Every so often there is an obnoxious smelling stretch of road where even rolled up windows can't help. Driving through becomes an exercise in breath-holding. Now a group of Danish researchers is working on perfecting a bacteria-filled filter to stop stench at the source.

"Some bacteria are specialized in transforming a single compound," said Jeppe Lund Nielsen, an associate professor of biotechnology, chemistry and environmental engineering at Aalborg University in Denmark.

Nielsen and his colleagues are studying the microbiology inside a specialized odor-treating filter to improve its effectiveness.

NEWS: Humans Stink More Than Other Animals

"We're basically looking for the good guys and trying to promote them," he said.

Nielsen explained that sulfur compounds produced industrially are what we find most nauseating. These compounds can wrinkle human noses with their cabbage-like stench at less than a part per billion.

Along with a team that included Danish Technological Institute consultant Sabine Lindholst, Aarhus University associate professor Anders Feilberg, and University of Waterloo assistant professor Josh Neufeld, Nielsen focused on an advanced European biofilter.

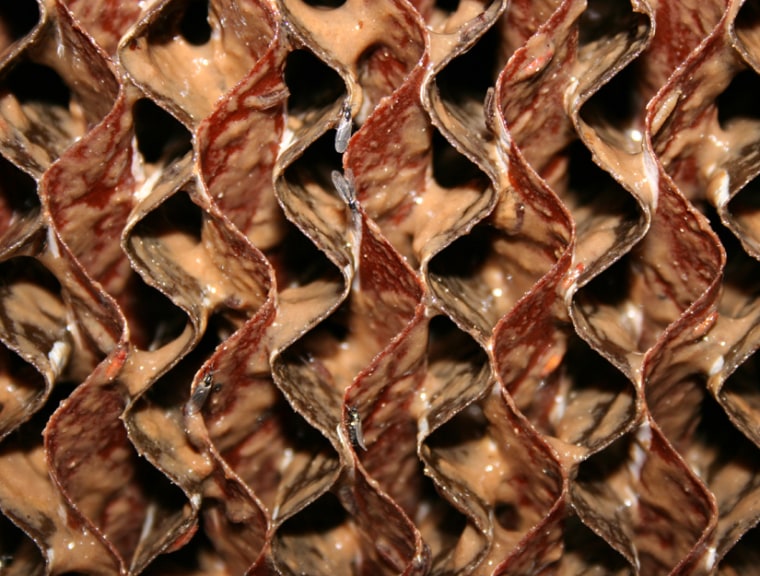

The filter contains corrugated cardboard filled with bacteria that are placed inside machines. A large amount of air from the industrial site is then pumped through the machines hourly, and a water rinse provides optimal moist conditions. As the air flows through the machine, the bacteria process the smelliest — and most toxic — compounds.

SCIENCE CHANNEL: Quiz: Facts about Noses

"If the filter is designed correctly, they can take up 80 or 90 percent of all the compounds that are passing through," Nielsen said.

Although this type of biofilter has been commercially available for several years in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands, Nielsen said that only a select group of farms have them. He added that the filters have been subject to periodic breakdowns and they can be costly.

"Farmers do not want to pay too much for cleaning the air," Nielsen said. "It's a tight business."

NEWS: What Does Anger Smell Like?

Like a business that has lazy workers, the bacteria don't all perform at the same level. By studying the physiology of these organisms, Nielsen and his colleagues want to help stabilize the filters. The group published their latest findings recently in the scientific journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology, where they identify problem-causing microorganisms that need to be weeded out from the effective bacteria.

Nielsen said he expects the filters to become more widely used in the future. Danish pig farming operations, animal rendering plants and fish processors have started using the filters. Already, with better efficiency and improved design, the filters are getting close to costing less than a dollar per pig to remove most odors it produces.

"It is a technology that can be transferred to many different industries," Nielsen said. "Even sewers can easily be relatively easily mounted with these air filters so they don't smell."

Duke University civil and environmental engineering professor Marc Deshusses specializes in using microorganisms to get rid of pollutants. He noted that the Danish group's journal article is one of numerous related articles in an active field. However, he did find their description of a vertical filter design compelling.

NEWS: Stink? Neanderthal Noses Didn't Notice

"The air passes horizontally through the active layers and you can have different treatment zones with different microorganisms, and that's interesting," he said.

The current body of knowledge to make such filtration systems more efficient is still lacking, but that's only one side of the picture, Deshusses said. In the United States, requiring all odor-producing industries to add filters would be a politically challenging, and potentially costly, prospect.

Deshusses agrees with Nielsen that research into making odor-treating biofilters cheaper and more efficient is crucial for a greater deployment of the technology. "In an industry like the pig industry where the margins of profit are extremely tiny, this is extremely important," he said.

Increasing population density means that residents are more likely than ever to live near odor-producing operations. Nielsen said several Danish rendering plants that process slaughterhouse waste were receiving frequent complaints from neighbors over the strong smell.

Then the plants installed bacteria-filled filters, Nielsen said. "They hardly get any complaints from the neighbors now."