A life spent drifting in the currents, eating whatever food they bump into, was once the presumed fate of most microbes living in the ocean.

But researchers are starting to re-imagine the lives of these tiny microorganisms, which are half the size (or smaller!) of red blood cells. New evidence indicates many ocean microbes are active swimmers, following chemical trails toward food "hotspots."

Ocean microbes are key players in the global carbon cycle, gobbling waste from phytoplankton, the tiny, plantlike organisms that process roughly half the world's oxygen and carbon dioxide through photosynthesis.

"This is where bacteria play a really important role," said John Taylor, an oceanographer at Cambridge University in England. "The rate at which bacteria are recycling that material back into the food web is an important link in understanding how the carbon cycle operates."

In a study appearing Thursday in the journal Science, Taylor and co-author Roman Stocker report that the physical conditions in the ocean influence the rate at which bacteria recycle waste.

For bacteria, moving through the ocean is like swimming through peanut butter, Taylor told OurAmazingPlanet. "Everything happens at such a small scale, they don't feel any of the motion directly, but it does have a direct impact on how efficiently bacteria recycle material," he said.

By far, waste from phytoplankton is the main source of food for bacteria, though Stocker writes in Science that the food hotspots can include anything from sinking fish poop to oil droplets.

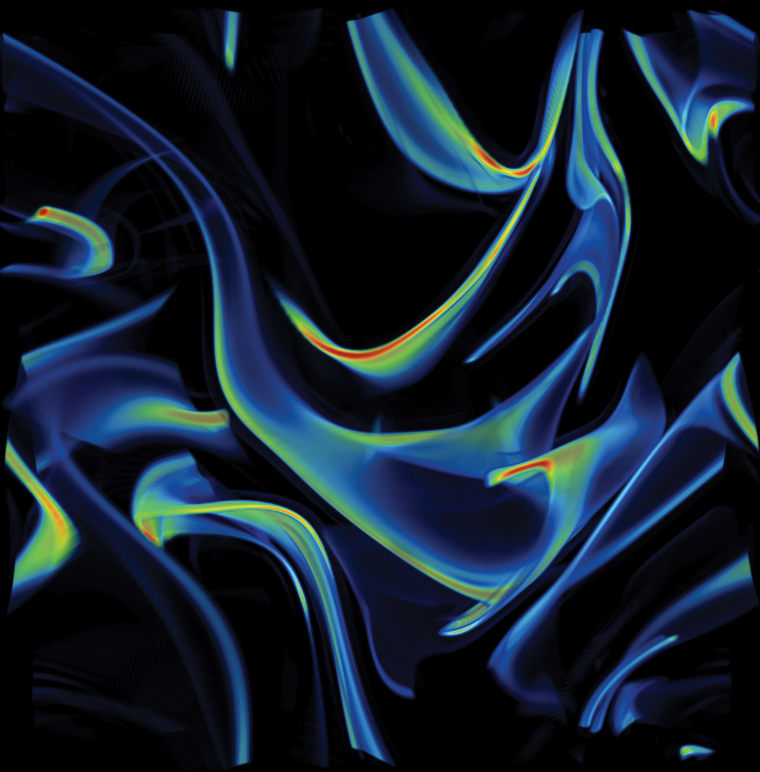

The study found phytoplankton waste enters the ocean in patchy bursts, rather than uniformly as had been thought. Then fluid motion, such as swirling currents, stirs the waste into thin filaments, bringing it closer to bacteria, so they don't have to swim as far for a meal.

The tiny creatures face a trade-off between expending energy on swimming for a possible meal and staying in place for what floats by.

Some bacteria, such as Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis, appear to have evolved better swimming tools, such as a single tail for effective turning with rapid "flicks" of the flagellum, Stocker writes in Science.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct the researcher's name, which is John, not James.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.