For decades scientists have backed the idea of sending robots to collect Martian rocks and return them to Earth, a project that should be possible well before humans crunch their boots into the distant dunes of the Red Planet.

The idea of landing, scooping up, and hauling back to our world specimens from that intriguing globe has long been endorsed as the Holy Grail of precursor missions by Mars exploration planners.

This view was echoed in late September by a summary report from NASA's Mars Program Planning Group (MPPG). Former NASA program manager Orlando Figueroa chaired the blue-ribbon team of MPPG members who were tasked to reformulate the agency's Mars Exploration Program.

Yet other experts question whether robots should do a job that might be better suited for human astronauts. [ The Boldest Mars Missions in History ]

Report findings

An MPPG objective was to explore options and alternatives for creating a meaningful collaboration between science and the human exploration of Mars. More to the point, recent deep cuts in the budget for Mars exploration at NASA necessitated a reconsideration of the Mars robotic exploration program.

Among the summary report observations, the MPPG found that Mars sample return architectures offer a "promising intersection" of objectives between the human spaceflight, space technology and robotic exploration camps.

In a press briefing showcasing the summary report, NASA's John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate, said that sample return represents the best opportunity to find technological synergies between the programs.

"Sending a mission to go to Mars and return a sample looks a lot like sending a crew to Mars and returning them safely. There's a parallelism of ideas there," he said.

Better and cheaper

But is a robotic dig-and-dash Mars initiative a clear, hands-down, need-to-do effort that precedes human explorers strutting across the Martian landscape? And to what degree can rocketing back grab-bag samples help decipher a long-standing, key question: Is there life on Mars?

Another option is to bypass robot surrogates and let astronauts bring back the "Mars goods" themselves. Furthermore, who says the samples must be returned to Earth at all?

"I disagree with the high priority on sample return," said astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch of Washington State University in Pullman.

"Our in-situ (on-the-spot) capabilities are so much better nowadays than, let's say during Viking lander (1970s) times," Schulze-Makuch said. "We could address with an in-situ mission whether microbial life is present on Mars."

Sample return missions are so much more costly, Schulze-Makuch said, "and the only thing that would be advantageous, in my view, is to get an absolute age scale via radioactive dating of Martian rocks," Schulze-Makuch said, "but from an astrobiological viewpoint, (an) in-situ mission would be better and cheaper."

A new NASA goal has stated that from now on any robotic missions should also help support future human missions. This requirement would be satisfied by a robotic mission to ascertain whether life exists on Mars, Schulze-Makuch said.

"One of the greatest questions that needs to be solved before any human mission can be launched is whether there exists Martian life on Mars — both for the protection of the astronauts on Mars and planetary protection considerations the other way around — and this can be best addressed with in-situ robotic missions," Schulze-Makuch said.

Thoughtful collection

"For the foreseeable future, most science done on planetary surfaces will be geological and it should be viewed primarily as a field science enterprise," said Kip Hodges, director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University in Tempe.

Despite the successes of Apollo, the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, and now Curiosity, we really have very little experience with planetary field geology, Hodges said.

"In contrast, we have nearly two centuries of experience with field geology on Earth," Hodges told Space.com. "My perspective is that we should use the lessons we have learned here to inform how to get the most out of our rare opportunities to do planetary field geology on other worlds."

When it comes to sample collection, Hodges said, terrestrial field geologists know better than to sample randomly, unless they have the capacity for many laboratory studies of many samples.

"It seems highly unlikely that sample return from Mars will involve large numbers of samples or large-sized samples," Hodges said, "so thoughtful collection of the best, most scientifically informative samples is critical if the greatest science return is the goal."

Mobility on Mars

For Hodges, collecting the Martian "right stuff" means mobility on the planet is a pre-requisite.

"Whether the collection is done by teleoperated robots or humans on the surface, it is important to get multiple perspectives to establish detailed geologic context before sampling … and one can't do that with a simple lander because you'd be relying too much on luck, in my opinion," he said.

But once you have mobility, the question is whether a human or a robot would be better at getting you the context, Hodges said. Could a human with boots on the surface do that?

"Absolutely — that experiment has already been done here on Earth," he said. Hodges thinks a capable teleoperated robot could do that as well, given sufficient time. However, the geologist remains unconvinced that an autonomous robot would be able to do that anytime soon.

Bottom line

"The question of whether a robotic or human mission would provide better science return is great fodder for argument," Hodges said, moving to a bottom line assessment.

"I don't know if a human mission, given the likely duration of a first mission, could return 'better' samples, but they could collect better samples faster for sure. Is that enough to justify a human mission to Mars ? I think that's the wrong question to ask," Hodges said.

Instead, Hodges said it's whether or not the myriad non-scientific reasons for human travel to Mars will justify such a mission before a robotic sample return mission could be funded. [ Bringing Pieces of Mars to Earth: How NASA Will Do It ]

"If the answer is yes, then, by all means, we could get great samples and including science should be a priority for that human mission. Is there a science driver for human exploration of Mars that can be used as its sole justification? Doubtful. Can it be argued that an unmanned sample return mission is imperative before we send humans? I really don't understand the logic behind that assertion," Hodges concluded.

