Remember tabletop cold fusion, which harnessed the power of the sun in a glass of tap water? Or the motionless generator, which made free electricity from the air?

How about Sokalian quantum gravity or the sunflower clock?

No matter if you don’t. They were all just a lot of hot air, which has blown through science for centuries.

But what if you could start with a lot of hot air? What could you invent then?

Frank Polifka did just that, and he might well revolutionize industry and the environment.

‘Tornado in a Can’

Polifka, with no more than a high school education and a creative way of looking at problems, has been working on the Windhexe for 15 years. He calls it the “Tornado in a Can” — a system for safely harnessing the enormous power of a funnel cloud in a small industrial machine.

Scientists say they doubt that's what’s really happening, but there’s no doubt that whatever you put in the Windhexe — shoes, rocks, sludge, concrete, industrial waste — comes out the bottom as a superfine powder.

It’s a clean way to dispose of almost anything safely and cheaply, because there are virtually no polluting emissions. Industrial scientists say its uses could be limited only by the imagination.

And some imaginations are running wild. Pastors have circulated a church sermon that draws its lesson from the Windhexe, comparing the power of the “Tornado in a Can” to the power of God’s love. Conspiracy theorists, meanwhile, propound that the technology was given to mankind by aliens because it appears to create a product that produces far more energy than is put into it — what science fiction writers call a “perpetual motion machine.”

In fact, what the Windhexe is is a big chicken squisher, at least for now. Polifka is selling the Windhexe — quietly — through a company called Vortex Dehydration Systems, which got involved because its principals all come from the poultry industry, and Polifka offered them a way to safely and cleanly reprocess poultry waste.

A breakthrough under wraps

When Vortex demonstrated the Windhexe at Polifka’s farm a couple of years ago, he entertained a clutch of feature reporters by dumping cookies, diapers and a dead bird into it, all of which emerged as fine powders. The result: a burst of publicity that miscast Polifka as something of an eccentric amateur tinkerer, and a grumbly response from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which withdrew the company’s patent for more review. The patent wasn’t restored until early this year.

Polifka and his partners at Vortex have kept quiet ever since. Even now, they don’t like to divulge much in the way of an explanation of how the machine works. “Speed kills. Information too fast can kill,” said David Winsness, Vortex’s president.

For this article, MSNBC.com used only technical information the company has made publicly available, its 2002 patent application and the educated guesses of scientists who have no connection to Vortex or the Windhexe.

