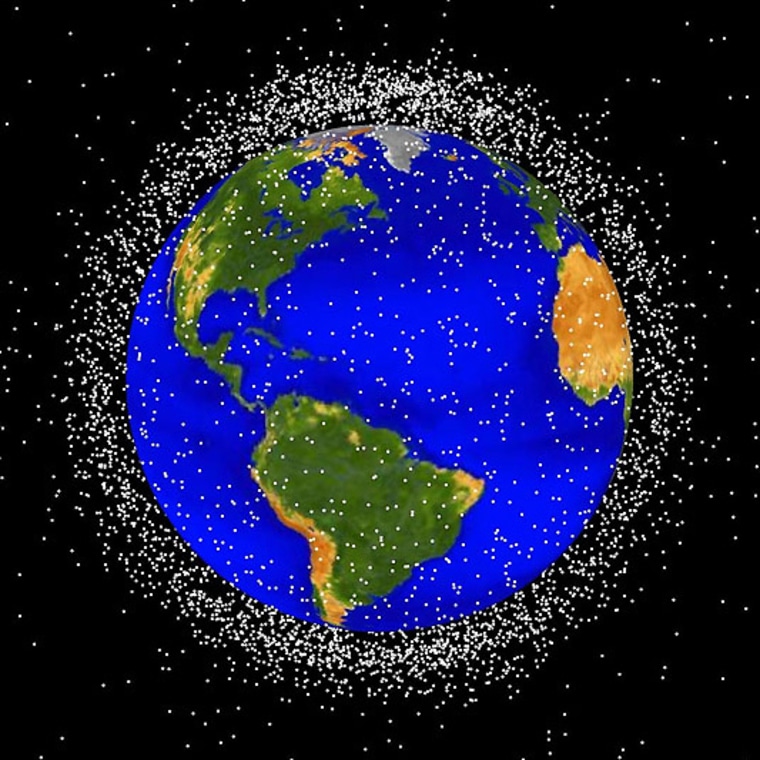

Earth orbit is muddled with human-made hazards from numerous nations in the form of on-duty satellites, deserted spacecraft, leftover fragments of exploded rocket upper stages, chunks of solid rocket motor propellant and even tiny flecks of paint shedding from space hardware.

But that’s not all. Toss in fast-moving separation bolts, lens caps, momentum flywheels, nuclear reactor cores, clamp bands, auxiliary motors, launch vehicle fairings and adapter shrouds. At one point, there was even a toothbrush reportedly zipping through the global space commons.

Some space trash tumbles into Earth’s atmosphere, or is purposely nudged out of orbit to crash into remote stretches of ocean. One problem: Portions of spacecraft and other space hardware, sometimes significant pieces, may survive re-entry and pose a hazard to people and property on the ground.

The point is, after nearly a half-century of satellite launchings, low Earth orbit is no longer the wide-open spaces of days gone by.

Now experts have begun to discuss a surveillance and collision avoidance service — a traffic cop-like tactic to better regulate outer space.

Worrisome factoids

Today there are more than 10,000 objects larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters) that are tracked by U.S. ground surveillance equipment. Of that total, roughly 700 are operating satellites. In the majority, discarded flotsam populates space.

There are also millions of tiny bits of material, including droplets of radioactive coolant that leaked out of poorly plumbed Soviet nuclear-powered spacecraft.

Here are some worrisome factoids:

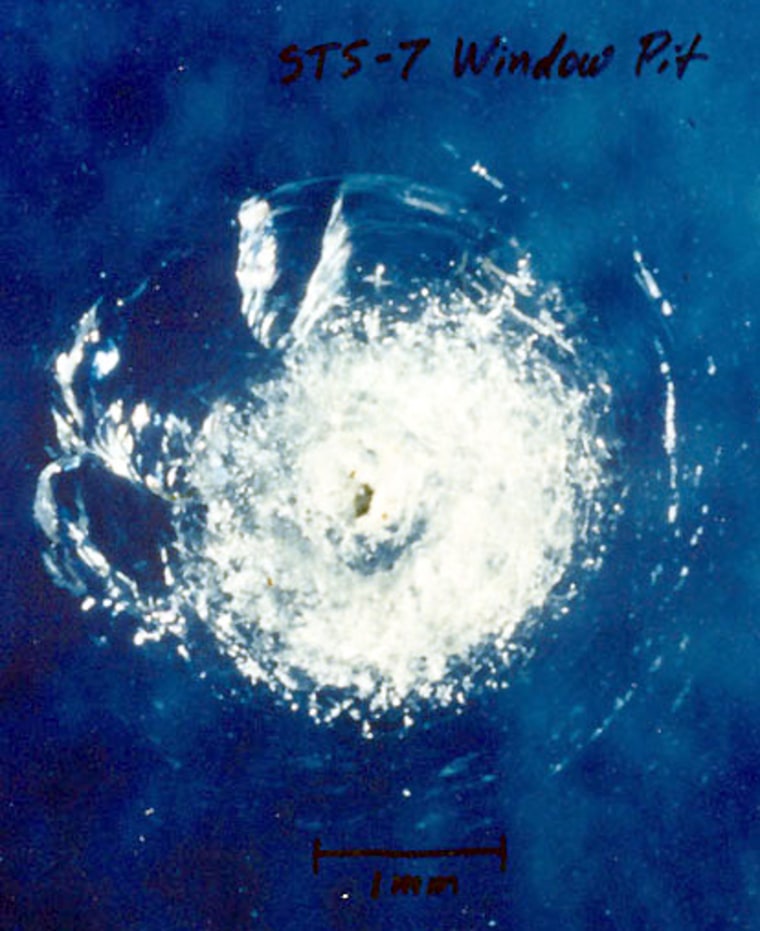

- Throughout its flying years, the space shuttle has moved more than eight times to avoid an oncoming object.

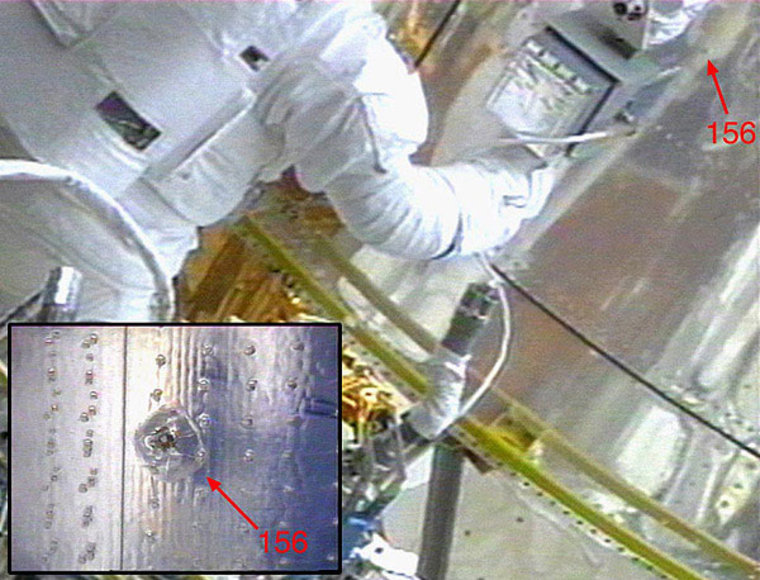

- The international space station has dodged a large tracked object six times since it has been in orbit.

- Operators of a German satellite had to fire onboard thrusters to avoid debris.

- Ground controllers of a satellite were surprised to find that they were sharing the same geosynchronous Earth-orbiting slot with another operator and that the two satellites at times passed unacceptably close.

"These are real events that are happening today," explained William Ailor, principal director of the Center for Orbital and Re-entry Debris Studies at The Aerospace Corp. in El Segundo, Calif. "They are harbingers of things to come as space gets busier."

Ailor said that a major collision of two orbiting objects is predictable. Furthermore, it is inevitable that communications will be disrupted unintentionally, but nonetheless harmfully, by radio frequency interference between satellites, Ailor reported during an April 22-24 meeting on ensuring security in space, sponsored here by the Center for Defense Information.

Weighty issue

The only reported collision of two tracked objects took place on July 24, 1996. The French Cerise satellite was hit by a chunk of Ariane H-10 rocket stage. A boom on the spacecraft was clipped off during the incident, although the craft was later able to continue its mission.

"There were no legal consequences from this event, but it is very likely that the loss of a high-value commercial satellite caused by impact with another operating satellite or by identifiable debris will lead to a lawsuit," Ailor noted.

Dealing with space debris is a weighty issue, even in physical terms, said Lubos Perek, noted space debris analyst and senior scientist emeritus at the Astronomical Institute at the Academy of Sciences in Prague, Czech Republic. From 1975 to 1980, he served as chief of the Outer Space Affairs Division at the U.N. Secretariat in New York.

Perek said at the CDI gathering that the total mass of the debris population is increasing and approaching 5,000 tons.

"The most important problem is that large debris would break up into small pieces in course of time, thus increasing the population of dangerous fragments," Perek said. "It is a question if all that mass can be left in orbit without jeopardizing future space activities."

Fast-talking lawyers

No doubt, future collisions will result in fast-talking lawyers, insurance representatives and government specialists. Rules of the space road and procedures to minimize collisions are likely to be mandated.

