With their elderly parents seated across the octagonal oak table, Donna and Jim Parker were back in the kitchen they knew so well — the hutch along one wall crammed with plates, bells and salt-and-pepper shakers picked up during family trips; at the table's corner, the spindly wooden high chair where a 7-year-old Jim had tearfully confessed to setting a neighbor's woods ablaze.

It was Christmastime, but this was no holiday gathering. Now, it was the parents who were in deep trouble, and this was an intervention.

For the past year, Charles and Miriam Parker, both 81, had been in the thrall of an international sweepstakes scam. The retired educators, with a half-dozen college degrees between them, had lost tens of thousands of dollars.

But money wasn't just leaving the Parker house. Strangely, large sums were now coming in, too.

Their four children were worried, but had been powerless to open their parents' eyes. Maybe, Donna thought, they'd listen to people with badges.

And so, joining them at the family table that late-December day in 2005 were Special Agent Joan Fleming of the FBI and David Evers, an investigator from the North Carolina attorney general's telemarketing fraud unit.

The home was littered with sweepstakes mailers and "claim" forms, the cupboards bare of just about everything but canned soup, bread and crackers. Charles Parker acknowledged that he'd lost a lot of money, but expressed confidence that he and his wife would eventually succeed if they just kept "investing."

Evers and Fleming showed the couple a video of other elderly scam victims, then played a taped interview of a former con man describing how he operated. Charles was alarmed by what he was seeing and hearing, but his wife seemed to be barely paying attention.

With the couple's permission, Evers installed a "mooch line" on the kitchen phone so they could capture incoming calls. The Parkers pledged their cooperation.

After gathering up some of the mailings for evidence, the officers left, encouraged by what seemed a few hours well spent.

But in the coming months and years, things would only get worse for the Parker family — much worse.

Not naive

The Parkers were hardly unsophisticated people, the type to be easily fooled.

Born in 1924, Charles Alexander Parker and Miriam Wilkinson were high school sweethearts back in Pitman, N.J. After Charles served in the Navy in World War II, they married and embarked on a life of learning and teaching.

Charles earned a doctorate in speech communications, and Miriam received a pair of master's degrees, one in special education. Along the way, Miriam gave birth to four children: Donna, Jim, Linda and Carole.

After other teaching stints, Charles Parker took a position in the English department at North Carolina State in Raleigh, from which he would eventually retire. In 1966, the couple built a split-level home, later converting the garage into a classroom for Miriam's special-needs pupils.

Through hard work and thrift, the Parkers were able to send all four children to college and pay off their home. Between their savings and Charles' pension, they were looking at a comfortable retirement.

Then the conman entered their lives.

Older Americans lose $2.9 billion a year to fraud, according to a study last year by the National Committee for the Prevention of Elder Abuse and the Center for Gerontology at Virginia Tech. Most victims are between 80 and 89, and most are women.

Using the latest technologies, "these criminals need not defraud their victims face-to-face," David Kirkman and Virginia H. Templeton wrote in a 2007 article for the journal Alzheimer's Care Today. From far away, "they can identify vulnerable seniors, contact them, and induce them to part with their savings."

A slowing down of brain function comes with normal aging, they noted. The elderly are susceptible to errors in judgment, particularly in situations where a snap decision is required — such as during a telemarketing call.

"Experience teaches us that those with mild dementia tend to be the most vulnerable," wrote Kirkman, an assistant attorney general in North Carolina, and Templeton, a gerontologist.

The Mayo Clinic defines "mild cognitive impairment" as an "intermediate stage between the expected cognitive decline of normal aging and the more pronounced decline of dementia."

The basis for a diagnosis in many cases: falling victim to repeated scams.

Series of calls

No one can say exactly how the trouble began in the Parkers' case.

