More than three-quarters of a million years ago, early humans gathered around a campfire near an ancient lake in what is now Israel, making tools and perhaps cooking food, in the earliest evidence yet found of the use of fire in Europe or Asia.

Researchers have found evidence that these early people hunted and processed meat and used fire at a site called Gesher Benot Ya’aqov in the northern Dead Sea valley.

Developing the ability to use fire “surely led to dramatic changes in their behavior connected with diet, defense and social interaction,” said lead researcher Naama Goren-Inbar of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Occupation of the site has been dated at about 790,000 years ago, according to the research team. Their findings are reported in Friday’s issue of the journal Science.

Hearth and flint

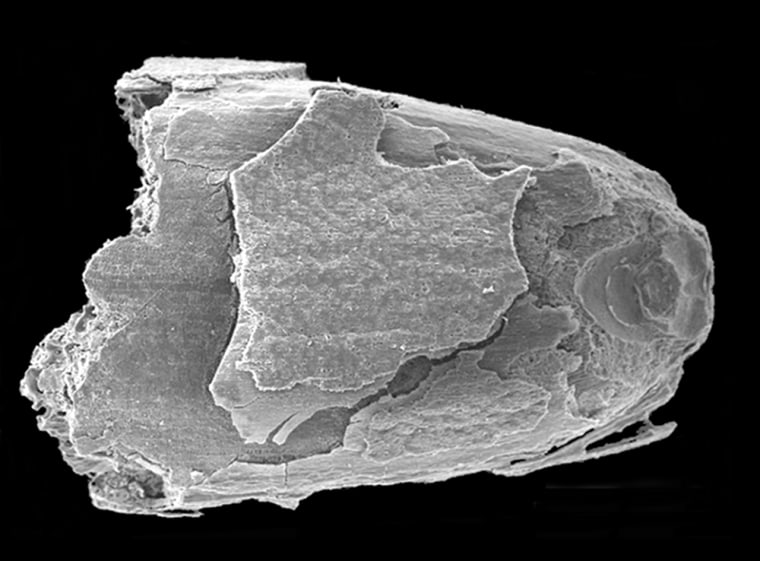

The remains of burned wood indicate the possibility of a hearth, the researchers said, and there were tiny flint pieces, probably chipped off in the process of making tools.

There also is evidence of consumption of meat, including bones with cut marks and breakage patterns indicating the extraction of marrow.

The evidence indicates the early humans ate a variety of animals including horses, deer, rhino, hippo and birds, Goren-Inbar said in an interview via e-mail.

Several types of wood were burned at the site, including willow, poplar, ash and wild olive. There also was evidence of oats, wild grapevine, bedstraw, barley and several types of grass.

The find “enlarges the scope of our understanding of the behavioral patterns of the early humans,” Goren-Inbar said. “It allows us to understand that these hominins were capable of coping with dangers, food, acquire warmth and later on in the history of mankind enabled some very meaningful technological inventions.”

Earlier sites in Africa

The earliest previous sites in Europe and Asia that show evidence of human use of fire have been dated at about 500,000 years ago. Thus, the new finding pushes back the earliest evidence for control of fire by residents of Asia or Europe by more than a quarter-million years.

There are earlier sites associating fire with early humans in Africa, though some researchers believe the evidence at those locations is ambiguous and natural fires cannot be ruled out.

Anthropologist Paola Villa of the University of Colorado, who was not part of the research team, called the new report an important find.

“The evidence presented in this paper is very convincing because it is based on a combination of different kinds of data,” she said. “Supportive evidence for the presence of fireplaces is also provided. The authors have considered all possible alternative explanations,” she said.

“This is an important find that will encourage European archaeologists to take a closer look at their data,” Villa added.

Crossroads of migration

The Israeli site is at a crossroads for movement between Africa, Asia and Europe and use of fire could have helped spur the colonization of the colder climate of Europe, which began about 800,000 years ago.

Still unknown is exactly who these early people were. The paper notes that residents of this site have been assumed to be the now extinct Homo erectus or Homo ergaster, but may also have been an archaic version of modern humans, Homo sapiens.