In setting up its new program to test U.S. cattle for mad cow disease, the U.S. Department of Agriculture heeded some expert advice.

Specifically, it abided by recommendations from a panel of international researchers, convened in January by Agriculture Secretary Ann Veneman, which suggested testing all high-risk cattle. The panel also sought a “random sample” of healthy cows, in part to discourage farmers from sending sick cattle in for slaughter.

“We’re uniformly supportive of what they’re [the USDA] proposing to do,” said veterinary epidemiologist William Hueston, the panel’s sole U.S. member.

Hueston, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Animal Health and Food Safety, believes the government will collect as many samples as possible out of the total U.S. high-risk population of 446,000 cows. But, he adds, “There’s no way to get every one.”

Hueston believes at least two or three more cases may be found. Those cases, he says, could help researchers hone in on the cattle at highest risk.

On the other hand, he and others dismiss Japan’s universal testing approach. BSE often takes years to incubate in an animal, so researchers point out that tests in cattle younger than 18 months, the disease’s shortest known incubation time, would turn up nothing.

“It would be like testing Alzheimer’s in a 10-year-old,” says Fabio Rupp of Swiss firm Prionics, which developed mad cow tests now used in several nations.

More labs, new tests

Testing a cow for BSE remains a logistical scramble.

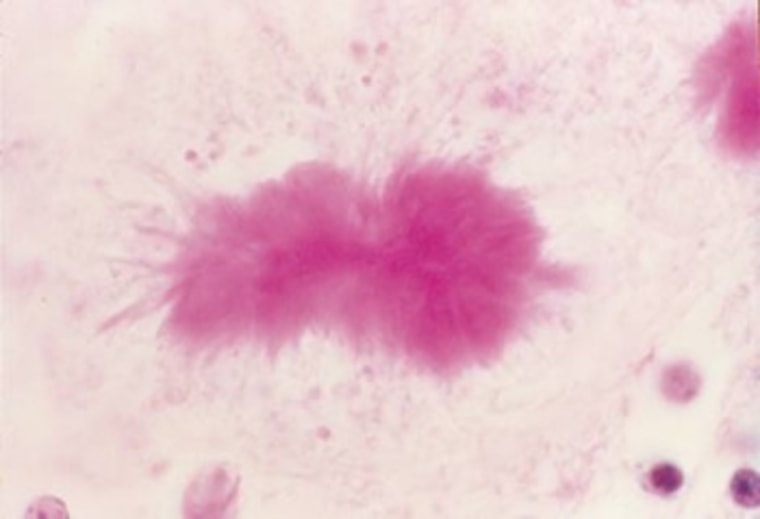

First, the test must be done postmortem; a cow must be killed and a brain sample scooped out. That sample is then checked for deformed prions, twisted proteins that cause BSE's fatal brain lesions.

Until last week, the USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, Iowa was the only U.S. facility approved for mad cow testing. Every sample in the nation was shipped there.

Under the new USDA effort, several public state labs will be allowed to check local samples and Ames will verify any initial positive results.

This local network will help reduce turnaround time, a crucial point for meat packers. Regulations announced Dec. 30 require carcasses of tested cows to be stored separately from other meat until tests come back negative.

New, more rapid tests will also help -– including one made by U.S. firm Bio-Rad that got a long-awaited approval last week. They can reduce holding times from two weeks to 24 hours or less. The new tests will bring U.S. practices into line with those elsewhere in the world. Most countries, including Canada, already use one of two rapid BSE tests.

Hundreds of thousands of tests come at a cost. BSE test makers price their kits between $10 and $16, and they estimate total costs per animal between $20 and $40. At those levels, the USDA plan could cost between $6 million and $12 million; it has set aside $70 million, taken from its Commodity Credit Corporation, for expanded testing.

The meat industry estimates far higher costs – perhaps as much as $100 per animal. Major slaughterhouses – notably the 40 large plants that will provide samples from healthy cattle -- will be forced to install additional storage freezers and train workers to help collect samples for meat that may never be sold.

“We’ve got an animal worth some money, and now it’s worth no money if it’s tested,” says Jim Hodges, president of the American Meat Institute Foundation, which represents meat packers. “It’s an added cost and burden throughout the system.”

Calls for private tests

Yet several smaller processors not only approve of the costs but are willing to pay for tests of all their cattle -- if it will convince foreign markets, notably Japan, to buy their meat again.

