The fictional Cheshire cat's smile seemed to have a life of its own, outside of the cat's body, and now new research suggests the world's first teeth grew outside of the mouth before later moving into the oral cavity.

The study, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, supports what is known as the "outside-in" hypothesis of tooth evolution. The first teeth and smile, however, did not belong to a cat, but likely were flashed by small and spiny sharklike fish.

That initial smile would have looked rather sinister.

"The first smile would probably have been a prickly one, with many tiny teeth that looked like pointy cheek scales, and other small toothlike scales wrapping around the lips onto the outside of the head," co-author Mark Wilson told Discovery News.

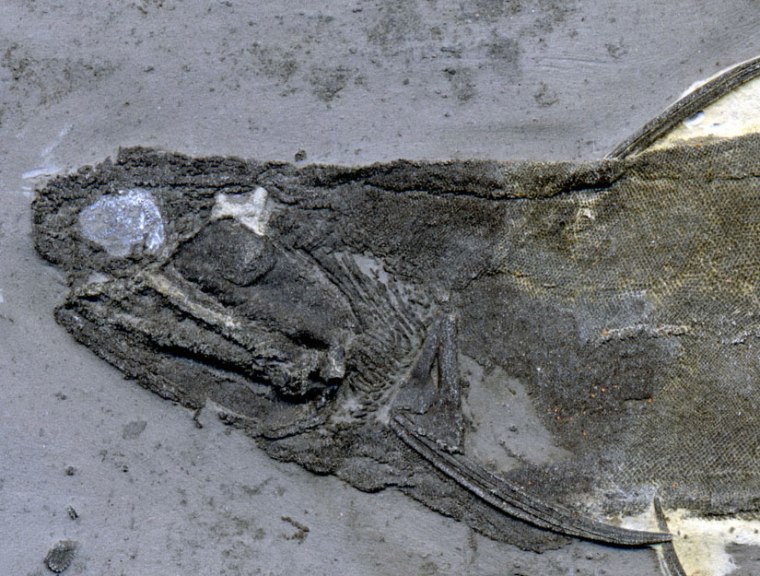

For the study, Wilson, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta, and his colleagues studied animals called ischnacanthid acanthodians, an extinct group of fish that resembled sharks. They lived during the Early Devonian period, which lasted from 416 to 397 million years ago.

The researchers determined that head scales from these fish were in transition, evolving from scales to teeth. The pointy structures were identified on the lips of the fish. This discovery helps to negate the “inside out” theory of tooth evolution, which holds that the first teeth emerged from structures in the pharynx progressing into the mouth.

Project leader Stephanie Blais, a University of Alberta researcher, told Discovery News that "our findings support the idea that teeth evolved from modified pointed scales on the mouth margins (lips) as we see in Obtusacanthus," one of the prehistoric fish included in the study. All of the analyzed fish specimens were excavated at the Man on the Hill site in the Mackenzie Mountains of Canada.

As to why teeth first evolved, Blais said they "would have conferred a major advantage in terms of food acquisition. Pointed scales near the margins of their mouths would have helped them grasp prey and hang on to it until they could swallow it whole."

Such prey consisted of "probably whatever they could swallow," co-author Lindsay MacKenzie of the University of Montana’s Department of Geosciences told Discovery News. Based on fossilized stomach contents and other evidence, their primary prey probably consisted of arthropods, including crustaceans, as well as a variety of soft-bodied creatures and fish.

Blais said jaws, which must have evolved earlier, and the toothlike formations "allowed fishes to change from a filter-feeding or mud-grubbing more passive lifestyle to one of active predation."

The world's first aggressive conflicts also may have arisen at this point, since the move from passive feeding to hunting led to what Blais termed "the very first evolutionary arms race" among vertebrates, with some becoming predators and others becoming prey.

The first teeth also probably first arose in sets, and not just as a single tooth here and there. MacKenzie explained that "scales and teeth exist in developmental fields in which similar developmental processes generate many similar tooth or scale elements." Since the first teeth likely arose from these scales, they then to some extent mirrored the prior scale groupings, emerging as sets of teeth.

There is a connection between human teeth and these first fish teeth.

"Because teeth would have allowed vertebrates to become more efficient predators, and eventually more efficient herbivores, they were retained and passed down through generations in most groups," Blais said.

While humans and other animals with teeth share this initial fish connection, a lot of evolution, as well as inter-species battles, occurred over the millions of years.

"Interactions between predators and prey through time only increased their (teeth's) importance, leading to highly specialized teeth, such as those in mammals," Blais said.