Russia's botched Mars probe mission Phobos-Grunt is fast approaching a fiery death, with just one or two days remaining before it falls from space, experts and Russian space officials say.

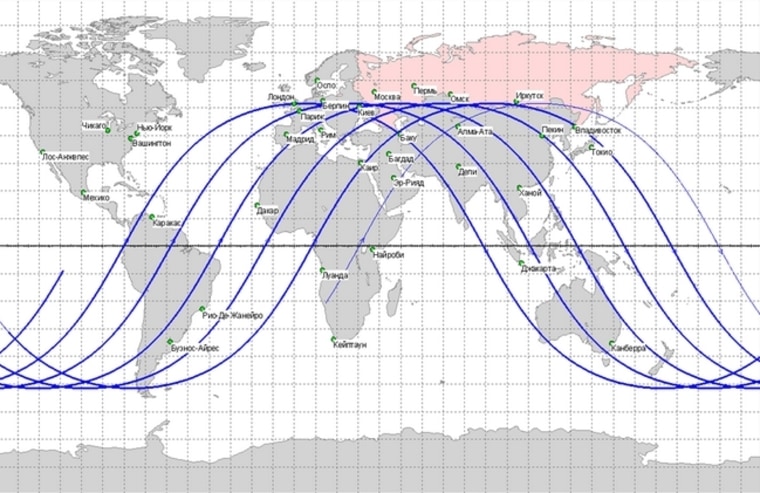

"The European Space Agency's current re-entry prediction for Phobos-Grunt … points to the early evening (Central European Time) on Sunday, Jan. 15, with an uncertainty of plus/minus five orbits," equal to plus or minus 7.5 hours, Heiner Klinkrad, head of the space debris office at ESA’s European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, told Space.com in an email Saturday.

A statement from Russia's Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos) also pegged Sunday as the crash day for Phobos-Grunt, but went even further. According to the statement, released in Russian, the 14-ton spacecraft filled with fuel is expected to fall on Sunday and may crash in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Chile.

Russian space officials pegged the potential crash time as occurring at about 4:51 p.m. ET Sunday, although major uncertainties still remain. There is a chance the spacecraft could fall earlier in the day, oron Monday.

Falling Russian Mars probe

ESA and a host of other space agencies and organizations have been closely monitoring the decay of the doomed Russian spacecraft. [Infographic: The Fall of Russia's Doomed Phobos-Grunt]

Russian space agency officials say they expect that, at most, 20 to 30 fragments of Phobos-Grunt may survive the fiery re-entry and reach Earth's surface.

But given that most of Earth's surface is covered with water, the odds that these leftovers — with a predicted total mass of less than 440 pounds (200 kilograms) — would fall onto dry land is very small, scientists say.

Russia launched the Phobos-Grunt mission on Nov. 9. The spacecraft was designed to fly to Phobos, one of two moons circling Mars.

Once at Phobos, the space probe was expected to collect samples from the Martian moon and then return them to Earth in 2014. However, shortly after launch, the spacecraft failed to boost itself out of Earth orbit to begin the trip to Mars.

Packed with toxic fuel

One unique aspect of the Phobos-Grunt re-entry is its large cache of onboard fuel.

While the dry mass of the wayward satellite is just 2.5 tons, the probe totes about 11 tons of toxic propellant, which went unused when the craft became marooned in Earth orbit and didn't head outbound to Mars. [Photos of the Phobos-Grunt Mars Mission]

Orbital debris experts suggest that Phobos-Grunt's fuel tanks, reportedly made of aluminum that contains unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine, or UDMH, will explode high above the Earth. Those heat-succumbing tanks would therefore release the load of propellant to burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

"The 'it just burns up' issue remains, invisible frankly," said Martin Ross, director of The Aerospace Corp.'s Center for Launch Emissions and Atmospheric Research in El Segundo, Calif.

"What is needed is a full accounting of the material that gets vaporized and re-condenses into small particles that may remain in the upper atmosphere for many years," Ross told Space.com. "Some of these particles may influence chemistry, since the vaporized materials are exotic in some cases, in that region of the atmosphere in subtle ways. It remains a question mark."

Flying in space is hard

Phobos-Grunt is also outfitted with a nose-cone shaped descent vehicle wrapped in a thermal protection system. It was meant to haul back to Earth samples collected at Phobos. That hardware was designed to sky-dive through Earth’s atmosphere to a hard landing without parachute in the Sary Shagan missile test range in Kazakhstan — if the Mars mission achieved success.

Nestled inside that re-entry sample capsule is the Planetary Society's tiny Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment (LIFE) biomodule, which carries a select set of microorganisms.

"Trackers won't be able to predict where debris may fall until just a few hours before the event, so it’s impossible to say whether the biomodule will be recovered," the Planetary Society said in a statement.

“What we’ve seen is heartbreaking reinforcement of an oft-repeated maxim. Space is hard! We are disappointed that our remarkable test of the hardiness of living organisms will not get the 34 months in deep space we had hoped for," said the Planetary Society's chief executive officer, Bill Nye, also known as the Science Guy.

"We also offer our condolences to the China National Space Administration; it's their first Mars mission and a disappointment," Nye added.

Like LIFE, China's Yinghuo-1 orbiter hoped to catch a ride to Mars on Phobos-Grunt in order to study the Red Planet.

Crash from the past

Russia has a bit of history regarding satellites falling from space and tumbling onto land.

Due to a propulsion system failure, the Cosmos 954 spacecraft — a Soviet nuclear-powered radar ocean reconnaissance satellite — fell into Canada's Northwest Territories in January 1978. It had been in space for only four months.

Large amounts of radioactive material from the satellite's fall were scattered from Great Slave Lake into northern Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Subsequently, a joint U.S.-Canadian cleanup operation picked up roughly 0.1 percent of Cosmos 954's power source. The spacecraft's nuclear reactor worked on uranium, enriched with isotope of uranium-235.

Canadian authorities determined that all but two of the Cosmos 954 fragments recovered were radioactive. Some fragments located proved to be of lethal radioactivity.

The spacecraft's plummet into Canada also marked the first time that the adjudicative process built into the United Nations' Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects was put to the test.

Canada's claims against the Soviet Union added up to more than $6 million. In 1981, the Soviets coughed up $3 million to settle the Canadian claim of reimbursement.

Unlike the Cosmos satellite, Russia's Phobos-Grunt is a solar-powered spacecraft. One instrument on the probe does carry a small amount of the radioactive element cobalt-57. However, Lev Zelenyi, director of the Space Research Institute in Moscow and chairman of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Solar System Exploration Board, has stated that the amount contained in that instrument is less than 10 micrograms and no significant problems are anticipated.

Standby alert

As Phobos-Grunt draws closer and closer to its fiery finale, a worldwide team of skywatchers is on standby alert in the hopes of spotting the fall.

"Experienced observers know that the probability of seeing any given satellite re-entry is very small, so they maintain very low expectations," said Canada-based Ted Molczan, a leader in the citizen network of observers. "Those who are keen to observe one [a re-entry of space hardware] will monitor the trend in the decay estimates.

"If it appears that re-entry will occur at about the time Earth’s rotation drags their location through the plane of the orbit, then they may go out and have a look, still fully expecting to see nothing, but knowing they have maximized their personal odds," Molczan said.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of last year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for Space.com since 1999.