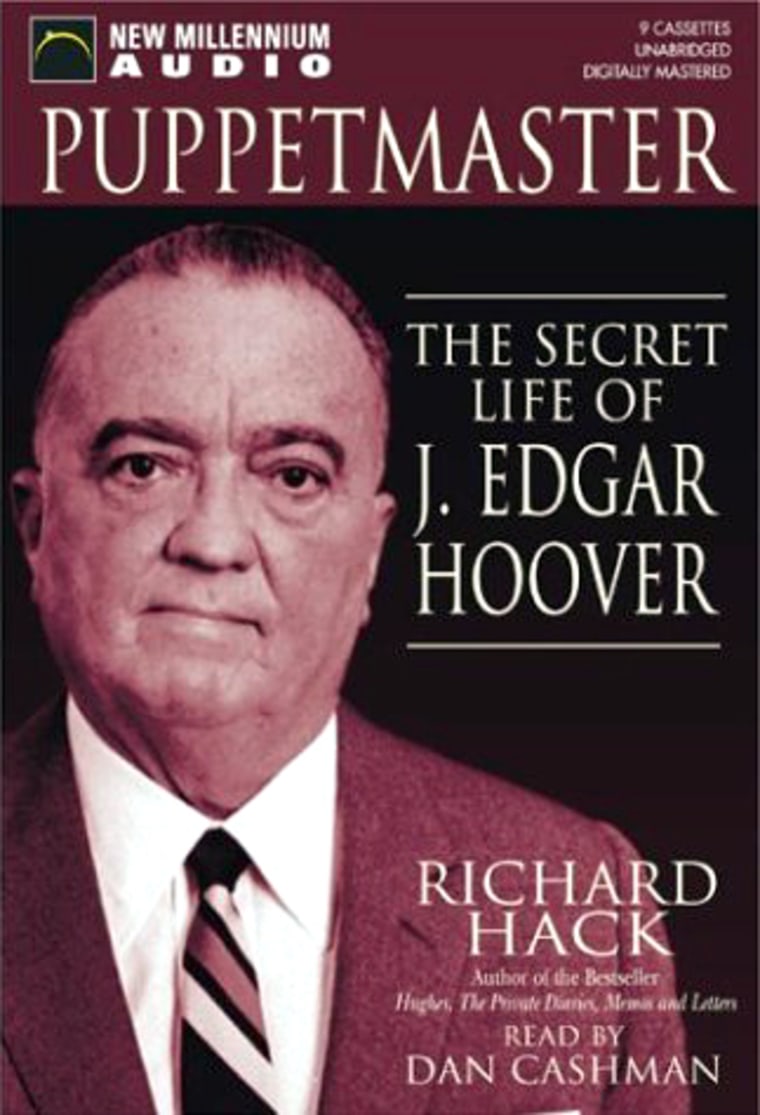

He was one of the most powerful men in the United States, serving eight presidents. He was also one of the most controversial, perhaps even more so after his death, when stories began to appear about the secrets of his private life. But were those secrets more fiction than fact?Author Richard Hack wants to set the record straight about FBI icon J. Edgar Hoover. Read an excerpt from his book, "Puppetmaster: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover," below:

Prologue

Death of an Icon

May 2, 1972. 4936 Thirtieth Place NW, Washington, D.C. There was an unnatural stillness about the place, sucked dry of breath and emotion, the space thick and unmoving. Only the steady ticking of a mantel clock bore witness as an old man lay dying on the floor. Unconscious, in the master bedroom, he pulled at air in a futile struggle against the inevitable. Stubborn, obdurate, unwilling to accept his own mortality. But then, J. Edgar Hoover had always fought against the odds. This night, however, would be different. This night, he would lose.

By 7 a.m., the low morning sun was streaking through the closed kitchen window as Hoover’s longtime housekeeper, a black woman named Annie Fields, adjusted the venetian blind above the sink and began to prepare breakfast. She didn’t mind that her employer was fussy and preferred to think of her as a maid. The work was easy even if Mr. Hoover was not.

The breakfast menu never varied—two soft-boiled eggs (positioned just so in porcelain cups that Hoover had inherited from his mother), white toast with softened butter, and black coffee in a flowered teacup—served each morning at exactly 7:30. With clockwork efficiency, as the food reached the dining room table, so too would Hoover. He would have risen an hour earlier, spent a cursory 15 minutes riding his Exercycle, showered, dressed, and watched Frank McGee and Barbara Walters on NBC’s Today to learn of any breaking news.