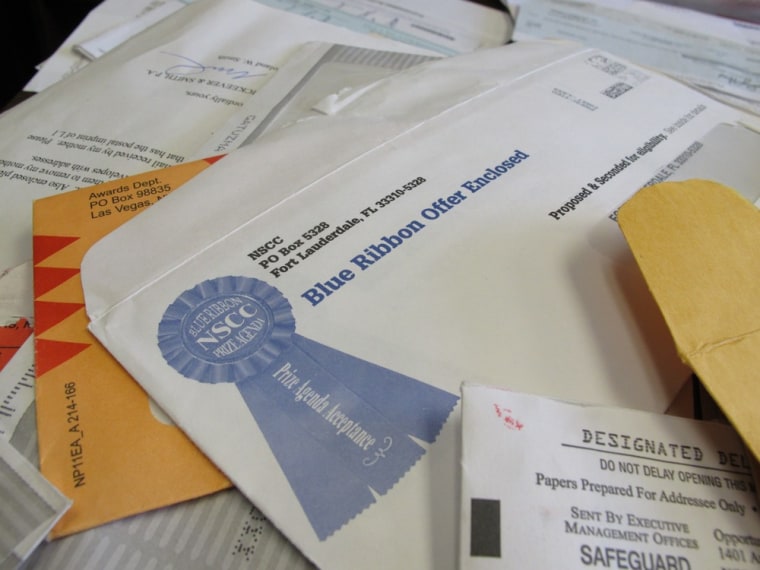

They might have made a small donation to some charity or responded to a sweepstakes letter they got in the mail. Somehow, the couple ended up on what people in the industry call the "sucker list."

Then the scammers proceeded to "reload" them.

You've won this multimillion-dollar lottery, they'd say. All you need to do is send us money to cover taxes, and we'll send you your prize.

So on Dec. 8, 2004, Miriam Parker — then 80 — drove herself to the Wal-Mart down the road to send a MoneyGram to Montreal, Quebec.

Isolation from absent children is often a hallmark in cases like this. But that wasn't so with the Parkers. Sure, Jim had settled in Ohio, and Carole was living in Florida. But Linda and Donna were both just down the road in Cary.

A busy real estate agent and teacher, Donna — the eldest — popped in as often as she could. But she'd always appreciated her parents for not trying to tell her and her siblings how to live their lives, and she did her best to return the courtesy.

In her parents' living room is a plaque that reads, "Mom's 10 Commandments for a Happy Household." No. 6: "If it rings, answer it."

And so, over a series of calls, Howard Clark — a man with a warm voice who called her "dear" and "sweetheart" — had learned enough personal information about Miriam to convince her that he was the family's ticket to riches.

Other MoneyGrams followed. Then, on Jan. 12, 2005, Miriam sent a Federal Express package to a "Mr. Stewart" on Papineau Street in Montreal. Inside, as instructed, was a magazine with $12,550 in cash sandwiched between its pages.

By May 2005, the Parkers had blown through their savings. They had tapped into their home equity line and had maxed out several credit cards. They were running out of things to give.

Unwittingly, their children had contributed to the problem. When Miriam asked Donna for a $7,000 loan, the daughter thought little of it.

Through most of their marriage, Charles Parker had taken care of the couple's finances. But in 1989, shortly after his retirement, he suffered a heart attack. That was followed by colon cancer. As her husband's health declined, Miriam stepped to the fore.

Faced with mounting debt — and clinging to assurances that a big payday was coming — she was determined to right their financial ship.

That's when she became a "money mule."

Family intervention

Howard told Miriam that she'd been "hired" by the Canadian sweepstakes company.

On May 5, 2005, a package from Bloomingdale, N.J., containing $8,275 in cash arrived at the Parkers' home. Others followed and in about a week, Miriam Parker would receive and repackage $60,000 in cash for delivery to Mr. Stewart.

Sometimes, there would be two stacks of bills tucked into magazines. The smaller pile was Miriam Parker's "commission."

Howard said she wasn't to tell her children about their dealings. But the kids had already become alarmed by changes in their mother's behavior.

During visits, Jim noticed that she would race him to the phone, then prevent him from listening to the conversations.

And then there was the need for loans. When Donna asked what for, her parents were evasive.

When the children finally persuaded their mother to get a credit report, the news was jaw-dropping. Their thrifty parents were nearly $200,000 in debt.

Miriam Parker insisted that their ship was about to come in, and that she would soon repay the loans. So Donna gave her a deadline.

In an email to the other siblings, she explained: "I told her that if the money was not there by Wednesday, July 6, the family would be forced to do things we do not look forward to."

The money, of course, did not come. It was time to get authorities involved.

