The phone call came like a bolt out of the blue, so to speak, in January of 2011. On the other end of the line was someone from the National Reconnaissance Office, which operates the nation’s fleet of spy satellites. They had some spare unused "hardware" to get rid of. Was NASA interested?

And so it was that when John Grunsfeld, the physicist and former astronaut, walked into his office a year later to start his new job as NASA’s associate administrator for space science, he discovered that his potential armada was a bit bigger than he knew. Sitting in a clean room in upstate New York were a pair of space telescopes the same size as the famed Hubble Space Telescope, but which had been built to point down at the Earth instead of up at the heavens.

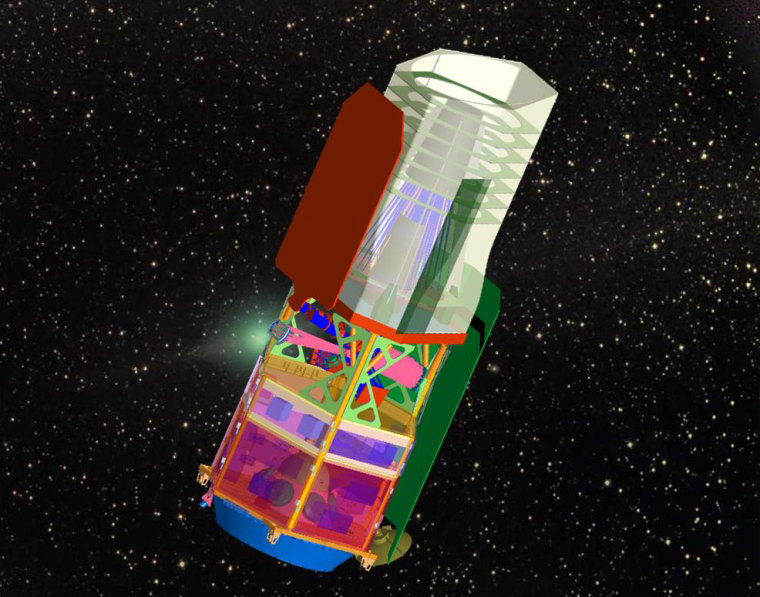

NASA, struggling to get human space exploration moving again, then spent the last year trying to figure out how good these telescopes were and what, if anything, they could be used for. Some people wanted to bulldoze them; others wanted to scavenge them for parts. Working in secret with a small band of astronomers for the last couple of months, Dr. Grunsfeld, famous as the Hubble telescope’s on-orbit repairman, has now come up with a plan, which is being presented to the public on Monday. It is to turn one of the telescopes loose on the cosmos pointing in its rightful direction, outward, to investigate the mysterious dark energy that is speeding up the expansion of the universe.

If the plan succeeds — and responsible adults in Congress, the Office of Management and Budget and the Academy of Sciences have yet to sign on — it could shave hundreds of millions of dollars and several years off a quest that many scientists say is the most important of our time and that NASA had said it could not undertake until 2024 at the earliest.

'Total game changer'

"This is a total game changer," said David N. Spergel of Princeton, who is co-chairman of a committee on astronomy and astrophysics for the National Academy of Sciences, which sets priorities for NASA and other agencies. Dr. Spergel was among a small group of astronomers who have been quietly studying the possibility of using the "repurposed telescope" under Dr. Grunsfeld’s direction.

Alan Dressler, of the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, Calif., said he was “really excited" about the proposal.

"We needed something that would have its own sort of logic and momentum," said Dr. Dressler, who will be reporting on the scientific potential of the NRO-1 telescope — as astronomers are calling it now — at a meeting at the National Academy of Sciences on Monday in Washington, the first step in the long process of turning an idea into an official project.

"It could put Americans back in the game," said Adam G. Riess, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who was one of three who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics last year, and who is eagerly awaiting details of the new plan.

For now, the two telescopes and some spare parts are still in their clean room at ITT Exelis, in Rochester. Michael Moore, who, as NASA’s acting deputy director for astrophysics, took the original call last year, has been to see them several times. He described their optics as "astounding."

Dr. Grunsfeld described the telescopes as "bits and pieces" in various stages of assembly, lacking a camera and other accouterments, like solar panels or pointing controls, of a spacecraft. "We can’t say what they were used for," he said.

