Physicists investigating the makeup of the universe are closing in on the Higgs boson, an elusive particle thought to have been key to turning debris from the big bang into stars, planets and finally life, scientists said Tuesday.

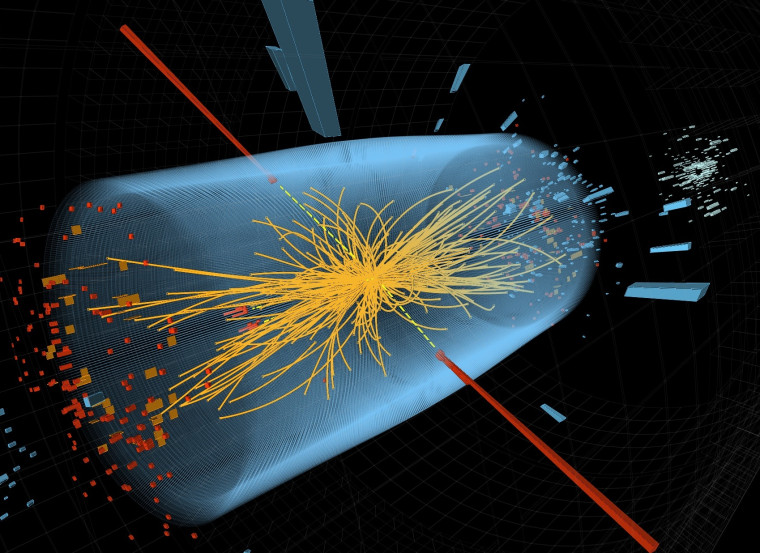

Researchers at Europe's CERN particle physics center are using the Large Hadron Collider, the world's biggest particle accelerator, to try to prove that the mystery particle really exists.

Poring over huge volumes of data, CERN physicists are confident they are now closer to achieving that aim, according to two scientists with links to two key research teams at facility, located on the French-Swiss border.

"They are getting quite fired up," one scientist outside CERN but with links to the experiment told Reuters on condition of anonymity.

Strong signs of the Higgs were being seen in the same energy range where it was tentatively spotted last year, the scientists said, even though the particle is so short-lived that it can only be detected by the traces it leaves.

The quest for the obscure but scientifically crucial Higgs boson is being conducted by harnessing the LHC's high-energy accelerator, which is located on the edge of Geneva, to replicate the energies that were present in the universe just after the big bang, the process that scientists believe brought the known universe into being.

The Higgs is named after British physicist Peter Higgs, who in 1964 first came up with a detailed idea of what it might be. The particle is the last major missing piece in the so-called Standard Model, which describes how the universe works at the level of elementary particles.

Its formal discovery, once it is endorsed by the world scientific community, would almost certainly ensure a Nobel prize for Higgs, now 83 and retired, and perhaps for at least one other European physicist and one American.

The scientists spoke of their CERN colleagues' progress after research chiefs at the facility decreed a cutoff last weekend in the processing of all data related to the search for the particle ahead of a major physics conference, the International Conference on High Energy Physics or ICHEP, which is scueduled in Melbourne next month.

There has been widespread speculation that a major announcement on the Higgs, based on careful analysis of the most interesting of over 300 trillion proton collisions in the LHC so far this year, may be made at that gathering.

But there was no confirmation from CERN itself that it was close to announcing it had discovered the particle and its linked energy field, thought to have given mass to matter and shape to the universe 13.7 billion years ago.

Researchers on the collider's separate ATLAS and CMS detectors have been "blinded" — that is, cut off from findings from the rival team and even from different groups inside their own.

CERN spokesman James Gillies said the center would want to make any important announcement, once there was something to say, in Geneva. "As for what ATLAS and CMS may or may not have in the 2012 data, that's only known to a few people in each experiment right now," he added.

"Blinding" is used in science to ensure that different groups working on identical experiments but with different if similar equipment do not influence the outcome of each other's research.

If they then come to the same conclusion, they can safely be seen to have independently validated each other's results, clearing the way to actually claiming a discovery.

In December 2011, after some 16 months of collisions at lower energy levels than this year, both teams joined at CERN to say they had separately seen "tantalizing glimpses" of the Higgs but needed more time to be sure if it was really there.

Data still coming in after last weekend's analysis cut-off will be processed later in the summer. Physicists say that more than half of the collisions produce nothing of scientific value, and the record of their tracks are automatically dumped.