This morning, however, at the commanded half past seven, Hoover greeted neither the day nor his breakfast. He did not lumber down the steps and across the room, brushing his perfectly pressed suit as he looked for invisible lint. He did not give his usual “humph” as he molded his thick body into the mahogany chair at the far end of the table, nor did he purse his lips as he inspected his eggs for correct consistency.

By 7:45, in fact, the eggs were no longer even on the table. Annie had brought them back into the kitchen and placed fresh ones in rapidly boiling water on the stove top. Hoover’s two cairn terriers, G-Boy and Cindy, danced at her feet in anticipation of discarded toast, blissfully unaware that outside, Hoover’s chauffeur, Tom Moton, had arrived in his boss’s armored Cadillac limousine. As usual, Moton was early, leaving plenty of time for him to take a feather duster and remove pollen clinging to the car’s polished chrome grille.

When Moton learned that Mr. Hoover had failed to appear for breakfast, he was confused. “Not like Mr. Hoover, no sir,” he said as Annie rambled on. She hadn’t heard the shower running. No sound from the television, either. Nothing but the ticking of the mantel clock. Instinctively, the pair began to speak in whispers much like mourners at a funeral or congregants at church.

By the time James Crawford arrived at the back door a half hour later, Moton and Annie were openly fretting. Of the three, Crawford had worked for Hoover the longest, nearly 40 years. He had begun driving the man he called “the Boss” shortly after Hoover had been named head of the newly formed Bureau of Investigation, long before it was called the FBI, and had given up the position only five months earlier. He had reluctantly passed his chauffeur’s cap to Moton, his wife’s brother, hoping to spend more time with his family.

Yet, somehow, the Boss always found some chore he felt only Crawford could handle. This morning it was planting some fancy rosebushes, Zephirine Drouhin Antique Climbers according to their labels. The flowers had arrived the previous day from Hoover’s favorite nursery, Jackson & Perkins. The bare root bushes were laid neatly along the back of the house, arranged in precise order for planting. That was hardly surprising. Everything about Hoover was precise. He would have it no other way.

So when the Boss was nearly an hour late for breakfast, there was legitimate cause for concern. As the three servants huddled in the kitchen discussing the situation, it became obvious one of them would have to investigate, violating Hoover’s inflexible dictate that he was never to be disturbed in his room. Since Crawford was the only member of the trio who actually had a key to the bedroom, he was elected to explore the inner sanctum, darkened against prying eyes as if light itself were the enemy.

As Crawford made his way out of the kitchen, he moved through a maze of clutter he knew well. Winding through the living room and into the hall, Crawford’s mind raced as his feet fell heavily on the thickly padded stairs leading to the second floor. Surely, he thought, the Boss is merely sleeping. The rapid beating of his heart denied the truth of his unspoken words. Crawford knew Hoover had not overslept. Hoover never overslept.

Arriving at the top of the stairs, Crawford made his way down the corridor. He paused, but only for a second, then knocked, knowing there would be no answer, yet hoping that he was wrong. As he hesitantly tried the doorknob, he found the door unlocked. Strange. The Boss always locked himself in for the night, like some enigmatic treasure in danger of being ravaged.

Pushing open the door, Crawford moved into the dark space cautiously, uncertain. The black of the room was blanket thick, the windows blocked by shades and draperies and further covered by Chinese screens. Still, the light from the hallway was enough for Crawford to make out the bulky, unmoving form lying on the floor next to the bed. Reaching it, he found flesh cold to the touch, a body hardened by rigor mortis.

J. Edgar Hoover, the man who personified law and order in modern America, was dead. Wearing silk pajama bottoms and no shirt, he seemed smaller now—no longer the giant who, for nearly half a century, molded the Federal Bureau of Investigation and cast it in his own concept of purity and allegiance. Old and crumpled, Hoover had died as he had lived, alone and isolated.

As an adrenaline surge spiked nerve endings into motion, Crawford raced from the room, calling out to Annie, his fluttering heart threatening to fly from his chest and across the room. “The Boss is dead, on the floor!” he blurted out, knowing that life as he had known it for the past four decades was about to change. America was about to change as well, and for a few brief moments only the three black servants gathered excitedly in a Washington, D.C., kitchen were privy to the fact.

That changed quickly, of course, as calls were made—the first to Hoover’s constant companion and second-in-command at the FBI, Clyde Tolson. Tolson had to know first, for he, above anyone, would understand the implications. Since 1931, it was Tolson who had assisted the Boss as his chief cheerleader, administrator, organizer, and best friend. Too good of a friend, some said, as rumors of a homosexual relationship between the two men refused to die despite repeated denials.