Site selection

Another consideration is whether a sample return mission to Mars might "flight qualify" a site prior to any human setting foot on the Red Planet, proving that it's safe to send people in its wake.

"Absolutely not. Why should it be — to confirm that the site contains no pathogens? That's ridiculous," responded Robert Zubrin, president of the Mars Society based in Lakewood, Colo.

"The Martian surface can't support microbial life, because it can't support liquid water, and is bathed in ultraviolet," Zubrin told Space.com. "If there is life on Mars, it is underground, in the water table, which the Mars sample return mission won't reach."

To understand the full impact of the "site prequalification" argument, Zubrin said "it must be noted that those who advance it say they want to do a sample return to assure NASA that a given site is free of native life before we send astronauts there. In fact, if Mars sample return or any other probe detected a site with life on Mars, that is exactly where any science-driven program would want to send astronauts."

Zubrin said he views the prequalification argument for the Mars sample return mission as not merely wrong, but absurd. "If that argument is needed to justify Mars sample return, then that mission lacks justification, and should not be entertained," he added.

Alternative robotic missions

Is sample return the best way to pursue the robotic scientific exploration of Mars, within the budget of NASA's Mars exploration program?

"Maybe," Zubrin said. "It is certainly possible to propose alternative robotic mission sets consisting of assortments of orbiters, rovers, aircraft, (and) surface networks … that might produce a greater science return than the Mars sample return mission, much sooner."

Still, Zubrin said that if we are planning human exploration of the Red Planet, human explorers can return hundreds of times the amount of samples, selected far more wisely, from thousands of times the candidate rocks, than a robotic sample return mission.

"However, that said, if the scientific community really believes that a robotic Mars sample is so valuable that it is worth sacrificing all the other kinds of science they could do with the money, then it is imperative that NASA develop the most efficient Mars sample return plan, to allow the sample to be obtained as quickly as possible and with the least possible expenditure of funds that could be used for other types of Mars exploration missions," Zubrin said.

Dementia of bureaucracy

In Zubrin's opinion, the recent MPPG summary report approach to a Mars sample return mission "is probably the unplanned product of the dementia of bureaucracy operating as a social disease, rather than the willful madness of any one individual."

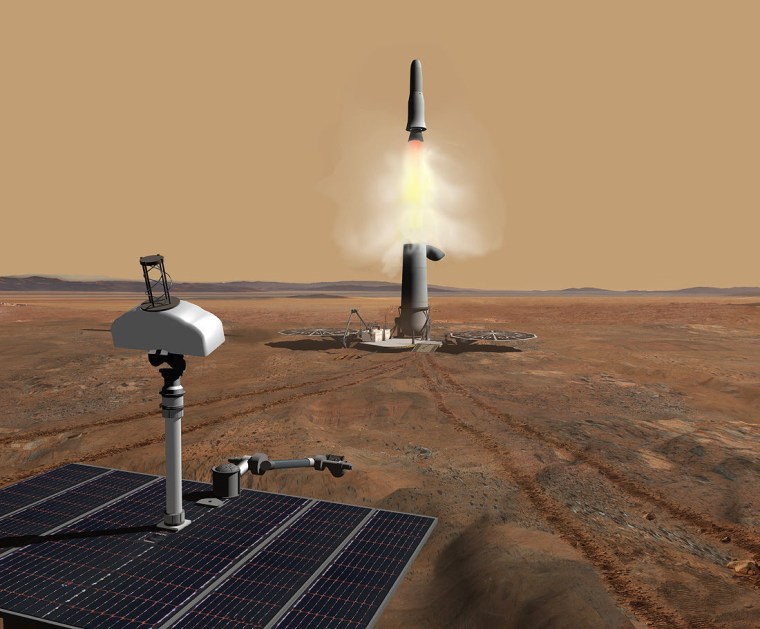

The MPPG summary viewgraphs, Zubrin pointed out, seemingly outline a Mars sample mission conducted in eight parts that include: 1) pre-land a large rover to collect and cache samples; 2) dispatch a Mars ascent vehicle to Mars and perform a surface rendezvous with the rover or its cache of samples; 3) fly the Mars ascent vehicle to orbit the Red Planet and rendezvous with a Solar Electric Propulsion (SEP) spacecraft; 4) fly the SEP spacecraft back to near-Earth interplanetary space; 5) build a Lagrange point space station (Lagrange points are spots in space where the competing gravity of two bodies, such as the sun and Earth, cancels out); 6) fly astronauts to the Lagrange point space station; 7) dispatch astronauts from a Lagrange point space station to take the sample from the SEP spacecraft and return to the Lagrange point space station and; 8) have the astronauts return the sample from the Lagrange point space station to Earth.

The report's sample return plan, Zubrin said, proscribes use of "quadruple rendezvous" for surface rendezvous, Mars orbit rendezvous, deep space rendezvous and Lagrange point rendezvous.

All in all, Zubrin said, the report uses a Mars sample return mission to provide justification for an assortment of current NASA hobbyhorses.

"In short, if we want to get a sample from Mars, we should devise a plan to get a sample from Mars in the simplest, cheapest, fastest and most direct fashion possible, and not let the mission be made into a Christmas tree on which to hang all the ornaments in the bureaucracy's wish box of useless and costly multi-decade delays," Zubrin concluded.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of last year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for Space.com since 1999.