A new look deep into the heart of our Milky Way galaxy comes closer to the central supermassive black hole than ever before, promising a way to see the very shadow of the mysterious object in coming years.

In the study, radio telescopes provided the best measurement yet of the diameter of a chaotic region of emissions surrounding the supermassive object.

The black hole, which holds a mass equal to nearly 4 million suns, was previously estimated to be about 14 million miles (23 million kilometers) across, much smaller than the orbit of Mercury around the sun. It can't be seen, because everything that approaches it, including light, is swallowed. But on the way in, matter is superheated to millions of degrees, generating emissions in many wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays.

Astronomers have for 30 years sought to learn exactly what causes the radio emissions and how near to the black hole they originate. The radio-emitting region is no more than 186 million miles (300 million kilometers) across, or less than the diameter of Earth's orbit, the researchers reported Thursday in the online edition of the journal Science.

Mysteries remain

"We don't know yet the complete nature of the radio emitting region, but as a result of our measurement we now have a tight constraint on its size," said Geoffrey Bower of the University of California-Berkeley. "We are much closer to seeing the effects of a black hole on its environment here than anywhere else."

Bower told Space.com that the radio emissions might originate from material that is falling onto the black hole, or perhaps they are spawned by a jet of stuff flowing away from the black hole at a significant fraction of the speed of light.

Further observations may solve that remaining mystery, he said.

For now, the new observations come closer to a black hole -- as measured in relation to the presumed size of the given black hole -- than any previous, Bower said. The primary work was done with the National Science Foundation's Very Long Baseline Array of telescopes.

Blurry vision

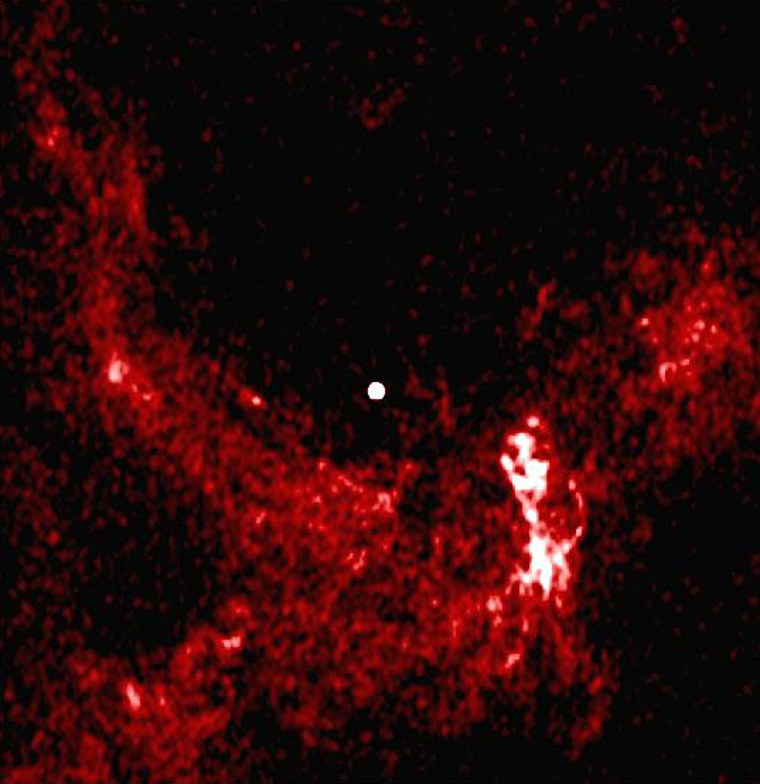

The radio-emitting region is called Sagittarius A* (meaning A-star). It was discovered in 1974 and later determined to be associated with a central, supermassive black hole. The whole setup is about 26,000 light-years from Earth.

The area is shrouded in dust, so visible-light telescopes can't study Sagittarius A*. Radio waves penetrate the dust but are scattered by the turbulent, hot gas in the area. The astronomers said this scattering had frustrated previous attempts to peer into the very core of the action. Bower likened the task to trying to spot a yellow rubber duck through the frosted glass of a shower stall.

To cut through the cosmic fog, the team employed higher radio frequencies, which correspond to shorter wavelengths. They also used longer wavelength observations to determine the effects of the scattering, then removed those effects from the short-wavelength data.

"After 30 years, radio telescopes finally have lifted the fog and we can see what is going on," said fellow investigator Heino Falcke of the Westerbork Radio Observatory in the Netherlands.

The researchers say the new observations rule out some less popular ideas for the cause of the radio emissions.

And there is room for improvement, Falcke and Bower say, by using even shorter wavelengths to drill down to the cutoff point -- the outer sphere of the black hole -- and essentially see a shadow of the immense dark object. Such an observation was proposed, based solely on theory, by Falcke and other colleagues more than four years ago.

"Imaging the shadow of the black hole's event horizon is now within our reach, if we work hard enough in the coming years," Falcke said.