Tolson himself had been in ill health for several years, with a serious heart condition and advanced high blood pressure. He also had suffered several strokes that left him partially paralyzed. Even as Crawford made the call, he wondered if word of Hoover’s death might finish the job and kill Tolson as well. Yet when the associate director of the FBI answered the telephone and heard the news, his reaction was not one of hysteria or grief but rather stoic silence, which Crawford attributed to shock.

The methodical Tolson called upon his FBI training one last time, and immediately reported the director’s death to Hoover’s titular boss, acting Attorney General Richard Kleindienst, 48 years old and only three months into the job. Placing the telephone receiver back on its hook, Tolson moved more out of habit than grief. As he had for the past 41 years, he crossed the room, exited his apartment, and rode the elevator to the building’s lobby to await Hoover’s limousine. Each morning the pair normally rode the short distance to the Justice Department together; each evening met again for dinner.

The previous evening, Hoover had cut short a photo session with a retiring agent to return with Tolson to his apartment, worried about the toll his assistant’s schedule had been taking on his health. Together they dined on Omaha Steaks, baked potatoes, baby peas—with vanilla ice cream for dessert. All of Hoover’s favorites. A perfect final meal, Tolson thought as he watched Moton drive up in the familiar armored Cadillac.

Washington, D.C., survives on its ability to spread news through a network as infinite as it is structured. Even as Moton was helping Tolson into the back seat of the black limousine, word began to spread systematically about the death of a man many considered to be indestructible. As each person received the shocking news, the groundswell grew in direct proportion to the importance of the man.

Annie Fields telephoned the Boss’s longtime executive assistant, Helen Gandy, catching the elderly woman just as she arrived at her office. It was Gandy’s first call of the day, recorded simply enough on the FBI log at 8:40 a.m. The entry listed simply “Annie,” with no indication of the tragic news she delivered. Gandy had worked for Hoover for 54 years, having first met the director when she was a file clerk in the Justice Department. Petite, attractive, and exceedingly likable, she became Hoover’s secretary at the age of 21, having assured her boss that she had “no immediate plans to marry.”

In keeping with Helen’s characteristic efficiency, she responded with calculated precision, calling the assistant to the director, John Mohr, to her office to inform him of Hoover’s death. She shed no tears; in fact, she was totally devoid of emotion as she related the news. The Boss would have wanted it no other way.

It was left for Mohr to tell his own boss, third in command Mark Felt, the deputy associate director. Despite his many years with the Bureau, Felt had held his current position for only 10 months, and, as such, had yet to prove himself to Clyde Tolson or Helen Gandy. Mohr, by contrast, was a Tolson confidant and had been an FBI agent for 33 years. Tolson knew he could rely on Mohr to handle the funeral arrangements and inform the various Bureau offices that their venerable leader was dead.

By the time Hoover’s longtime physician, Dr. Robert V. Choisser, was summoned to 4936 Thirtieth Place NW, President Richard Nixon had learned the news from his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, who had been informed by Kleindienst. “Jesus Christ! That old cocksucker!” the president was later quoted as saying of the man who many considered to have made Nixon’s run for the White House possible.

Choisser was equally surprised at the news, having only months before given Hoover a complete physical and a clean bill of health. It was 10 a.m. before the doctor arrived at Hoover’s colonial home to examine the body, nearly two hours after it was discovered. By then, Crawford had lifted it off the floor and placed it on the bed, draping a blanket over Hoover’s bare skin. Annie, who could not bring herself to look at the body, cleaned the bathroom but otherwise left the scene untouched.

Elsewhere on Thirtieth Place NW, it seemed like a typical spring morning. The sky was spotted with enormous clouds, more sharp edged than billowy, like cotton balls washed in alcohol. On the street, neighbors walked their dogs, blissfully unaware that an icon had fallen.

Inside Hoover’s home, however, serenity had given way to aberrant activity and constricted emotion. Clyde Tolson sat in the living room, occupying the same pale-green occasional chair he always used when visiting. Alone, introspective, his lips moving in silence, Tolson seemed oblivious to the federal agents who had just arrived to stand guard at the front and back doors under orders from John Mohr. In the kitchen, Annie Fields and Tom Moton sat drinking coffee, talking about their boss’s death in disbelief, while upstairs Choisser completed his examination and left Crawford to wait for attendants from Joseph Gawler’s Sons Inc. funeral home on Wisconsin Avenue to arrive.

By the time a nondescript station wagon pulled into the alley behind Hoover’s home just after noon, most of Washington and indeed much of the world were abuzz with the news of Hoover’s passing. They shared a common thread of shock, so permanent a fixture had Hoover become in law enforcement legend, so indelible his contribution. No one knew that more than Richard Nixon, who had been bickering for months with the FBI director over his failure to bend the law for some presidential “black bag” jobs — extracurricular and highly illegal break-ins that for years had been standard practice for FBI agents and were now forbidden by the agency’s head.