Creekstone Farms Premium Beef, of Arkansas City, Kan., petitioned the USDA to set up its own private lab. It estimates it is losing $60,000 to $80,000 a day due to Japan's halt on imports of American beef following the discovery in December of the first U.S. mad cow case.

The USDA has yet to respond to such requests. But it has repeatedly resisted any effort to allow testing beyond its own efforts. After Creekstone’s request, the agency politely reminded packers that private tests could warrant criminal action.

Private labs have offered to help, too, despite the USDA’s preference for public facilities. Rep. David Obey, D-Wis., recently asked Veneman to allow a medical complex in his district, Marshfield Clinic of Marshfield, Wis., to help in testing.

The clinic already performs animal-health tests and works with local meat processors on private food testing. Yet Marshfield has been rebuffed by the USDA before – when Wisconsin asked the clinic to participate in surveillance for chronic wasting disease, a fatal ailment in deer similar to BSE.

Combining public and private lab efforts, says Dr. Frances Moore, director of the clinic’s veterinary diagnostic services, has long been a staple of human disease surveillance at the Centers for Disease Control.

“It would be easy to bring this into our testing regimen,” says Moore.

Other members of Congress have endorsed private tests as a means of improving the chances of finding any additional cases.

"We think that as many tests should be done as possible if you're going to protect the food supply and protect the industry," says Rep. Maurice Hinchey, D-N.Y. "All you have to do is have a substantial outbreak of this stuff in the country and it's going to be very injurious to the industry."

Yet major meat packers seem dismissive of private tests. When asked if the tests could augment safety, Hodges responded, “I’m just not going to comment on that one way or the other, because I don’t think this is germane to the issue of a USDA surveillance program.”

Surveillance or food safety?

The gap between surveillance and food safety goes a long way to explain why Canada and the United States test so few cows, compared to many Western nations.

Government and industry officials vehemently resist suggestions the tests keep consumers safe. Instead, they argue, shoppers are protected by rules like those put in place last December, which banned from human consumption so-called risk materials – such as brain and spinal cord – from older animals. “It’s not a food safety test,” DeHaven said last week. “It’s a surveillance test.”

Officials also believe universal testing belittles the value of targeted surveillance. “Unless you prove that you haven’t got it, everyone will think that you have got it, which is a bit unfair, I think,” says Paul Kitching, director of Canada’s National Center for Foreign Animal Disease in Winnepeg. The center, which coordinates Canada’s BSE testing, will test 8,000 cows this year out of 3.7 million slaughtered.

Yet elsewhere, consumer safety is considered a perfectly acceptable reason for broad testing. During its crisis, Britain implemented nearly universal testing to show its herd was no longer widely infected and its meat was safe to eat. Japan, after initially spurning calls for a surveillance program, in 2001 adopted universal testing as a food-safety measure after it found its first case.

In Switzerland and Germany, testing helped reassure a nervous public; both have accepted the use of private labs and beef producers often pay for added testing.

In 2000, German meat packers paid a small private lab, Bovinia GmbH, to certify their meat BSE-free. Just weeks after the Bavarian regional government forced Bovinia to stop, government labs using the same Prionics tests uncovered the country’s first mad cow case.

The meat-buying public was scandalized; key government ministers resigned. As German consumers shied away from beef, more slaughterhouses started testing their animals and offering safety guarantees. Comprehensive testing was in place less than two months later. Private labs were quickly certified.

“You went from surveillance testing to systemic testing … overnight,” says Brad Crutchfield, vice president of life science at Bio-Rad, which makes most of the tests now used in Germany and Japan. “The only way you could respond to that was private testing.”

When consumers worry

The major difference from the U.S. experience? In other countries, consumers quickly shunned beef after the disease was found. German beef sales dropped more than 40 percent. France’s initially dropped over 50 percent.

By contrast, U.S. beef demand has remained high, even as export markets have dried up. This remains the case despite calls by U.S. consumer advocates for testing as a food safety measure and warnings about loopholes in the Food and Drug Administration’s 1997 rules that limit the use of mammalian protein in cattle feed – a key factor in BSE outbreaks. “We should really be concerned with what’s coming through now,” Hansen says.

U.S. testing plans might change if new technologies can be successfully developed, notably a test that would check cows before they are killed.

But major changes are unlikely to come unless Americans stop eating beef. Other countries’ experiences make clear big steps are usually prompted not by scientific risk assessments, but by fear.

“It becomes, basically, what the people want,” says Prionics’ Rupp, “and what they are ready to pay for.”