Eric Fortier used to build airplanes at Boeing, but that was before Sept. 11, 2001. He was laid off soon after in the economic fallout from the terrorist attack. One night, while musing how they would provide for their two special needs children, Fortier and his wife, Tina, figured they'd found their answer while watching television. An infomercial described an easy process for turning a simple invention into a steady revenue stream.

"We knew hard times were coming," Fortier said. "We saw Sept. 11; everybody did."

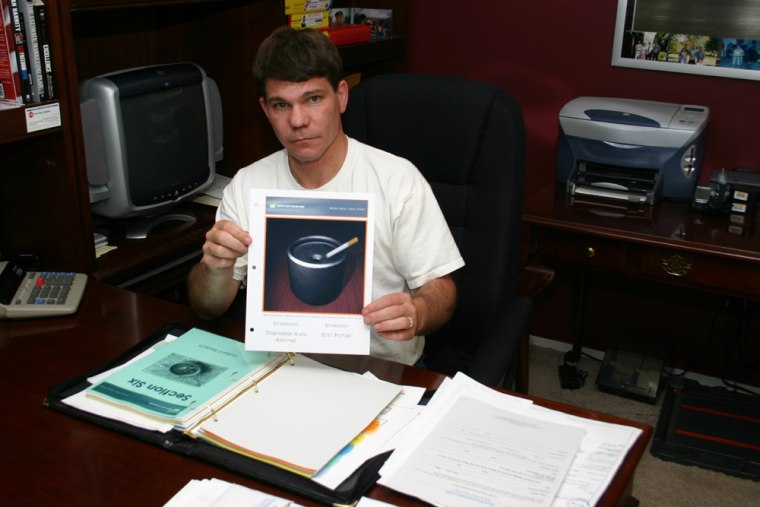

As former smokers, the couple was well aware that fines in Washington state can exceed $1,000 for throwing cigarette butts out of car windows. So they came up with an easy solution -- a disposable butt holder that automatically snuffs out cigarettes. A machinist by trade, Fortier knew his simple device could be cheap to produce in high volume, but he had no capital to get the idea off the ground. He certainly had no idea how to market the device or get it into retail stores.

Enter NewInventions.com. With just a small up-front fee, and an agreement to split the profits, NewInventions.com would take care of all those details.

"We spent a lot of time on the computer. We looked them up in the Better Business Bureau and saw no complaints. That's why we did business with them," Fortier said from his home in Woodinville, Wash. "So we contacted them. They contacted us. We went back and forth for a little while. It was actually quite a while before any money changed hands."

Family and friends pitch in

The firm only asked for $500 at first. A flurry of optimistic letters and phone calls followed, suggesting the invention was a winner. Another $3,000 was sent, gleaned from family and friends turned fellow investors, and back came a business plan. An impressive-looking binder arrived in the mail, complete with an artist's rendering of the product and a market survey. It indicated a potential market size of more than $1 billion for the disposable ash tray.

Then, the firm asked for another $3,000 to begin marketing, and to build a Web site.

Soon after Fortier wrote that check, NewInventions.com fell silent. The promised Web site never materialized. Phone calls and letters weren't returned. A visit to the NewInventions office in Florida by Fortier's brother-in-law revealed the ugly truth: The office was empty, but for a few party balloons left on the floor and a pile of mail inside the door.

"We have big dreams ... but we couldn't afford to lose this kind of money, with the kids and the care they need," Fortier said. "I should have known better. But we got sucked in, like a lot of other people."

Among those other people were John and Patsy Newman, who also gave big bucks to NewInventions.com, hoping their dream would come true. The Florida couple sent $8,900 to the company during a six-month romance, hoping NewInventions.com could promote the special cushion Patsy had invented to help people with spinal injuries. But their story is the same as Fortier's. After writing a series of checks and getting a spiffy business plan, they heard nothing more.

NewInventions.com is currently out of business, says Lee Schierenbeck, an investigator at the Hillsborough County Consumer Protection Agency, where the company was located. About 100 victims gave up to $10,000 each to the company, she said; her office has received 23 complaints.

"This is some people's life savings. Granted, for some of them it's a pipe dream. But it's sad," Schierenbeck said. "There are a lot of angry people out there."

Attempts to contact Web site owner Eugene Ramos, found by searching the Florida Secretary of State's Web site, were unsuccessful. A phone message left at his residence wasn't returned.

The Newmans are now organizing a group of about 20 victims, hoping for recourse through the legal system, but they aren't optimistic.

"We know we're not going to get our money back. But we want to stop this from happening to other people," Patsy Newman said. "We can't believe people still go around doing things like this."

$300 million-a-year industry

In fact, hundreds of firms do it — it's an epidemic, says Ron Riley, himself an inventor and a self-appointed watchdog of so-called invention promotion firms. Two years ago, the U.S. Patent Office estimated that inventors lost $200 million each year. Riley says it's probably more like $300 million now. Despite dogged efforts to inform consumers, a long list of sanctions and courtroom defeats for the firms involved — and even a new federal law passed by Congress in 1999 — the problem just keeps getting worse, Riley says.

"I have shoeboxes full complaints," he says. "There are hundreds of companies doing this. I could add 20 or 30 to my 'caution' list right now."

Riley maintains a consumer information site called InventorEd.org, which he funds with his own money. He regularly crusades on behalf of consumers in an attempt to get refunds, but with mixed results. His site is full of consumer complaints and correspondence with companies. But the critical page on his site is his Caution List, where he cites hundreds of companies that consumers should be wary of when attempting to market their inventions.