Though Nixon was as surprised as anyone at Hoover’s passing, he greeted the news with a sense of relief. It was the perfect solution. He no longer had to deal with the “Hoover situation” and could now appoint a more adaptable person in position to replace the deceased director. That afternoon, the president wrote in his private diary:

“He died at the right time: fortunately, he died in office. It would have killed him had he been forced out of office or had resigned even voluntarily.

“I remember the last conversation I had with him about two weeks ago when I called him and mentioned the fine job the Bureau had done on the hijacking cases. He expressed his appreciation for that call and also expressed his total support for what we are doing in Vietnam.

“I am particularly glad that I did not force him out at the end of last year.”

Yes, the perfect solution. And the perfect opportunity to sanctify the fallen icon with a state funeral. Nothing better than pageantry to bury any lingering rumors of animosity and showcase the president in an election year.

Nixon’s special assistant, Pat Buchanan, wrote the president’s official statement, which the president delivered to a subdued nation:

“All Americans today mourn the death of J. Edgar Hoover. He served his nation as Director of the FBI for 48 years under eight American Presidents with total loyalty, unparalleled ability and supreme dedication. It can truly be said of him that he was a legend in his own lifetime.

“For millions, he was the symbol and embodiment of the values he cherished most: courage, patriotism, dedication to his country and a granite-like honesty and integrity. In times of controversy, Mr. Hoover was never a man to run from a fight. His magnificent contribution to making this a great and good nation will be remembered by the American people long after the petty carpings and vicious criticisms of his detractors are forgotten.

“The FBI he literally created and built is today universally regarded as the finest law-enforcement agency in the world. The FBI is the eternal monument honoring this great American.”

Nixon ordered all flags on government buildings to be lowered to half-staff, except the one flying atop FBI headquarters. That one was to continue to fly at full staff as a symbol of Hoover’s courage “in resisting the vicious attacks on his organization.”

Others echoed Nixon’s praise, including Warren E. Burger, chief justice of the Supreme Court, who said that Hoover, “in dedicating his life to building the FBI . . . did so without impinging on the liberties guaranteed by the Constitution and by our traditions.” Senator Edward Kennedy added, “Even those who differed with him always had the highest respect for his honesty, integrity, and his desire to do what he thought was best for the country.” Senator Edmund Muskie, an outspoken Hoover critic, straddled the political fence by stating, “Some of us may have questioned some of his approaches in recent years, but no one could question his loyalty or dedication to his country.”

Not everyone saw Hoover’s passing as a loss, but few were willing to speak on the record for fear of retaliation. One who did was Martin Luther King Jr.’s widow, Coretta Scott King, who said, “We are left with a deplorable and dangerous circumstance. The files of the FBI gathered under Mr. Hoover’s supervision are replete with lies and are reported to contain sordid material on some of the highest people in government, including presidents of the United States. Such explosive material has to be dealt with in a responsible way. Black people and the black freedom movement have been particular targets of this dishonorable kind of activity.”

The secret files to which she referred were said to be filled with salacious goodies of scandal. They were the source of much of Hoover’s power, and their very existence had kept him in the director’s chair through 16 attorneys general. His was more than just a Washington record. It was the mark of a supreme diplomat who was said to have managed the files’ contents, revealing none of their details except perhaps to those individuals in a position to be hurt by their exposure: movie stars, writers, journalists, athletes, judges, congressmen, senators, even presidents. It was a silent form of blackmail: hardly subtle but enormously effective as long as none of the information ever became public knowledge. And for nearly half a century, J. Edgar Hoover saw to it that not a single word did. Ever. The files were so secret, in fact, that almost no one knew for certain if they even existed. But J. Edgar Hoover knew. That was enough.

Even before the president permitted Hoover’s death to be publicly announced, he ordered those files to be secured. The word was passed in regimental fashion: Nixon told Haldeman, Haldeman told Kleindienst, Kleindienst told Mohr. Mohr responded by sealing off the late director’s office at the FBI. “In accordance with your instructions,” Mohr memoed Kleindienst midday on May 2, “Mr. Hoover’s private, personal office was secured at 11:40 a.m. today. It was necessary to change the lock on one door in order to accomplish this. To my knowledge, the contents of the office are exactly as they would have been had Mr. Hoover reported to the office this morning. I have in my possession the only key to the office.”

