An intensifying space race is taking place in Asia, policy experts say, even if officials from the countries' space agencies are unwilling to acknowledge it.

This increasing competitiveness is fueling regional tensions, and without greater cooperation among Asian space nations, there is a risk for future confrontations and the further militarization of space, said James Clay Moltz, an associate professor in the department of national security affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif.

Moltz penned a commentary about Asia's " unspoken space race " that was published today in the journal Nature.

"I think it's very real," Moltz told Space.com. "I've spoken with officials in multiple countries, and it's very clear that, even if they're not willing to say so, they're watching what their neighbors are doing very carefully, and they're concerned about relative prestige."

While China's burgeoning space program has been at the forefront, other countries such as Japan, India and South Korea have also been steadily expanding their orbital ambitions.

China in space

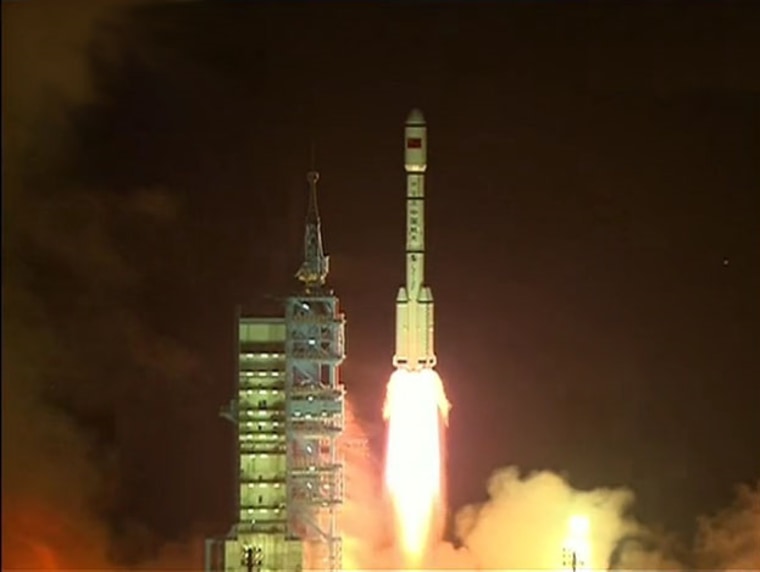

In 2003, China reached a critical milestone when it launched its first manned spacecraft, Shenzhou 5, on a 21.5-hour jaunt in orbit. The achievement made China only the third country, after Russia and the United States, to independently launch a human into space. It was also a wake-up call for other Asian spacefaring nations.

"If we pick 2003 as the beginning of a turning point, the Shenzhou 5 flight really put the other countries on notice," Moltz said. "When you look at what's happening throughout Asia, you see a general growth in interest and activity, and an increased sense of urgency."

China followed up with two more manned missions in 2005 and 2008, and in September of this year, the country launched its first unmanned prototype space lab module to orbit. A visiting robotic spacecraft called Shenzhou 8 subsequently completed two separate docking tests in November, paving the way for China's goal of constructing a manned space station in orbit by 2020.

But the Chinese are not alone. Japan is a member of the International Space Station, and has completed 15 manned missions since 1992, all aboard American and Russian vehicles.

India is also emerging as a competitive space power, launching satellites and space observatories atop the country's own rockets. India also recently announced its goal of launching its own astronauts into space by 2016, Moltz said.

Furthermore, China, Japan and India have all conducted independent robotic moon missions to study and map the lunar surface. Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and Taiwan are also in the midst of expanding their space capabilities, Moltz added.

A more crowded space

Asia's space activity is part of a larger trend, as more and more countries around the world are realizing the benefits of having an active presence in space, said Victoria Samson, Washington Office director of the Secure World Foundation, an organization dedicated to the peaceful use of outer space.

"In the Cold War, we just had a handful of actors, but now there's a broader part of the global population that looks at space as something that is attainable, good for national policy and a way to encourage science and technological development," Samson told Space.com.

But Asian countries have been less willing to work together to achieve their objectives, which is raising concern among policy experts. Unlike the European Space Agency (ESA), which was established in 1975 and consists of 18 member states, Asian space nations have tended to conduct their space activities independently.

"Where there's close cooperation in ESA, there's very little peer-to-peer cooperation in Asia," Moltz said. "Asia really stands out as countries that are pursuing nationalistic policies in space. The major spacefaring nations in Asia simply don't cooperate, and I think that's a real problem. They also don't have a tradition of engaging in regional security dialogues and arms control. If the current Asian space race turns more into a military space competition, I see great instability."

There are two exceptions to this trend: China established the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization in 2008 to coordinate joint space science and research projects with Bangladesh, Iran, Mongolia, Pakistan, Peru and Thailand. And Japan hosts the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum, which consists of annual conferences and training programs for 269 organizations from 33 countries and regions, including some from China.

But, these organizations largely serve the competing interests of the host nations (either China or Japan) and are less geared toward regional cooperation than their names would suggest, Moltz said.

Competitors versus partners

Still, the space competitiveness seen in Asia is certainly not a new paradigm. Beginning in the 1950s and lasting into the early 1970s, the United States and the former Soviet Union were the major players in the definitive space race. These Cold War rivals were fierce competitors as they pushed to be the first to achieve various milestones in space exploration, with the pinnacle achievement being the U.S. manned moon landing in 1969.

In the 1970s, as the space race began to subside, the two countries fostered a mutual environment of cooperation and partnership in space, culminating in their partnership on the assembly of the International Space Station. A similar scenario could play out among Asian space nations as well, Samson said.

"A lot of it may be growing pains," she said. "When we look at it, we have the advantage of over 50 years of experience on space cooperation and space efforts. A lot of these countries are new at it, and it could be a bunch of independent actors now, but 15 or 20 years down the road, maybe things will solidify more into cooperative agreements."

In Asia, the space race is fueled in part by long-standing geopolitical feuds, Moltz said. By pursuing competing national agendas, these countries are not only strengthening regional tensions, they are also fostering scientific duplication rather than sharing costs and pooling resources.

"The past is very much current in Asia, and space is part of the larger fabric of political tension," Moltz said. "It's going to be difficult to solve these problems in isolation without dealing with broader security issues."

The secrecy that shrouds China's space activities, plus the close relationship between the country's civilian and military space programs, has contributed to regional apprehensions, Moltz added, with some concerned that Asia's space race could turn into an arms race.

Militarization of space

In 2007, China destroyed one of its own defunct weather satellites as a test of anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons technology. China was chastised for the demonstration, which created more than 3,000 pieces of orbital debris, but the event also bolstered China's reputation for military prowess in space.

As a response, countries such as India and Japan have increased their military space activities. Samson wrote an article published last month in the journal India Review about the relationship between India, China and the United States and India's increasingly militarized space program.

"India is the one I'm worried about in terms of missile defense capabilities," Samson said. "They have the capacity for anti-satellite weapons. Anything is possible. I think it would have to get to the point where the space program moves away from purely national development and then you might see ASAT weapons, but militarization of the space program would be the first step."

Greater cooperation and dialogue between Asian spacefaring nations could stem this increasing tide of space militarization and promote future partnerships toward shared goals.

The catalyst for such cooperation will likely have to come from China, since it is the dominant player in the field, Samson added. While it's difficult to predict, China's exclusion from the International Space Station could actually be one of the motivating factors for Asian countries to work together in the future, she said.

"Since China is really the 800-pound gorilla, they're going to be the one who has to take the lead," Samson said. "This is purely hypothetical, but it would definitely be interesting if the Chinese space station proved to be that."

You can follow Space.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow Space.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.