A spokeswoman for the National Reconnaissance Office confirmed that it had transferred equipment it no longer had any use for, but would not elaborate.

"This is not something we’re going to talk about," said the spokeswoman, Loretta Desio, adding, "We’re hoping this becomes a NASA story."

'Stubby Hubbles'

The two telescopes have a 94-inch-diameter primary mirror, just like Hubble, but are shorter in focal length, giving them a wider field of view: "Stubby Hubbles," in the words of Matt Mountain, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, adding, "They were clearly designed to look down."

Dr. Grunsfeld said his first reaction was that the telescopes would be a distraction. "We were getting something very expensive to handle and store," he said.

Earlier this spring he asked a small group of astronomers if one of the telescopes could be used to study dark energy.

The answer, he said, was: "Don’t change a thing. It’s perfect"

Astronomers have lobbied for a space mission to investigate dark energy ever since observations of the exploding stars known as supernovae indicated that the expansion of the universe was speeding up, the discovery that won Dr. Reiss and two other American astronomers the Nobel Prize. The fate of the universe, as well as the nature of physics, scientists say, depends on the nature of this dark energy.

But a decade of wrangling between agencies and astronomers over money and technical specifications had resulted in no consensus on a mission until 2010, when a committee of the National Academy of Sciences that was charged with determining astronomical priorities cobbled together a plan that would do the trick. In its report, "New Worlds, New Horizons," the committee gave that mission the highest priority in space science for the next decade.

The $1.5 billion project was called WFIRST, for Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope. Among its virtues was that it would search for exoplanets — planets beyond our solar system. But NASA, hobbled by mismanagement of the James Webb Space Telescope, has said that it will have no money to launch WFIRST until 2024 or later, if all goes well.

Recently, to the disgruntlement of many American astronomers, NASA agreed to participate as a very junior partner in a smaller European mission called Euclid, blasting off in 2019.

But, given a green light and some money, a mission with the "repurposed" telescope could be started in 2020. Of course, Mr. Moore added, "we have no money." Building the telescope can amount to a quarter to a half of the cost of a space astrophysics mission, astronomers said. Dr. Moore estimated that having it already would save the nation $250 million.

It gets better.

Can look for supernovae and exoplanets

The telescope’s short length means its camera could have the wide field of view necessary to inspect large areas of the sky for supernovae. Even bigger advantages come, astronomers say, from the fact that the telescope’s diameter, 94 inches, is twice as big as that contemplated for WFIRST, giving it four times the light-gathering power, from which a whole host of savings cascade. Instead of requiring an expensive launch to a solar orbit, the telescope can operate in geosynchronous Earth orbit, complete its survey of the sky four times faster, and download data to the Earth faster.

Equipped with a coronagraph to look for exoplanets — another of WFIRST’s goals — the spooky Hubble could see planets down to the size of Jupiter around other stars.

"It’s a really good prescription," Dr. Grunsfeld concluded, adding that if he had sent somebody out to design a telescope from scratch for the dark energy task, he would have been happy with this result.

Among other things, Dr. Grunsfeld said, adopting this telescope "means people can’t sit around for three years figuring out designs."

If it sounds almost too good to true, it might be, cautioned Dr. Riess, who noted that a thorough estimate of the new mission’s costs had not been done yet.

But still, how often do you get offered a used piece of equipment the size of the Hubble Space Telescope? "When someone hands you a hand-me-down like that you have to be excited," Dr. Riess said. "They’re not sitting around at Wal-Mart."

Dr. Spergel said he was very hopeful. "It's not a done deal, but it's plausible," he said. As a space mission veteran, he said he was used to having to downsize projects when they became too ambitious or expensive. He said wistfully, "I’ve never been involved with an upscope and a decrease in cost."

Dr. Grunsfeld said the repurposing of the telescope for dark energy came at a personal cost. He had long dreamed that the Hubble, which he and the other astronaut-servicing teams had said goodbye to forever in 2009, might be visited again and upgraded one more time to do the dark energy work. That dream, he admitted, was now dead.

"If for half the cost you could turn this into a telescope, why would you do that?" he said.

This story, "," originally appears in The New York Times.