Convinced, Nixon moved to capitalize on the publicity opportunity inherent in the director’s funeral. Awash with enthusiasm to gain the greatest television exposure possible as part of his reelection campaign strategy, the president informed Kleindienst that he wanted Hoover to be afforded a “proper and dignified state funeral,” complete with live coverage on all three commercial networks plus public television. Little consideration was paid to Hoover’s prior request to be buried in a Masonic ceremony, nor was any regard given to Helen Gandy, who had begun to make arrangements with the Supreme Council, 33°, Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, headquartered on Sixteenth Street NW. Rather, the mood at the White House was one of cautious celebration, a time for the president to publicly mourn the nation’s loss of a legend while privately planning to regain long-sought control of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Officially, it fell to the acting attorney general to appoint Hoover’s successor, though in reality Nixon would make the final decision. Anxious to preserve intact what he saw as the nation’s premier crime-fighting organization, Kleindienst placed a call to Cartha D. “Deke” DeLoach. DeLoach had served in the FBI for 28 years, rising to deputy director, Hoover’s lieutenant immediately under Clyde Tolson, before leaving in 1970 to join PepsiCo as a vice president. DeLoach knew the FBI as well as Hoover did, and he had the respect of his fellow agents, as well as a spotless reputation.

“Deke, I’m going to recommend to President Nixon that you be appointed interim director,” Kleindienst said to the astonished DeLoach. Though the onetime agent eventually turned down the offer, Kleindienst nevertheless placed DeLoach’s name into consideration for the position. It was just before noon, and Hoover’s body had yet to be moved from his bed.

The employees of Gawler’s funeral home were used to handling high-profile interments. Gawler’s had handled the funerals of John F. Kennedy, several Supreme Court justices, more than a dozen senators, and as many diplomats. Yet J. Edgar Hoover was different. The epitome of secrecy and intrigue, Hoover was as much a mystery as the bureau he created.

As the two men from Gawler’s walked in through the back of Hoover’s home and into his private sanctuary, they entered a museum that was caught in time and pressed for space. Against a conflicting background of dated wallpaper and contemporary furniture sat souvenirs of a privileged life: carved amber statues of the goddess Kuan Yin, porcelain Foo dogs on elaborate wooden stands, Ming vases, ivory Buddhas, a trio of Philip Kraczkowski bronzes, stuffed partridges converted into bookends, a half-dozen ivory elephants, a sterling silver oil lamp, a Peruvian drinking cup, and male nudes in marble, plaster, and porcelain — all showcased on mahogany tables draped in lace and sitting on Oriental carpets layered on top of one another and covering every inch of available floor space.

In the living room, the foyer, and along the staircase, the walls were the place of history: plaques awarded for achievement; pictures with presidents Harding, Coolidge, Roosevelt, Truman; and framed letters of commendation. At the bedroom door, a bust of Hoover stood guard.

The downstairs clutter and exaltation stood in marked contrast to the master suite, where traditional maple furniture and a two-hundred-book library gave the room a heavy, lived-in look that the remainder of the house lacked. If the four-poster double bed, chest of drawers with thick glass protecting its top, nightstands stuffed with pens and reading material, and an aging RCA color console television weren’t exactly Architectural Digest, they did at least speak to the man who escaped from public life here. The sole reminder that Hoover was someone special was found in a small statue of the FBI director, carved in wood and kept safe in a glass case on a table.

As the attendants from the funeral home placed Hoover’s body on a wheeled gurney, shielded him against prying eyes with a blanket, and carried him out through the back alley, the muted sounds of chaos were building on what passed for a front lawn. Television news crews competed with print journalists for position on the artificial grass that Hoover had installed four years earlier. The too-green Astroturf was an impulse purchase after James Crawford endured brain surgery in late 1968. As Hoover later explained to his horrified neighbors, he was worried that his chauffeur, who did double time as his gardener, might no longer be able to handle the Kentucky bluegrass that grew thick and manicured in his yard. Rather than find a new lawn man at cost, Hoover had the FBI install Monsanto Corporation Chemgrass. That same artificial surface was now crisscrossed with cables and sound equipment as the world’s journalists flattened Hoover’s budding flower beds in an effort to command a favorable location.

Their frustration upon learning that the body had been removed undetected was compounded by the announcement from local coroner Dr. James L. Luke that Hoover’s demise was caused by hypertensive cardiovascular disease—a common heart attack brought on by high blood pressure. That Hoover was neither being treated for high blood pressure nor taking medication to correct the problem did not seem to alarm Luke, who saw no reason to conduct an autopsy and permitted Gawler’s to prepare the corpse for viewing later in the evening.