Donna went to the state Attorney General's Elder Fraud Unit. Around that same time, she received a call from the FBI — her parents had popped up on their radar. It became apparent to authorities that the Parkers weren't truly willing participants in the scam. So they staged the December family intervention.

Donna allowed herself to hope that the people who'd ripped off her parents would be caught — and that they might even get some of their money back.

But a frantic phone call a couple of weeks later dashed those hopes.

"They're going to turn the gas off," her mother told her on a day with temperatures forecast to plunge into the 20s.

Eventually, the children were having to buy their parents' groceries.

Attorneys Donna contacted could offer no help — the elder Parkers hadn't been deemed incompetent, and it was their money.

In April 2006, Jim Parker and his wife Susan came to town for Donna's wedding. They were sitting in his parents' kitchen when the doorbell rang.

The FedEx driver handed Jim a crinkly envelope. He knew without opening it what was inside and turned it over to Kirkman, manager of the Elder Fraud Prevention Project in the AG's office.

When authorities opened the envelope, they found an old issue of Martha Stewart Living magazine. It contained $5,725 in cash from a Visalia, Calif., widow.

Kirkman called a contact at Federal Express, who ordered a stop on deliveries and pickups at the Parker home.

But the crooks just switched to United Parcel Service.

And now, in addition to money, they were delivering and picking up car tires and custom rims, and laptop computers worth thousands of dollars — all purchased by other elderly victims.

That's when state and federal authorities reached out to their counterparts north of the border.

Credit union

On Aug. 2, 2006, officers of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Surete du Quebec paid a visit to Dave Stewart.

The Jamaican native acknowledged accepting numerous packages from the American lady on behalf of a man whom he knew as "Roger." Stewart said he was paid $100 per package.

Professing ignorance of any illegal activity, Stewart agreed to cooperate.

Howard, meanwhile, gave Miriam a new address to which she should forward items.

On Aug. 17, 2006, laptops valued at more than $7,200 arrived from Hayward, Calif. She sent them to a "Joseph Reid" in the Montreal borough of Verdun. Parcels kept coming — from Texas and Massachusetts, South Carolina and Washington, Missouri and Maine.

In December 2006, the Parker kids persuaded their parents to grant Donna a limited power of attorney. A month later, she accompanied them to the credit union, where they took out a 30-year, $179,000 mortgage on their home.

Caught red-handed

Miriam Parker had become a cog in Howard Clark's fraud machine. The FBI's Fleming decided to turn the tables on him.

On April 3, 2007, Miriam phoned him — this time with Fleming recording.

"Howard?"

"Yes, dear," he replied sweetly.

As the conversation went on, Howard grew testy about her failure to send her packages quickly. In one case, he noted, trucks had left a UPS office just before an important package arrived from her. Send everything next-day air, he demanded.

When she asked whether she should go back to her former shipper, Howard cut her off: "No, you can't never go there again."

When she suggested that the person at the store was just trying to save her some money, Howard told her that was not their concern and to do as instructed. "I'm giving you the money to pay for this."

Perhaps sensing he'd been too hard, he changed his tone.

"Not to say that YOU are making the mistake, but maybe they are," he said. "And we can't afford for you OR them to make the mistake."

But this time it was Howard who'd made the mistake.

The FBI determined the pitch calls were coming from Montreal, and Mounties soon had a real name for "Howard Clark" — he was Clayton Atkinson, who had 13 convictions for assault, theft and weapons possession.

On April 13, 2007, officers from the RCMP raided Atkinson's apartment and caught him with the "pitch phone" in his hand.

