10 to 11:30 a.m.: When the Mars rovers touched down in January, dozens of journalists thronged to daily news briefings in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Von Karman Auditorium, a five-minute stroll from Building 264. JPL's museum, next door to the auditorium, was remodeled into a makeshift press room.

By March 11, things have wound down considerably: The press room has been dismantled, and the museum exhibits are being moved back into place. The news briefings were reduced to three times a week, then to just one a week. A full-size Mars rover replica still sits in the auditorium, but the weekly briefing has been moved to JPL's TV studio, in a small annex behind the auditorium.

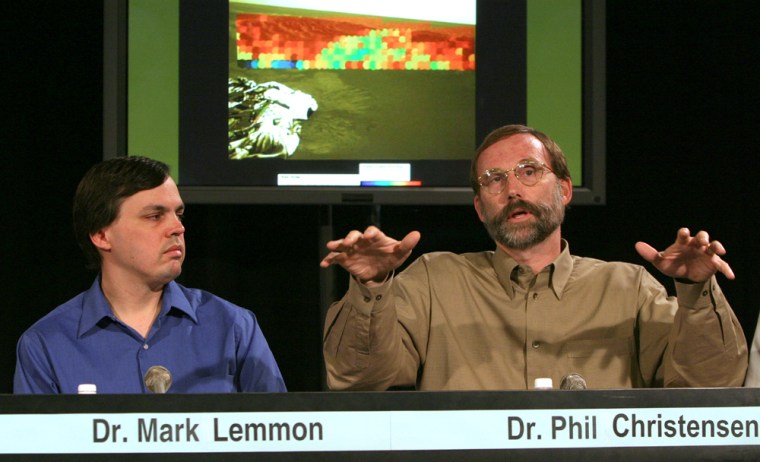

About a dozen journalists attend the March 11 briefing. Joining JPL's Matt Golombek on stage are mission manager Jennifer Trosper, rover planner Chris Leger and three visiting members of the science team: Texas A&M's Mark Lemmon, Arizona State University's Philip Christensen and the Space Science Institute's Michael Wolff.

Trosper declares both of the rovers to be in good shape, while Leger describes the challenges of guiding a rover to the crater's edge remotely. "If you tried to drive your car up here, you'd probably end up with a flat tire and a busted oil pan," he says.

Golombek focuses on Spirit's commanding view from the rim of Bonneville crater, "a place that no one had ever seen before from a vantage point like this." Lemmon shows off Spirit's sky pictures, including "the first image of the Earth taken from the surface of a planet beyond the moon." Wolff talks about his study of Mars' atmosphere.

Christensen talks about the prospects for finding gray hematite, a particular kind of iron oxide mineral whose presence would strengthen the case for ancient water on Mars. Data from Mars Global Surveyor indicated that Meridiani Planum should be brimming with hematite.

"The hematite was what brought us here," Christensen said.

He doesn't mention the cross-bedding. But one of the journalists calling in via a telephone link does.

"I see on the Web that on Sol 39 you took 120-some images with the microscopic imager of Last Chance, but nobody has said anything about what you discovered from looking at that rock," says Henry Bortman, managing editor of Astrobiology Magazine. "Did you see that cross-bedding? What does it tell you about whether these rocks were deposited in water? And if you still haven't answered that question, what will you be doing before you leave the crater to try and answer it?"

"I'll take a shot at that," Christensen replies. "Yeah, we did acquire a huge number of images. They are being processed and analyzed and put together with the Pancam. The team is looking very hard at that, trying to answer that question, and it's still far too early to say one way or another."

It's not a lie, but Christensen holds off from saying that the scientists suspect there was indeed cross-bedding, and that they're waiting for confirmation from the outside experts. The secret is safe.

Golombek addresses another open question: Scientists had considered sending Spirit down into Bonneville crater, but now that they've taken a look over the edge, they don't see any of the layered rock that would demand further study.

"It seems that the material that we see in that uppermost part of the crater is in fact the same material we've been traversing across," he says.

If there's nothing worth going into the crater for, Spirit would make its way around Bonneville's rim, then head for the hills to the east.

"There's been absolutely no discussion by the science team of whether or not to go down, there's been no discussion with the intrepid rover drivers about whether that would be a smart thing to do, considering we might not be able to get out," Golombek says.

After the briefing, reporters ask Golombek whether Bonneville was a disappointment. No, he answers. Spirit's observations in the coming days could still reveal something in the crater worth a closer inspection.

"This is what exploration is all about," Golombek says. "Why should I speculate, when in a week we'll know what to do?"

Two weeks later, the scientists will decide sending Spirit into the crater isn't worth the trip. Instead, they will point the rover toward the Columbia Hills, 1.4 miles (2.3 kilometers) away, for what is likely to be the longest trek of its mission.