Throughout the halls of the FBI, there was a palatable uneasiness. Not grief, really. More a sense that the enormous boat that had become the Bureau was suddenly rudderless, cast adrift. The fact that there was no storm did little to quell the apprehensions of those who remained aboard, leery of the future.

Even as both houses of Congress continued throughout the afternoon to deliver eulogies to the late director, voting that his body should lie in state in the Capitol Rotunda, Helen Gandy and John Mohr were dealing with far more pressing matters: the selection of a coffin, a burial suit, flower arrangements, and limousines, plus the preparation of Hoover’s family plot at the Congressional Cemetery where the late director’s mother, father, and baby sister were laid to rest. To complicate matters, the pair was getting little assistance from Clyde Tolson, who as acting director of the Bureau and the executor of Hoover’s estate was professionally and legally responsible for making many of those decisions.

Tolson’s structured world had crumbled. So accustomed was he to being in Hoover’s shadow that once the camouflage was removed, he felt naked and exposed, ill prepared to function and even less equipped to make a rational decision. The paperwork of the Bureau did not decrease because its director had died. There were memos to be signed, assignments to be made, meetings to be scheduled, and instructions to be delivered. Tolson’s secretary, Dorothy Skillman, had inherited many of her boss’s duties by default, signing his name to documents and referring decisions to associates, in particular John Mohr. It was therefore entirely possible that Assistant Attorney General L. Patrick Gray III had no idea that he was being shuttled from office to office in a political game of musical chairs when he arrived at FBI headquarters at three o’clock on Tuesday afternoon.

Gray moved easily through the crowd of reporters that had descended on Hoover’s office on the fifth floor of the Justice Department building that day. The onetime naval officer had returned to government service to serve under Nixon, and eventually was appointed an assistant attorney general for the civil division. Now working as Kleindienst’s unconfirmed assistant, Gray was eager to prove himself. He walked down the familiar halls looking for Tolson. Like everyone else in the Justice Department, Gray had heard about Hoover’s secret files, and that even he was mentioned in the contents of several. The president, of course, had his own file, and now Nixon wanted its contents protected by more than a new lock on the office door.

Dorothy Skillman didn’t have to do more than shake her head as Gray approached. Tolson’s door was open and his office obviously empty. What Gray didn’t know, and Skillman wasn’t saying was that Tolson wasn’t returning that day or any day. She had yet to receive official word, but she knew nonetheless. She was too efficient a secretary not to realize the effect the director’s death would have on her boss. Yet not even Skillman knew the toll it had taken.

As Gray moved down the hall toward John Mohr’s office, across town Tolson had just pulled himself away from the extraordinary scene that continued to unfold on Hoover’s front yard. Though no one had entered or left the house for more than three hours, the news crews kept their vigil as if watching the pot might make it boil. Reaching for his briefcase, the leather worn over years of service, Tolson looped his partially paralyzed left hand through the handle and pulled the case to his side.

It was an effort to move his tired legs, but to remain in the living room was even harder. He resented the stares of pity from the special agents on guard, as if he too had died right along with the director. Without comment, Tolson shuffled passed them toward the stairs and made his way to the guest bedroom on the second floor. He knew it well. When he was released from the hospital after his last stroke, he spent over a month being cared for in that very room.

As comfortable as an old shoe, with just the right amount of wear, the room was more Tolson than Hoover, an accommodation the director made to his old friend. Nowhere else in the house were there Navajo rugs, a souvenir from their trip to Arizona as were the pottery ashtray and Indian figurine. The wing chair had a faded slipcover, which Hoover had not replaced for it was Tolson’s favorite.

Sinking slowly to the edge of the bed, Tolson took care as he removed a single sheet of paper from his briefcase. It was written in the wobbling hand of an old man who could no longer control his fingers. He reread the words he had written several hours earlier, as if to remind himself they were still correct.

“I cannot continue to operate effectively in my current position, nor assume the responsibilities incumbent as Acting Director of the FBI,” the note began. Tolson’s resignation signaled the end of a career that had spanned nearly as many decades as that of J. Edgar Hoover. It was unfair that Hoover had died first, leaving him behind. He had neither the talent nor the desire for a life outside the shadow of his famous friend. Satisfied that the letter would suffice, he clumsily folded it in thirds, and returned it to his briefcase, snapping shut the latch on the leather strap for emphasis.

Back at the Department of Justice, Gray had reached the office of John Mohr, his patience running thin. He was being treated like a messenger boy, not as a representative of the president of the United States. Mohr sensed that the assistant attorney general was irritated even as he waved him to a seat, and found a hint of pleasure in Gray’s frustration. Rushing to complete the funeral arrangements for the late director, Mohr had little patience for interference from the White House, despite Nixon’s intention to turn the event into a national display of government pomp. He had even less patience when the real reason for Gray’s personal visit became clear. Gray wanted immediate access to Hoover’s secret files.

