Kennedy’s opinion underscored the divide between liberals and conservatives on two of the most contentious issues in American society, sexual mores and capital punishment. Liberals see the United States as lagging behind Europe in its views. Conservatives are quite happy that America marches to the beat of its own drummer on these issues.

Last October, in a speech in Atlanta, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor added fuel to the controversy over foreign precedents, predicting that “over time we will rely increasingly, or take notice at least increasingly, of international and foreign courts in examining domestic issues.”

"The impressions we create in this world are important and they can leave their mark," O'Connor said in remarks quoted in the Atlanta Constitution. Looking to foreign precedents "may not only enrich our own country's decisions, I think it may create that all-important good impression."

In his 1999 reference to decisions from Zimbabwe and other countries, Breyer previewed some of O’Connor’s argument that citing foreign precedent may help cultivate goodwill with other nations.

'Decent respect' for foreign views

Quoting the words of the Declaration of Independence, Breyer said, “Willingness to consider foreign judicial views in comparable cases is not surprising in a Nation that from its birth has given a ‘decent respect to the opinions of mankind.’”

He argued, “This court has long considered as relevant and informative the way in which foreign courts have applied standards roughly comparable to our own constitutional standards in roughly comparable circumstances. In doing so, the Court has found particularly instructive opinions of former (British) Commonwealth nations insofar as those opinions reflect a legal tradition that also underlies our own Eighth Amendment.”

But Feeney sees the Lawrence case and other recent citations of foreign precedent as going far beyond finding something “informative” in how other nations use the British legal tradition.

“The people of the United States have never authorized through their Congress or through a constitutional amendment any federal court to use foreign laws to essentially make new law or establish some rights or deny rights here in the United States,” he said.

The Florida Republican also noted, “If they are going to look to foreign laws, our judges have some 200 different countries they can choose from.” Some scholars agree that the justices’ reliance on foreign precedent opens the way to an arbitrary selection of cases that suit particular justices’ views.

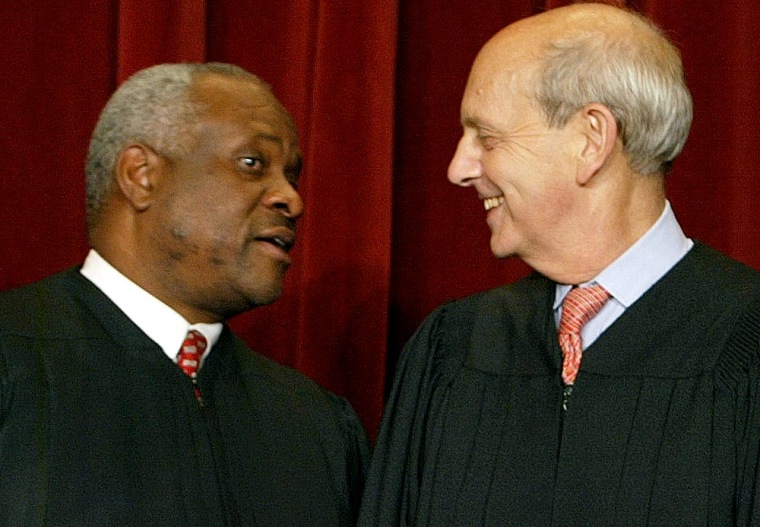

The Feeney-Goodlatte resolution is in tune with Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice William Rehnquist who hold that judges should look only to U.S. and British colonial precedents, such as Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, to interpret the U.S. Constitution.

Thomas opposes 'foreign fads'

"While Congress, as a legislature, may wish to consider the actions of other nations on any issue it likes, this Court’s ... jurisprudence should not impose foreign moods, fads, or fashions on Americans," Thomas said in a 2002 death penalty case.

Dissenting from the majority decision to strike down the Texas sodomy law last year, Scalia said, “the Court’s discussion of these foreign views (ignoring, of course, the many countries that have retained criminal prohibitions on sodomy) is… meaningless dicta,” meaning mere opinion that was not legally binding.

But Scalia called invoking foreign precedent a “dangerous” practice.

In his dissent in Atkins v. Virginia, the 2002 death penalty case in which Stevens invoked the authority of “the world community” Scalia tartly said it was “irrelevant” what other counties thought.

He ridiculed “the practices of the ‘world community,’ whose notions of justice are (thankfully) not always those of our people.”