Spin, in the name of the law

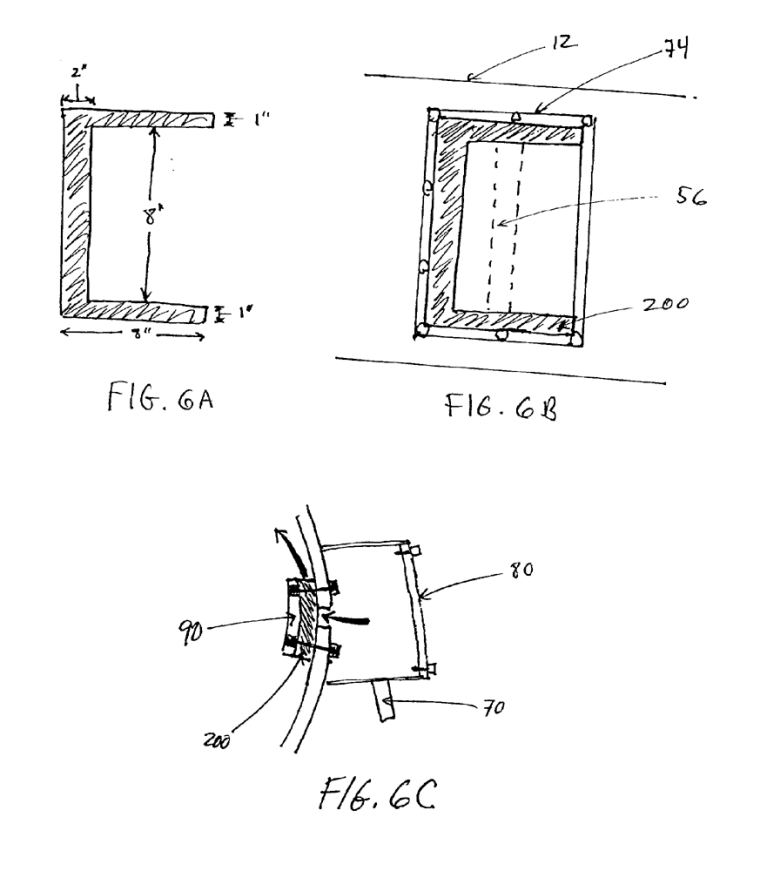

If it’s not violating the laws of physics, the Windhexe appears to have a rakishly outlaw attitude toward them. An upside-down cone just 8 feet tall, with no moving parts, it swiftly (and loudly) reduces pretty much anything to a powder of particles roughly a micron across — about 0.00004 of an inch, or one one-hundredth the width of a human hair.

The basic idea is not new — a device called the Hilsch Tube was dreamed up as long ago as 1928 to produce superheated air at one end and supercooled air at the other. But no real use for it could be found.

It took Polifka, who farms wheat and milo in Hays, Kan., to provide the practical function, and the ingenuity. He knew the machine should work, and it did. It's just that nobody’s quite sure how.

The Windhexe forces highly compressed heated air into four openings at the top; when those airstreams meet, Vortex says, they swirl about and essentially create a miniature funnel cloud, whipping around at incalculable speeds. And yet, the Windhexe generates so little heat that you can safely catch the resulting powder in the palm of your hand as it streams out the bottom.

“I've got to admit” the Windhexe is ingenious, said Harold Brooks, head of the Mesoscale Applications Group at the National Severe Storms Laboratory. But Brooks, whose title is a long way of saying he’s the federal government’s top tornado expert, is adamant that “calling it a tornado is a stretch.”

“It’s just a vortex,” Brooks said, based on his review of the Windhexe’s description on the company’s Web site. “... We’re just blowing stuff around in there.”

Brooks speculated that what is going on is that the highly pressurized air streams are banging particles together and against the sides of the Windhexe in a speeded-up version of the way lapidaries polish gems in a tumbler.

Other scientists said that as the air is forced down the funnel at the bottom, the pressure and speed have to increase proportionally, the same way a stream of water builds up pressure and shoots out farther from a hose when you put your thumb in the way.

“It may just be a very efficient way to knock things into walls very fast,” Brooks concluded. “Fast, but in a gentle way — not like a cannon into a wall.”

Waiting for markets to emerge

At first, Vortex emphasized the Windhexe’s utility in poultry processing, and even now, it markets the machine as being “strategically designed for the meat byproduct processing industry.” Animal carcasses and other byproducts that are processed and dried through the Windhexe result in a finished product that Vortex says retains significantly more of its nutritional value (for use in animal feed, for example) than if they had been dried in a heat system.

But the Windhexe could have scores of other near-revolutionary industrial applications, some of which the company is now exploring:

- Eggshells can be pulverized and collagen powder can be separated from the resulting material, producing a plentiful reconstitutable supply of the expensive protein “glue” that is the base for many cosmetics and medical applications, such as skin grafts and angioplasty heart-valve sleeves.

- A Windhexe is being used to dry lignite coal in Australia, leaving an easily disposable clean powder that doesn’t pump pollutants into the atmosphere.

- The machine can take the remains of processed animals, which frequently are dumped, and produce what the company calls highly nutritional “edible systems,” such as bouillon, powdered extracts and flavorings and dried soups, all manufactured cheaply and transported easily.

- The Windhexe could make a huge difference in the safe processing and disposal of hazardous animal, human and industrial waste. With a whir of the Windhexe, you could turn such waste it into a powder that takes up one-tenth the space in a landfill.

Vortex is concentrating for now on large industrial applications like those, but in its patent application, it told the government that eventually, the Windhexe could be used in pasteurization, in desalination of salt water or in “small grinders and dryers" (think kitchen appliances).

There’s no need for Vortex to create a demand or manufacture new markets. “Commercial product launches will follow each potential market found as their value to society becomes clear,” the company says. It has already begun licensing the technology to companies in other fields that can figure out ways to use it.

Is it really a “Tornado in a Can”? Well, no, it isn’t. But “it’s probably fairly efficient,” said Brooks, the tornado expert.

“If it works, it works.”