“I told him in no uncertain terms that there were no secret files,” Mohr later testified before a special House subcommittee.

The unscheduled meeting between the two men was as brusque as it was brief, yet it set the tone for future dealings between the White House and the FBI. The president’s reaction to the rebuff was one of contempt toward Mohr and distrust of his denial. This was a battle Nixon intended to win, and win quickly.

That evening Mohr made no mention of Gray’s visit as he stood next to Tolson in the chapel of Gawler’s funeral home. There, all eyes were on the open casket and the once powerful man inside it. In the rush to prepare the body, the makeup artists at the funeral home had washed Hoover’s hair, removing the dark rinse that the director had applied weekly to stave off time. His gray hair and eyebrows gave the corpse a unfamiliar pall, which, when coupled with Hoover’s puffy skin and too-pink rouge, made the body look like a poorly rendered wax figure. “He looked like a wispy, gray-haired, tired little man,” said one agent who had flown in for the viewing. “There, in the coffin, all the power and the color had been taken away.”

For Tolson, who was already suffering emotionally and physically, the sight of Hoover looking vulnerable and weak was unacceptable even in death. Those who arrived near the end of the evening found the coffin closed. And it remained closed throughout the days that followed.

The following morning at eleven o’clock, Hoover’s body was moved in the first act of an elaborate state funeral choreographed by the Department of Defense and coordinated by Colonel Vern Coffey, army aide to the president. More than 40 pages of documents detailed the preparations necessitated by the protocol, with all the timed scheduling of a shuttle launch.

It had rained the previous night and into the morning, the sort of quiet, gentle shower created by God for funerals. At the Capitol, an honor guard from all branches of the armed services lined the 35 steps leading to the Rotunda. And there was a quietness about the place, as if all of Washington had taken a deep breath at the same moment.

The hearse bearing the body arrived precisely at 11:25, and soldiers in dress uniform snapped to attention. The air was silvered, shadowless, as eight pallbearers struggled with the $3,300 brass casket. Lined with lead and covered in an American flag, the coffin weighed over half a ton, a fact evident in the pained expressions of those duty bound to make their slow march into the Capitol look effortless. Two suffered minor injuries in the process and were quietly hustled to the sidelines, but not before they slid the casket onto the black catafalque first used at the funeral of Abraham Lincoln. It was an honor previously reserved for presidents, military heroes, and congressmen. And now J. Edgar Hoover.

Inside the Rotunda, the nation’s leaders were assembled, tightly packed in their respective sections cordoned off by thick velvet ropes. The entire Supreme Court, swathed in their black robes of service; members of Nixon’s cabinet; senators; and congressmen—all poised to pay their final respects to a man most found intimidating even in death. They had come to laud his service, his integrity, and the FBI, which Chief Justice Warren Burger said was “an institution that is, in a very real sense, the lengthened shadow of a man.”

There were no notes of discord inside the Capitol, and Hoover’s sometimes stormy tenure as head of the FBI seemed forgotten in the rush to praise one whom Burger labeled “a man of great courage who would not sacrifice principle to public clamor.”

Even before the brief private tribute had ended, lines were forming outside the Capitol as the public solemnly waited to bid farewell to a national hero. Faces raw and moist with tears, they stood silently in the rain for one hour, two hours, four. Before the day was over, more than 25,000 visitors had entered the Rotunda to pay their final respects in an outpouring of respect that awed even veteran politicians. There was no mention of secret files or hidden sexual agendas. Rather, the motivation behind the vigil was one of loss and admiration. Perhaps as a validation of the skill with which Hoover spun his public image, he was cast as the most unique kind of civil servant: honorable, patriotic, of impeccable integrity.

At the White House, however, President Nixon held no illusion of Hoover’s character. His consuming love of gossip, publicity, and power were familiar faults. Only the extent of his knowledge was unknown. Without Hoover, the FBI was a powder keg of information likely to explode onto the headlines without regard for its victims’ celebrity status or political stature.

Moving quickly to gain control, Nixon reached into the ranks of malleable fronts and selected Nixon team player L. Patrick Gray III, the assistant attorney general, to head the Bureau on a temporary basis until the presidential election in November. Because Gray’s appointment would not be permanent, it required no congressional approval, thus denying the House and Senate an opportunity to scrutinize the selection. At three o’clock in the afternoon on May 3, as the rain fell over the Capitol dome, Gray accepted his appointment. Later at a press conference, White House Press Secretary Ronald L. Ziegler said that Nixon wanted to “name a man in whom he had complete personal confidence.” That Gray was a personal friend as well was sidestepped by Ziegler with, “I think you will find that Patrick Gray is not a political man.”

