It was the first day of class, and Chris Costello’s instructions to a group of college students in a science building at the University of Texas-Austin were evoking giggles.

“Imagine you’re a third-grader,” Costello, a teaching assistant, told the class. “What’s something that can fly?”

“Superman!” one student called out. “A bird,” said another. “A fly,” a third shouted.

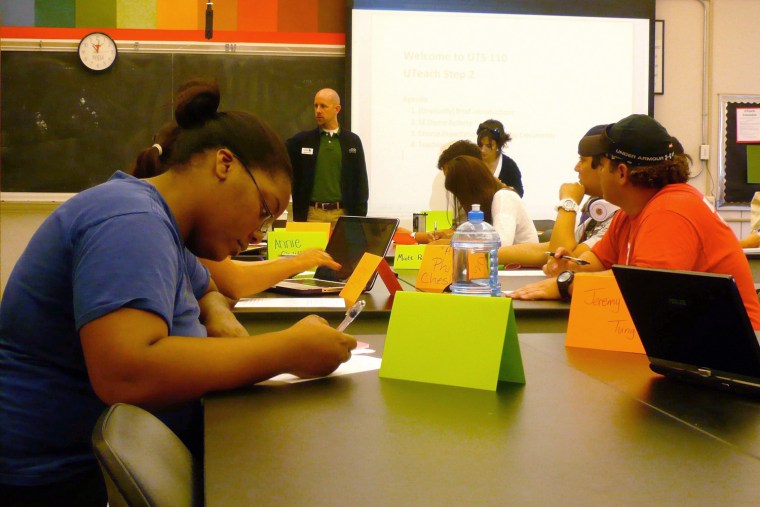

Next, Costello and the course instructor, Shelly Rodriguez, handed out worksheets and brightly colored safety scissors. The students cut out and folded origami “helicopters” and set about throwing them in the air, noting how fast and in which direction they spun.

The lesson was the difference between independent and dependent variables in scientific experiments, a concept that most students in the class — which included chemistry, biology and mechanical-engineering majors — had mastered long ago. But the point was not for these college students to learn something new about variables; it was to help them decide whether they wanted to take their knowledge and pass it on.

“As math and science people, we don’t always see ourselves as teachers, but I hope you’ll keep an open mind,” said Rodriguez, who, like Costello, is a former high school teacher.

Her pitch was the first step in a special program at the University of Texas known as UTeach, an effort to entice talented math and science majors who might otherwise become doctors or engineers to choose teaching instead. It was developed in answer to a growing crisis in American education.

For more than a decade, educators have been sounding an alarm about . They cite grim statistics: Less than a third of eighth-graders on the National Assessment of Student Progress in 2011 and slightly more than a third .

U.S. sinking in science, technology

As a result, the United States is also quickly losing its status as a world leader in science and technology, according to published in 2005 by The National Academies, a nonprofit research group. China, South Korea and France now far outstrip the United States in the percentage of their students graduating with engineering or science degrees (as many as half compared to 15 percent in the U.S.).

This summer, the Obama administration to create a new master teaching corps in science, technology, engineering and math, known as STEM studies. Educators, along with the Obama administration, are also increasingly embracing UTeach, which has spread to 34 universities in 16 states. In the 2005 National Academies report, UTeach was cited as a model that could “transform the quality of our science and mathematics teaching.” Last year, Congress , which includes funding to replicate the UTeach model in other universities.

UTeach was conceived in 1998, when a group of high school teachers and professors at the University of Texas-Austin gathered to discuss what to do about the state of STEM education in local schools. Although occasionally college professors and students would visit local K-12 classrooms to teach a lesson or two, these were “not durable solutions,” recalls Michael Marder, a physics professor at the university.

“There are large (teacher) shortages” in math and science classes in high school, Marder said. “This was clearly a place where the university was well-placed to make changes.”

Mary Ann Rankin, then dean of the university’s College of Natural Sciences, invited the high school teachers to come up with their ideal program for training new math and science teachers — the kind they wished they had before entering the classroom. Professors from both the education school and from the math and science departments then tweaked that curriculum.

Fewer lectures, more student-led work

The result was a series of courses that combine practical teaching experience — before committing to the program, students must teach lessons at a real school to see if they like it — with educational, mathematical and scientific theory.

“We wanted to change it so they weren’t taking generic education classes, but what … you need to teach math and science,” said Mary Walker, a former high school chemistry teacher who helped design the UTeach curriculum.

Traditionally, education colleges have trained math and science teachers, in contrast to the partnership between the math, science and education faculties in the UTeach program. The curriculum is intense, but also relatively condensed, mainly because UTeach students spend more time teaching rather than observing.

The curriculum is heavily focused on inquiry-based teaching, which means fewer lectures and more student-led group work, like the helicopter exercise, and long-term projects.

Administrators say the program has exceeded expectations. Between 2000 and 2011, 702 students graduated from the UT-Austin program (only nine students graduated in the first cohort). The total national enrollment in UTeach programs is now 5,500. And more than 80 percent of alumni are still in the classroom after five years — an impressive number considering that half of teachers nationally leave the profession in that period.

Most importantly, some evidence suggests that UTeach alumni are improving the performance of their students, administrators say.

Newcomers carefully observed

UTeach administrators observe new teachers once they enter the classroom, says Marder, who is now co-director of the program. The program has not yet published the results, though. “We’re working to gather that data,” Walker said.

Schools in Austin, where UTeach alumni make up 20 percent of math and science teachers, have seen big improvements in those subjects, however, which may have something to do with the program’s efforts.

Manor New Tech High School, in a small town just east of Austin, offers more evidence that the program can improve student achievement. The school opened in 2007 with a math and science faculty comprised entirely of UTeach alumni. So far, the school has performed above average on state math and science tests and graduated nearly all of its students, the majority of whom qualify for free- or reduced-price lunches available to low-income students. And 100 percent of those who graduate go on to college, says the principal, Steven Zipkes.

“We have more room to be creative. I like that we’re allowed to do independent work,” said Dharma Casey, a 14-year-old freshman in a biotechnology class taught by UTeach alum Stephanie Hart. It’s a sharp contrast to her middle school experience, she added. “We did a lot of stuff out of the book last year.”

It’s UTeach’s focus on making discovery and creativity integral to the study of math and science that has drawn in many new teachers who might have gone on to more prestigious or better-paid jobs. Janice Trinidad, a teacher at Manor New Tech who has a Ph.D. in physics, says her own education was mostly lecture classes that were “very teacher centered.”

“There are some students in this school who wouldn’t have survived the way I was taught,” she said.

This story, "Education Nation: Program aims to lure next-generation engineers and math whizzes into the classroom," was produced by , a nonprofit, nonpartisan education-news outlet based at Teachers College, Columbia University.