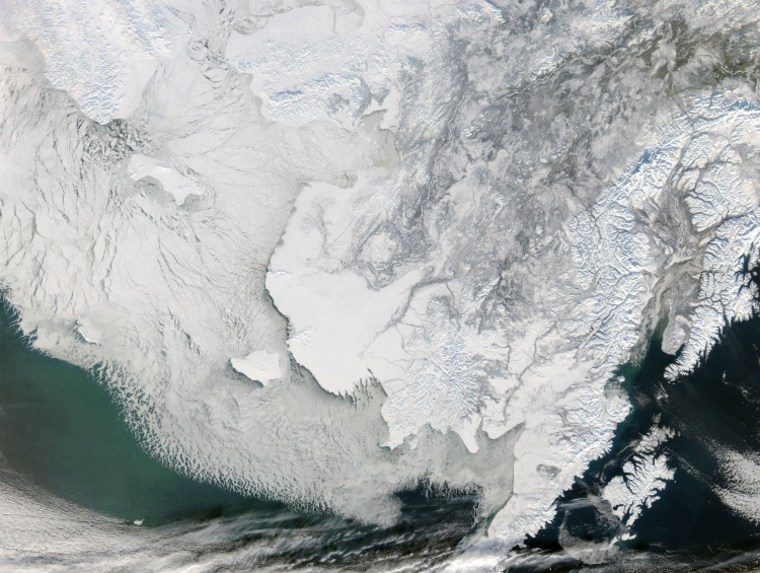

Humans have gotten pretty good at monitoring Arctic sea ice from afar. Since the end of the Reagan era, watchful satellites have measured the reach of the ice cover that marches across Arctic seas each winter and recedes each spring.

And since satellites started sending data back in 1979, scientists have watched the total area of annual ice cover steadily decline. The observation has piqued a flurry of interest in what the future holds for the Arctic and its disappearing ice — one of the loudest signals of global climate change.

"Satellite measurements are very good at telling you what percentage of the area is covered with sea ice," said Victor C. Tsai, an assistant professor of geophysics at Caltech.

Yet satellites have their limitations, said Tsai, who found that by looking at data from seismic stations — suites of instruments best known for measuring earthquakes — scientists can learn about the quality of sea ice.

"We think we can measure something to do with how strong the ice is," he told OurAmazingPlanet. "In order to make predictions about the future, you need to know the strength of the sea ice, and not just what percentage is covered."

Seismic sea ice signal

Like many discoveries, this one came as something of an accident. Tsai was examining data from seismic stations to be sure they were functioning properly, when he noticed something strange in the numbers from two stations near the Bering Sea.

"There was a lack of energy from about December though May," he said, a time when most seismic stations in northern climes usually pick up lots of energy — or ground shaking — because winter storms whip up waves that pound Arctic shorelines.

At first he and his collaborators thought the stations were malfunctioning, but the numbers revealed the same pattern, year after year.

"We tried to understand why that was, and we saw, oh yeah, this ties into when you have significant sea ice around those stations," he said. Which made sense, since it's known that sea ice dampens the vigor of ocean waves.

After further investigation, Tsai found a way to mathematically link the seismic data with how packed or broken up the ice is. The research was published in the Nov. 19, 2011 issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Short and long term

Tsai emphasized that the methodology is still young, and he's working to fine-tune the math. In addition, a larger network of seismic stations would be required to cover more of the polar regions and make projections of how sea ice might fare in the future, an important part of climate change forecasts.

"Right now we're much better poised to make shorter predictions — the next week or two — and it's much more difficult to make predictions for the more distant future," Tsai said.

However, there's one group that would likely be very interested to learn about the strength of sea ice a few weeks in advance — the growing number of ships crisscrossing Arctic seas.

"I would say that, at least immediately, it would be easier to help the shipping community," Tsai said.

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.