If not political, Gray was most certainly dogged as he returned to John Mohr’s office to question him once again about the location of the secret files — this time as Mohr’s newly appointed boss. Although the answer was the same, the discussion was not. According to testimony before a House subcommittee, Gray screamed that he was “a hardheaded Irishman” whom nobody pushed around. Mohr countered that he was a “hardheaded Dutchman” who could stand his ground against anyone.

As echoes of the argument traveled the length of the corridor, Helen Gandy paused briefly before turning back to her work, sorting through Hoover’s “Official and Confidential” files kept in her office. Not secret files, per se; but rather private ones, yet scandalous enough to be separated out from the central filing system because of their sensitive nature.

When Gray passed Gandy’s desk after leaving Mohr’s office, he paused long enough to question her actions. The efficient executive assistant was upfront, informing him that she was separating Hoover’s private files from those that were FBI property, on instructions from Clyde Tolson. Out of innocence, naiveté, or stupidity, Gray never asked to examine the files. The mere mention of Tolson’s name made him blanch.

After receiving his appointment as the new FBI director, Gray’s first call had been to Tolson. More than just a courtesy, he intended to make it clear that a new order of authority was now in place at the Bureau. Tolson, comfortably ensconced in Hoover’s home, refused to take Gray’s call and instead made one of his own to Helen Gandy.

In his last official act as associate director of the FBI, an organization to which he had devoted his life for the past 44 years, Tolson instructed Hoover’s executive assistant to destroy the director’s files, and protect and preserve his image forever. Gandy had, in fact, already begun the task, per protocol established by the director himself in the event of his death. Now satisfied that his work was done, Tolson authorized release of his letter of resignation, hung up the phone, and poured himself a whiskey from Hoover’s private reserve.

Helen Gandy smiled sweetly at Gray and turned back to her work, dismissing the new acting director. He was an interloper into her world and that of the FBI. A pretender to the throne. To her, he would never be anything more.

The following morning, several thousand FBI agents, police officers and other members of law enforcement lined the route from the Capitol to the National Presbyterian Church, saluting as the hearse carrying the fallen FBI director rolled past surrounded by 11 motorcycle patrolmen. Television cameras broadcasting the state funeral followed the cortege through the streets of Washington and watched as an honor guard of body bearers unloaded the casket in front of the white stone church built only five years earlier.

President Richard Nixon, leading the eulogies, called the civil servant “a giant [whose] long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to the country which he loved so well. . . . He became a living legend while still a young man, and he lived up to his legend as the decades passed,” Nixon said in eulogy. “He personified integrity; he personified honor; he personified principle; he personified courage; he personified discipline; he personified dedication; he personified loyalty; he personified patriotism.”

Clyde Tolson and Helen Gandy watched from their seats at the side of the chapel, hidden from the 1,200 in attendance. Nixon had positioned himself; his wife, Pat; Patrick Gray; and former first lady Mamie Eisenhower in the first row of pews, directly in front of the television cameras.

As the eulogies ended and the chapel filled with the a cappella voices of the army choir, Tolson was helped into a wheelchair and out the side door to a limousine supplied by Gawler’s. He wanted neither pity nor attention, yet received both an hour later at Hoover’s graveside at the Congressional Cemetery. There J. Edgar Hoover was laid to rest in the family plot not far from the Anacostia River. Looking lost, confused, and deep in grief, Tolson received the flag that had graced Hoover’s coffin with a simple “thank you” after the short service. As James Crawford wheeled him to the waiting limousine, none among the mourners spoke. They simply watched in silence as Hoover’s most trusted friend and colleague disappeared behind a grove of maple trees. Only then did they retreat to their cars to brave the midday traffic in Washington.

Cemetery workers lowered Hoover’s 1,400-pound coffin into his burial vault, the bier mechanism straining under the load. Even as the first shovelfuls of dirt were cast into the grave, black children from the neighborhood began dancing around the tomb, removing yellow mums from the presidential wreath.

A cemetery worker yelled at the youngsters. “You leave those flowers alone now, hear? This here’s the grave of a great man,” he said. “Ya gonna learn ’bout in school,” he added under his breath, never realizing how right he would be. In the years to come, the story of J. Edgar Hoover would reveal a legacy unlike any other in this country’s history. And secrets — so many secrets. Secrets that were the source of his power and the well of intrigue that ultimately threatened to undermine democracy itself.