The U.S. Patent Office engaged in its own education campaign two years ago in an attempt to draw attention to the problem. Still, consumers can't seem to help but fall for the old ploy, says another watchdog, Gene Quinn. The Syracuse, N.Y., patent attorney maintains an inventor education Web site named IPWatchDog.com. He even pays Google so his site comes up among the invention promotion sites under paid advertisements when a visitor does a search.

He says inventors have just the right mindset to be taken to the cleaners.

Tell them what they want to hear

"What they are doing is they are selling dreams and telling you exactly what you want to hear. Some of these inventions ought not to see the light of day. But they will say, 'This is the greatest thing since sliced bread. Send us $800 so we'll do a patent report.' They've never seen an invention they're going to reject," Quinn said. "You hear people all the time say, 'I took every last dime that I'd saved and paid for this.' It turns my stomach to hear these stories."

Among the more stomach-turning tales involves Virginia Jones, an elderly widow from Graham, N.C., who took out loans from an invention-financing firm to pay for $20,000 worth of worthless services. She and her former husband invented a device that controls smoke emissions from wood stoves after an accident in their home several years ago caused extensive smoke damage. Jones spent more than $10,000 with one firm, and had only a patent to show for it. That company eventually refunded her money, but only after she agreed to a "gag" order not to discuss the case. Meanwhile, a second firm, Invention Publishing and Research, noticed the patent on file at the U.S. Patent Office and pursued Jones, saying it had a better way to promote the product. She fell for this second ploy, too, even though by now she had moved into low-income housing.

"Two or three times they were acting like they were close to getting somebody interested," said Jones' son, Alvarado. "For the money we paid, they got a six-month period to work with. And after that period of time we didn't hear from them. It was like they just disappeared."

Steve Lee, a spokesman for Invention Publishing and Research, said he couldn't comment on Jones' case because it happened in 2001, before he started working for the company. He said 22 percent of inventions submitted are actually licensed, but he could not say how many consumers earned more than they spent signing up with his firm. He said the company regularly shows off inventor's products at more than 50 trade shows around the country each year.

Federal Trade Commission attorney Peter Lambert says inventors often fall for flattery.

"What I tell inventors who call me is, you can never tell the mother of a newborn baby that this wrinkled little ball is not the most beautiful thing you ever saw," he said. But what inventors really need, he said, is honest feedback — not ego stroking, followed by a big bill.

FTC targets some firms

The Federal Trade Commission and various state authorities have taken several sweeping legal actions against invention firms, beginning with a 1994 settlement with Invention Submission Corp., one of the largest firms. In that deal, the firm agreed to pay $1.2 million to redress consumers without admitting to any wrongdoing. The FTC charged that the company made several misrepresentations to consumers while persuading them to pay fees ranging from $395 to $4,890. Other legal actions include:

- The FTC sued American Inventors Corp. in the mid-1990s after the firm made $60 million off 34,000 amateur inventors. It's owner agreed to pay more than $2 million in fines.

- Global Development Services Inc. settled out of court in 1996, after agreeing to pay $1 million in consumer refunds and to give customers a written notice stating that, since its inception in January 1994, not one of its clients has received profits of any kind from an invention as a result of Global's services.

- National Invention Services Inc., an invention promotion firm out of Cranford, N.J., agreed to pay about $750,000 in consumer redress under a proposed settlement announced in July 1998 by the FTC. The case was part of the commission's 1997 Project Mousetrap roundup, which cited a number of companies for bilking $90 million from consumers.

- Universal Consulting Service, also called Continental Ventures Inc., agreed in 2000 to refund more than $240,000 to consumers after it was sued by the Missouri state attorney general.

The rabid growth of such firms and the flurry of legal activity got the attention of Congress in the late 1990s, when lawmakers approved the American Inventor's Protection Act in 1999. The law mandates that the U.S. Patent Office keep a complaint database for consumer reference.

Dismal success rates

It also forces companies that do invention-related business to disclose success rates to consumers. For instance, companies must reveal how many consumers actually made more money than they paid the promotion firm.

Typically, companies reveal this data at the last possible moment, after a consumer has all but signed on the bottom line, experts say. Invention Submission Corp. lists the information on its Web site. From 2001 to 2003, the firms signed deals with 6,480 clients, but only 14 made more money than they paid.

Those results are typical, Lambert said. "I'm not aware of a single company with over 1 percent," he said.

Still, despite all the legal activity and the abysmal success rates, invention promotion firms continue to flood the airwaves with marketing pitches, and still snare eager inventors.

"You can't watch late-night TV anymore without seeing one of these advertisements," Quinn said.

Patent Office faulted

Quinn and others fault the U.S. Patent Office for not taking a more activist role in warning consumers. And in some ways, the patent office serves to legitimize the promotion business, experts say. Because invention promotion firms can procure patents for consumers — albeit usually design patents, which generally aren't worth much — consumers can easily be duped into believing the companies are performing a worthy service. After all, they get a snazzy looking government document to put on the mantle.

"People can in good faith say, 'I can get you a patent,' " Quinn said. "These people are able to use the patent office to prop themselves up." A more diligent patent office would probably reject many of the consumer ideas submitted by invention promotion firms as useless, or lacking novelty, he said.

Riley says the impact of unscrupulous promotion firms goes far beyond the financial losses of victims. Many would-be inventors give up on their ideas, he said, meaning that products that might help people and create new businesses are forever lost.

"All of society is victimized," Riley said.