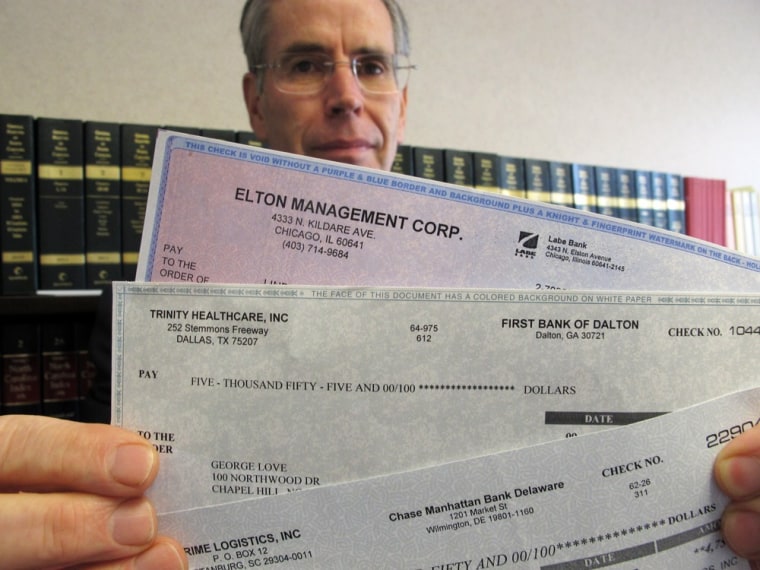

In Raleigh, a federal grand jury handed up a 35-count indictment against Atkinson and two co-defendants — Dave Stewart and Jamaal McKenzie, aka "Joseph Reid." The three were charged with one count each of conspiracy and interstate transportation of stolen property, seven counts of wire fraud and 26 counts of mail fraud.

Mentally incompetent

Even then, the trouble wasn't finished for the Parkers.

A Western Union office called Donna to say her parents had been in a couple of times in one day to wire money to "relatives" in Jamaica. They were clearly a marked couple.

Donna suggested it was time they let her take over their affairs.

"I am NOT mentally incompetent," her father protested.

But in May 2008, she filed a petition, and the court appointed local attorney David T. Watters guardian ad litem. The Parkers were "charming and personable," but hopelessly blind to their predicament, he wrote to the court.

Miriam was his main concern.

"Incredibly, Respondent fails to recognize that the family is the victim of a cruel financial scam," he wrote. "In two conversations, she indicated that she felt that she was working with a better quality of person at this time, and that these people would live up to their promise to provide money to Respondent."

The court appointed Donna Parker guardian of their estate.

Blight on society

The criminal case ground slowly along, and last year Atkinson and Stewart pleaded guilty to one count each of conspiracy and mail fraud. (McKenzie is awaiting trial in Canada on an unrelated assault charge.)

When Atkinson appeared for sentencing at U.S. District Court in Raleigh on March 15, Miriam and Donna Parker were there. Charles Parker had died just a month earlier.

When the time came for victim impact statements, Donna Parker rose. She told Judge Terrence W. Boyle of having to take her parents to court, and of the lingering resentment it had caused.

"Scammers who prey on the elderly," she said, "are a blight on society."

Atkinson said he hoped to one day return to Canada to care for his aging father.

Seizing on this, the judge asked: "Can you imagine if somebody like you was doing this to your family? Could you imagine how shocked and outraged you'd be?"

"I can't sit in front of you and give an excuse for it," Atkinson said.

Boyle sentenced Atkinson to 12½ years in prison, Stewart to 6½. He also ordered them to pay $840,705 in restitution — $84,350 of it to Miriam Parker.

Responding to an interview request, Atkinson, 34, sent The Associated Press a three-page letter, cursing America's "corrupted justice system."

"my life is (expletive) ruined now," his unpunctuated reply said. "you think i care about the parkers"

Smart kids

Miriam Parker kept her home, but she's lost most of her independence. Each month, Donna sends her a debit card with $500 on it, to pay for food and personal expenses. The daughter still screens the mail and pays the other bills.

On a recent day, the two sat at that familiar oak table, a Lazy Susan piled with junk mail between them.

Shuffling envelopes, Miriam told a reporter, "As I look back on it, it was a good bit of stupidity on my part." She said she knows better than to respond to junk mail now.

"I'd better not," she said, casting a glance at her daughter. "Or they would've been on my back, right?"

"Yes, ma'am," Donna replied.

"Which is all right," the mother said. "I have very smart kids."

"We had to be," her daughter said.

More content from msnbc.com and NBC News:

- Four killed after plane hits tree, crashes on take-off in Oregon

- Title IX broke barriers beyond athletics for women

- Juror: Sandusky's lack of emotion at verdicts was 'confirmation'

- Analysis: Number of victims persuaded Sandusky jurors

- Video: Detroit on road to recovery?

- Judge: 13-year-old girl gets lighter sentence if ponytail gets cut off

Follow US News on msnbc.com on and