The problem can be described fairly simply. With hundreds of high-voltage electrical transformers moving thousands of megawatts of power, the failure of any one of them means big headaches for power companies like New Jersey-based PSE&G — and their customers.

So if you could monitor those transformers with a network of sensors — designed to detect small electrical sparks before they get bigger and cause a shutdown — you could improve the reliability of the grid. And you could save millions of dollars in repair costs, and lost business due to power outages.

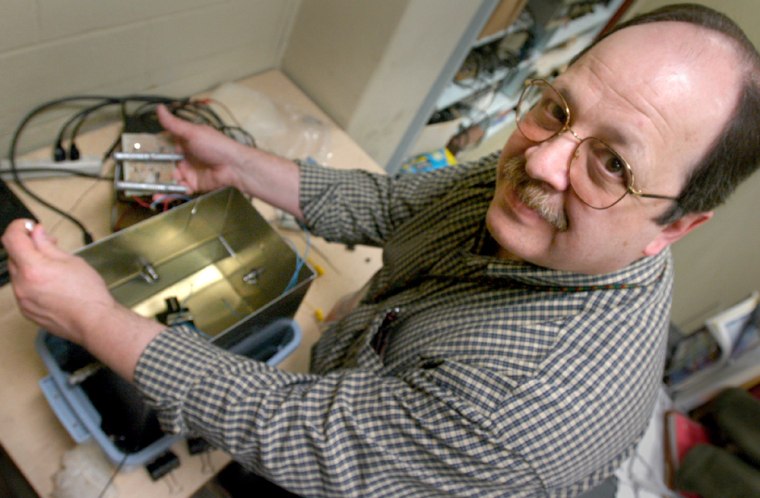

That’s the problem that New Jersey-based inventor Harry Roman and his colleagues are working on at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.

But the solution, it turns out, is not so simple. That’s because traditional electrical sensors are rendered useless by the powerful interference created by huge magnetic fields inside the transformer.

Averting another blackout

“So we’ve gone to a light fiber-optics sensor because it is immune to this kind of electromagnetic radiation,” he said. “We’re converting the vibration that the sound (of a spark) makes on a diaphragm and measuring it with light.”

After four years of research and testing, Roman and PSE&G are hoping these sensors can be installed along various parts of the electrical grid, including thousands of underground splices that could be monitored for early signs of failure.

Sensors like these could some day prevent the kind of massive power outage that crippled a large swath of the U.S. power grid last August, after trees came in contact with a power line managed by an Ohio utility. The outage cascaded through eight states and parts of Canada, causing a blackout that affected 50 million people and cost the economy $6 billion.

Roman says he can think of another 10 applications for the sensors, but he’s reluctant to discuss them until the patent application for the sensor has been submitted.

Seasoned inventor

Roman has made a career of inventing and helping other aspiring inventors, including visits to local classrooms to talk to students. He holds on inventions as diverse as an automated meter reader and a process for speeding up the production of the cancer drug taxol. Until recently the head of the New Jersey Inventors Hall of Fame, he has also counseled others inventors on how to avoid his profession’s pitfalls.

One of the biggest hurdles for individual investors — aside from raising the funds to back their research — is the patent process, says Roman. With application backlogs running two years or more, Congress is considering raising fees by 20 percent to hire more examiners. That added burden will hit small inventors hard, he says.

“A typical patent today can cost $30,000 to successfully move through the process,” said Roman. “That’s tough for a small-business person.”

'The copycats are at work'

And recent changes in patent regulation — requiring publication of a patent application before it’s approved — have made it even tougher for individual inventors to protect their financial interests, said Roman.

“If it takes 24 to 28 months for your patent to move through, the copycats are at work while you’re being reviewed,” he said. “In 1960, the average life of a product was 10 years. Today it’s a year or less if it’s computer-based or a software product."

To overcome the financial risks of going it alone, many inventors, including Roman, team up with large, corporate research labs. In exchange for funding their work, these corporate labs own the patents for inventions developed on company time. But Roman says he expects the role of lone inventor working out of a garage will never go out of style.

“I don’t think you’ll ever see a time when there is not an individual inventor because the passion to invent starts with an individual,” he said. “It does not start with a company.”