"Space traffic control is an idea whose time has come," said Theresa Hitchens, CDI’s vice president. "Some of the best ideas have come out of industry … which tells you there is a serious problem needing to be solved. It isn't often that industry clamors for more regulation!"

Hitchens said there is need to link aspects of securing safe operations in space, "primarily debris mitigation, improved space surveillance and notification policies among operators that can ensure against collisions."

The other concept that deserves more attention and effort, Hitchens added, is that of developing of an "Incidents in Space" agreement, based on the Incidents at Sea and Prevention of Dangerous Military Activities agreements signed by the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War. Doing so might further constrain dangerous activities in space.

"Such agreements, on a bilateral or multilateral basis, could help bolster a space traffic control regime by pledging militaries to abide by the rules and avoid provocative actions in space," Hitchens said.

Minimize growth

"The first priority of a space traffic control system should be to minimize the number of objects requiring traffic control," said space debris consultant Donald Kessler of Asheville, N.C.

Of the 10,000 objects currently cataloged by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, only a few hundred are functioning, operational spacecraft, Kessler said, with the remainder being discarded rocket bodies, abandoned spacecraft and fragments of both.

"An additional 100,000 objects in Earth orbit are not being maintained in a catalog, but are large enough to significantly damage most spacecraft if a collision should occur," Kessler told Space.com via email.

Kessler said that it has been the goal of the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office to come up with cost-effective ways to minimize the growth in orbital debris. At the international level, he continued, that task is coordinated by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, or IADC.

Most members of the IADC, Kessler said, are adopting NASA's recommended policy that spacecraft should not remain in low-Earth orbit for more than 25 years after their operational life, and operational procedures should be required to minimize the possibility of accidental explosions in space.

"However, we are not likely to eliminate all orbital debris, and as spacecraft become larger and more numerous, the only option may be some sort of traffic control system," Kessler advised.

Fundamental problems

Kessler said that there are two fundamental problems with using the U.S. Space Surveillance Network to perform the traffic control function.

"Most of the radars in the network operate at a 70-centimeter wavelength and cannot detect objects much smaller than about 10 centimeters," Kessler said. Secondly, "orbital information on cataloged objects is not routinely maintained with sufficient accuracy to provide effective traffic control for a large number of spacecraft," he said.

In order to accurately predict the position of an object in its orbit, Kessler said that new ways of understanding fluctuations in Earth's atmosphere would have to be developed and additional computer processing would be required.

A potential step toward a space traffic control service was made early this year. The U.S. Congress approved legislation that authorized the U.S. Air Force to initiate a collision avoidance pilot program.

The legislation states that the defense secretary may carry out a pilot program to provide "eligible entities outside the federal government with satellite tracking services using assets owned or controlled by the Department of Defense."

Ailor of The Aerospace Corp. said the services offered will likely be related to satellite collision avoidance, space object identification and the like.

The new legislation allows for the government to be paid for services, but provides no specifics on charges. The U.S. Air Force in Colorado Springs, with the assistance of the government’s federally funded research and development community, is now hard at work to establish this pilot service, he said.

Complex issue

There are many challenges ahead to put in place space traffic management concepts and practices, explains Nicholas Johnson, chief scientist and program manager for orbital debris at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Johnson notes that concepts of space traffic management have been discussed for many years. The result: "little progress to date, due both the complexity of the issue and to a perceived lack of urgency."

"Perhaps the greatest challenge is reaching a consensus on the definition of space traffic management and its objectives. In the simplest terms, space traffic management should promote physical and electromagnetic non-interference among the multitude of operational space systems," Johnson said in a recent paper on the topic provided to Space.com.

But contrary to popular belief, Johnson added, air and ground traffic control concepts and techniques offer few analogies applicable to the space environment.

"The value of a space traffic management system must weigh the historical and legally entrenched concept of the freedom of operation in near-Earth orbit against the potential benefits of a new regulatory regime," Johnson said.

Technical foundation

Johnson cautions against a "rush to regulations."

At present there is the emphasis on the establishment of an international authority to enable monitor or enforce as yet undefined space traffic rules. "Such suggestions are clearly premature. Moreover, they lack the explicit support of the major spacefaring governments of the world," Johnson said.

Most spacefaring nations do not yet exert control over the selection of orbital parameters for new space systems within their own countries, much less in an international context, Johnson concluded. "The prospects for such intrusive space traffic management in the foreseeable future are not bright."

There is need, however, to keep building a strong technical foundation on space debris issues. Without doing this, Johnson added, discussions on space traffic management "would likely prove ineffective."