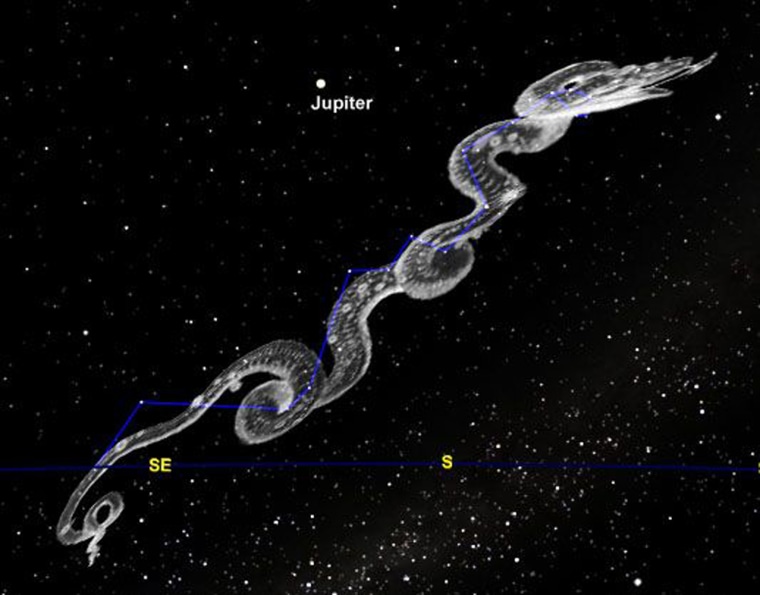

With the bright moon now completely out of our early evening night skies this week, we can look to the south to trace one of the most extensive of all star patterns: the long and mostly faint constellation of Hydra, the female water snake.

One of the more famous Hercules stories is how he killed a hundred-headed serpent known as the Hydra. Perhaps that’s why when the constellation of Hercules stands triumphantly overhead on summer evenings, the tail of the constellation Hydra is slithering out of sight below the southwest horizon.

(A male snake bearing the name Hydrus is visible only in Southern Hemisphere skies.)

Hydra, for Northern Hemisphere skywatchers, begins just below Cancer with a boxy shape of five stars representing the snake’s head, between Procyon and Regulus, and south of the faint Cancer the Crab. Its scraggly stream of dim stars then wriggles southeastward past its lone bright star — ruddy second magnitude Alphard — which appears brighter than it is because it has no competition star, hence it’s sometimes called the "Solitary One."

Hydra’s trail of faint stars finally ends in a distant tail below Virgo, reaching almost as far to the east as Libra the Scales. The entire snake, running from high in the southwest sky, over toward the south and finally down low to the southeast, is in view beginning after about 9:30 p.m. local daylight time.

Hydra is slithering underneath faint Sextans the Sextant, Crater the Cup, and brighter Corvus the Crow. Despite meandering across 95 degrees of the sky (and taking nearly seven hours to fully rise into view), it doesn’t include much of general interest. But the star Epsilon Hydrae is a multiple star system: a close pair of stars that take 15.3 years to orbit each other, with a third star orbiting around the close pair and taking about 650 years to make one complete revolution.

Tale of the Crow

Of the three smaller constellations sitting just above Hydra, by far the most conspicuous is Corvus, which on star charts appears as a small, moderately bright quadrilateral-shaped pattern of stars. Were we to add a fainter, adjoining star, the pattern would then resemble the battened mainsail of a Chinese junk.

Corvus is supposed to represent the unfaithful raven of the god Apollo. The bird was sent out with a goblet or cup for some water, but instead loitered at a fig tree until the fruit became ripe. He then returned to Apollo without the cup, but with a water snake in his claws, alleging the snake to be the cause of his delay. As punishment, the angry Apollo changed Corvus from silvery-white to the black color that all crows and ravens bear to this day. In addition, Corvus was forever fixed in the sky along with the Cup (Crater) and the Snake (Hydra), doomed to everlasting thirst by the guardianship of the Hydra over the Cup and its contents.

Crater the Cup is a small and rather faint figure, which corresponds quite closely to its name. Its stars indeed outline a goblet, but unfortunately they’re hard to distinguish when the sky is hazy or when there’s a bright moon in the sky.

Corvus also serves as a useful guide for anyone traveling south. Directly south of Corvus is Crux the Southern Cross, but one must go well south, down to Brownsville in Texas, or Miami, the Florida Keys and beyond to see this very famous southern constellation.

The obsolete Owl

Lastly, there is one other star pattern of note. It can be found on some older star atlases sitting complacently on the end of Hydra’s tail. It is Noctua, Vel Avis Solitaria or simply the Owl. Composed of nearly two dozen mostly faint stars, this night bird was sketched out in the sky in 1776 by a Frenchman, Lemonier, in memory of the voyage of the famed French astronomer Alexandre Guy Pingré to Rodriguez Isle.

Unfortunately for Lemonier and Pingré, today the Owl is no longer recognized as an official constellation, its dim retinue of stars belonging now to Virgo and Libra.

Ironic in a way, since there are a variety of different birds that inhabit the nighttime sky, yet the bird that is most associated with the night is not one of them!